If you go to Ashdod or to the Moroccan neighborhoods of Be’er Sheva, Netanya, Lod or Kiryat Gat, you can still hear Jews there – part of an estimated one million Israelis of Moroccan origin – saying “Allah (Elohim) yensser sidna” (May God grant victory to our king), “Allah yebarek f ‘omer sidna” (May God bless the life of our king) whenever King Mohammed VI’s name comes up. Some still say it for his father, King Hassan II, and even for Mohammed V, whom they never personally met.

Families who left Morocco in the 1950s, 60s and 70s still keep portraits of Moroccan kings hanging in their living rooms, sometimes alongside framed photos of their grandparents in the mellah. At Mimouna celebrations, at hiloula gatherings around rabbinic saints or even at simple family dinners, you will hear prayers for “Sidna” (our king) the same way their ancestors did in Fez, Meknes, Essaouira, Marrakesh and Tétouan.

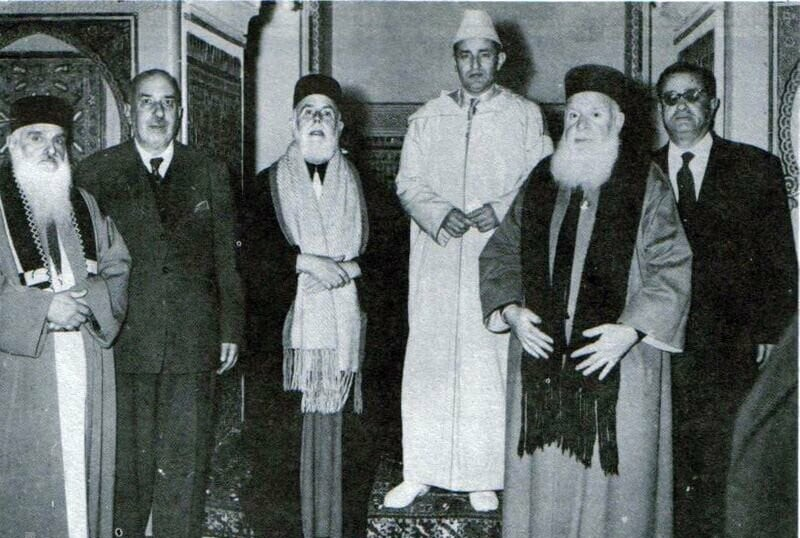

5 View gallery

King Mohammed V returning from exile in November 1955, accompanied by the three rabbis of Meknès

(Credit: Center for Judeo-Moroccan Culture in Brussels)

There are parks and streets in Israel named after King Hassan II, and older Moroccan Jews still speak about him with a softness reserved only for their own fathers. How can this be explained? Why does a Jewish tradition – rooted in the Torah, shaped by centuries of diaspora and marked by both hardship and privilege – still carry a deep, almost instinctive reverence for Moroccan kings?

The answer begins far before Morocco, in the religious foundations of Judaism itself. Kingship in Judaism is not merely tolerated; it is sanctified. The Torah explicitly provides a framework for appointing a king: “When you come to the land… you shall set a king over you” (Deuteronomy 17:14-15). Jewish monarchy is governed by strict ethics: the king must write his own Torah scroll, read it all his life, restrain arrogance and obey divine law. Figures like King David, King Solomon and King Hezekiah occupy not only political space but spiritual authority.

Jewish tradition teaches to respect lawful authority – “dina de-malchuta dina” (the law of the kingdom is law). This means Jews must respect the authority of the king or ruler of the land they live in, even if he is not Jewish. The Jewish blessing for leaders – “HaNoten Teshua LaMelachim” (He who grants salvation to kings) – is still recited.

Even in modern Hebrew culture, the concept of a king retains emotional resonance. Israeli Jews jokingly refer to strong leaders as “HaMelekh,” and some still affectionately call Netanyahu “King Bibi,” reflecting a cultural comfort with centralized, paternal authority rooted in ancient memory. These patterns matter because they shape the emotional and symbolic vocabulary Jewish communities brought with them wherever they lived – including Morocco.

A young king quietly protected his people

When Jews arrived in Morocco nearly two millennia ago, they entered a system where sovereignty was personal. The king – first as sultan, then as monarch – was not an abstract figure but “Mawlānā,” the guardian of religious minorities under Islamic law. Moroccan Jews experienced fluctuations across dynasties, with periods of heavy taxation or restricted movement, but they also rose to prominence as diplomats, treasurers, physicians and advisers.

The Jewish merchants of the “Tujjar as-Sultan” acted as royal commercial agents, while families like the Corcos, the Benattar, the Toledano and the Pallache served as intermediaries between Morocco and Europe. Judah Pallache, for example, was Morocco’s ambassador in Amsterdam in the 17th century, while Shmuel Benwaish and others served as emissaries for the Alaouite sultans.

In Fez and Meknes, Jewish financiers like the Sasportas and the Ibn Attar families held influence within the court. This pattern – Jews respected by the king, protected by the king and integrated into the royal project – carved a deep psychological structure: reverence was repaid with loyalty, and loyalty with protection.

This relationship crystallized during the Alaouite era, especially under Sultan Mohammed V. In 1940-42, Morocco was a French protectorate under the pro-Nazi Vichy regime. Around 250,000 Jews lived in Morocco – roughly 10% of the population. When the Vichy regime took control of French North Africa in 1940, it attempted to impose its full antisemitic program on Morocco, confident that a young sultan – barely in his early thirties and technically a “protégé” of Paris – could be pressured, manipulated or sidelined.

French officials believed he would sign whatever decrees they placed before him, and that the protectorate’s hierarchy would function as it always had: France decides, the sultan ceremonially agrees and Jews suffer the consequences. But the French miscalculated. The young Mohammed V understood both his symbolic authority and the sacred bond linking him to all subjects under his protection, including Jews. He recognized that in a traditional monarchy, moral gestures often had more power than administrative signatures, and he used this space with remarkable precision.

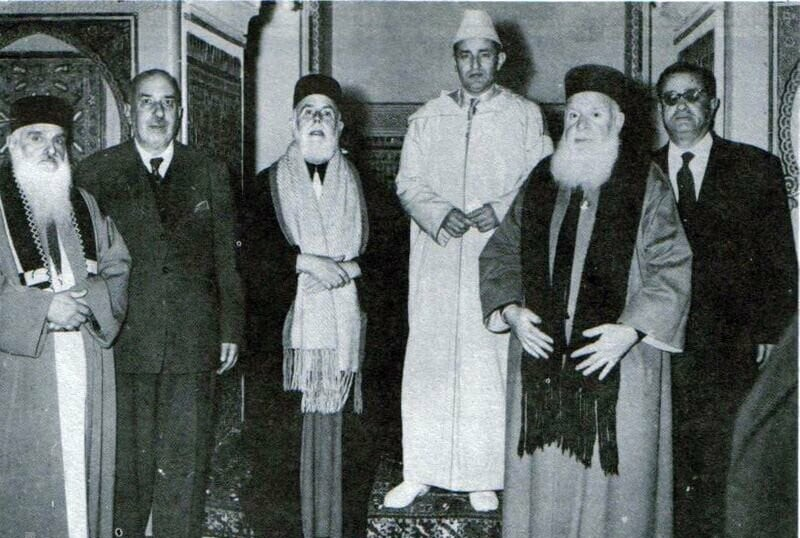

5 View gallery

Jewish rabbis and notable community leaders received by King Mohammed V in Meknès in November 1955

(Credit: DAFINA)

The Vichy authorities expected compliance with the “Statut des Juifs,” the same racist legal framework that had already stripped Jews of their professions, rights and dignity in metropolitan France. They tried to extend these measures into Morocco – dismissing Jewish civil servants, restricting Jewish students and preparing to classify the population by race. Yet in Morocco, the sultan’s moral stance became legendary.

When French officials pressed him to identify the Jews and apply racial laws, Mohammed V reportedly answered, “There are no Jews in Morocco. There are only Moroccan subjects.” It was not just a sentence; it was a refusal to surrender his sovereignty, even symbolic sovereignty, to an occupying ideology. Jewish testimonies, Moroccan memories and international accounts all preserve this line because it collapsed Vichy’s racial logic in a single breath.

“I do not approve of the new antisemitic laws, and I refuse to associate myself with a measure I disagree with,” he told the French government officials. “I reiterate as I did in the past that the Jews are under my protection, and I reject any distinction that should be made amongst my people.”

More importantly, Mohammed V blocked the most dangerous steps of the Nazi process. In Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, Jewish communities endured harsher restrictions and, at times, forced labor under German or Italian supervision. In Morocco, Vichy established labor camps such as Berguent (Bou Arfa), Ain Chock, Djelfa and others along the trans-Saharan railway – camps where hundreds of Jewish refugees and political prisoners suffered under brutal conditions between 1941 and 1943.

These were not extermination camps, but the forced labor, starvation and disease claimed lives. Crucially, the Jews sent there were overwhelmingly European refugees, foreign nationals or political prisoners – not Moroccan Jews living under the sultan’s authority. Inside Morocco itself, not a single Jew embedded in the traditional Moroccan communal system was deported to Nazi death camps, and the yellow star – one of the most visible tools of humiliation – was never imposed. Mohammed V refused to allow it to be worn in Morocco, asserting in both subtle and overt ways that Jewish visibility was not a mark of shame but of citizenship.

He also deployed ceremonial power – often underestimated by Western officials but deeply understood in Moroccan culture. During a period when Vichy sought to isolate and diminish the Jewish community, the sultan invited rabbis, community leaders and Jewish notables to the Throne Day celebrations and to palace banquets, allowing them to stand beside him in scenes that radiated protection and solidarity. In a hierarchical society where proximity to the sovereign signifies legitimacy, these gestures were unmistakable acts of resistance. It was an anthropological and political message: the Jews remained within the royal fold, and no foreign power – neither colonial nor fascist – could redefine them.

By 1942, when the Allied landings in Operation Torch reached Casablanca, Rabat and other Moroccan cities, the Jewish community remained intact, bruised by discriminatory decrees but spared the machinery of annihilation that had consumed millions elsewhere. This outcome was not accidental. It emerged from a complex dance: a sultan without full executive power, a colonial administration obsessed with control and a moral stance that refused to let the Jews of Morocco be reduced to a racial category.

For Jews, memory is sacred, and Mohammed V’s stance quickly passed into collective mythology – part history, part reverence, fully gratitude. In Israel today, Moroccan Jews still speak of him with a tone usually reserved for biblical figures or great rabbis, because deep inside community memory is the knowledge that while Europe was burning, their king, young and theoretically powerless, stood between them and catastrophe with nothing but moral authority and an unshakable sense of duty.

Hassan II deepened Morocco’s Jewish royal bond

King Hassan II inherited that legacy and expanded it into diplomacy and identity. He cultivated a unique relationship with Moroccan Jews at home and abroad. His well-known engagement with American and French Jewish leaders reflected both political strategy and genuine belief. As one widely-circulated saying attributed to him beautifully puts it, “When a Jew emigrates, Morocco loses a citizen, but it gains an ambassador.” The phrase captures the essence of how Hassan II viewed the Moroccan Jewish diaspora: not as a community that had left, but as one that continued to carry Morocco’s name, culture and dignity across the world. It expressed a continuum of belonging that survived distance, borders and generations.

5 View gallery

Rabbi Shimon Suissa presenting his respects to King Hassan II during Throne Day ceremonies on March 3, 1996

(Credit: Cecile TREAL / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

And this same worldview appeared in one of his most intimate and emotional encounters with the Moroccan Jewish community in North America – a gathering remembered for both tears and laughter, where he addressed them affectionately as “our subjects” and began with a playful line: “I believe you still understand Arabic.” Standing before them, surrounded by members of the royal family, he offered blessings on the Prophet of Islam and on the Prophet Moses alike, signaling from the outset a shared spiritual lineage and a shared Moroccan identity.

He then recounted, with warmth and humor, his friendship with a Jewish professor in France – “Professor Steeg, thank God I am not his patient, but I have known him for years” – drawing smiles from the audience. From this story, he moved to a deeper message: that in Moroccan tradition, celebrating the holy days of Christians and Jews is part of Muslim duty. He explained how each year he would ask his friend to inform him of the precise night marking the birth or passing of Moses, so that he could pray for him: “Every year I pray a hundred times for the soul of our Prophet Moses. And as I pray for him, I think of every Moroccan Jew across the world. I ask God to bring them happiness, and to one day bring them back to walk in their country and visit the Jewish cemeteries of their ancestors.”

The room grew emotional when he spoke of their origins: “You came to Morocco before the Arabs. Some historians say that when others followed Moses east across the Red Sea, some feared the water and came west to Morocco instead – and thank God they came.” He praised their heritage with striking clarity: “You have a privilege others do not. You know exactly where your fathers and grandfathers are buried. And you also have another gift: Morocco’s Talmudic tradition is the finest in the world. Our rabbis may be strict – yes, a little tough – but all the rabbis of the world come to consult them to understand authentic Hebrew teaching.” He closed with prayers for their protection and a timeless pledge of belonging: “You are our subjects. As our ancestors protected you, and as we protect you today, so will our children and grandchildren after us. You will always be part of us.”

From the outset, King Hassan II used Morocco’s royal prestige as a discreet diplomatic platform. In 1977, King Hassan II hosted secret talks in Morocco between Israel’s Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Egyptian Deputy Prime Minister Hassan Tuhami, and also between Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s and President Anwar Sadat’s advisers; those meetings paved the way for Sadat’s November visit to Jerusalem and – down the road – the 1978 Camp David Accords and the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty. Less than a decade later, in July 1986, he staged a precedent-setting public meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres at his summer palace near Ifrane, weathering Arab backlash to preserve a line of communication.

The same method carried into the Oslo years, when Morocco became both discreet broker and visible convenor. In September 1993, Hassan received Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres in Rabat on a surprise stopover immediately after the Oslo signing at the White House. Later that December, an Israeli delegation led by Jacques Neriah and MK Rafi Edry was received in the King’s grand chamber in Rabat to brief him on early Oslo developments; the King even offered a plane for Mahmoud Abbas to travel to Europe, illustrating his facilitative posture.

5 View gallery

Israel’s Foreign Minister Shimon Peres meeting King Hassan II at the Bouznika Palace during the 1994 Casablanca Conference

(Credit: Gideon Markowiz, Israel Press and Photo Agency (I.P.P.A.) / Dan Hadani Collection, National Library of Israel / CC BY 4.0)

In June 1994, he again welcomed Peres in his capacity as foreign minister, and that October received him at Bouznika on the eve of the Casablanca MENA Economic Summit. The summit, which Hassan personally hosted, gathered Rabin, Peres, the Palestinians and Arab delegations to operationalize the multilateral track, effectively signaling the end of the Arab boycott. The following year, he went further, hosting Peres – still foreign minister – together with PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat in Rabat, issuing a joint communiqué.

Out of this period came low-level ties and reciprocal liaison offices: Morocco opened one in Tel Aviv in 1994, and Israel opened its own in Rabat in 1996. Israeli ministers would continue to shuttle in and out, including Foreign Minister David Levy in 1999 and Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom in 2003. What endured through all these episodes was the classic Moroccan method: wielding the monarchy’s prestige, convening power, strategic ambiguity and a unique Jewish-Moroccan bridge, calibrated for state actors and PLO frameworks while staying clear of militia politics.

Mohammed VI transformed memory into national policy

Today, King Mohammed VI has deepened this legacy in unprecedented ways. He has treated Jews not as a foreign minority to be “tolerated,” but as a constitutive part of what Morocco is. That shows up in concrete policy: the 2011 Constitution explicitly names the Hebraic component as one of the sources that “nurtured and enriched” the Moroccan nation, placing Jewish memory within the official definition of the country rather than at its margins, and it was followed by the formalization of Jewish family law – a global first in the Muslim world.

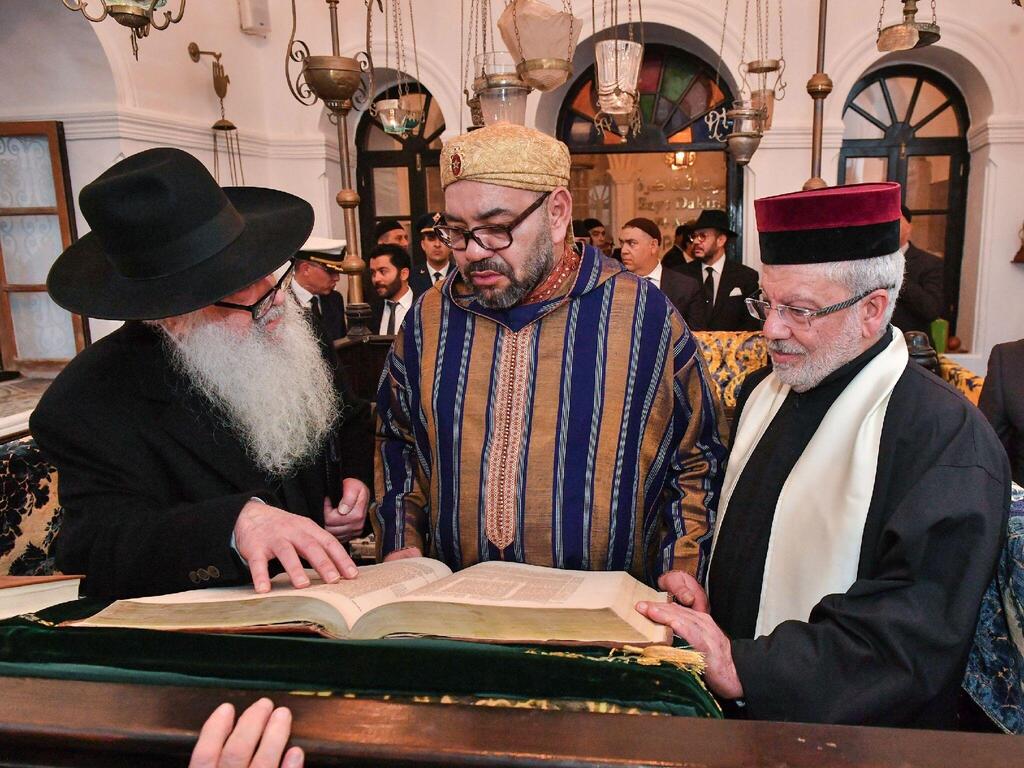

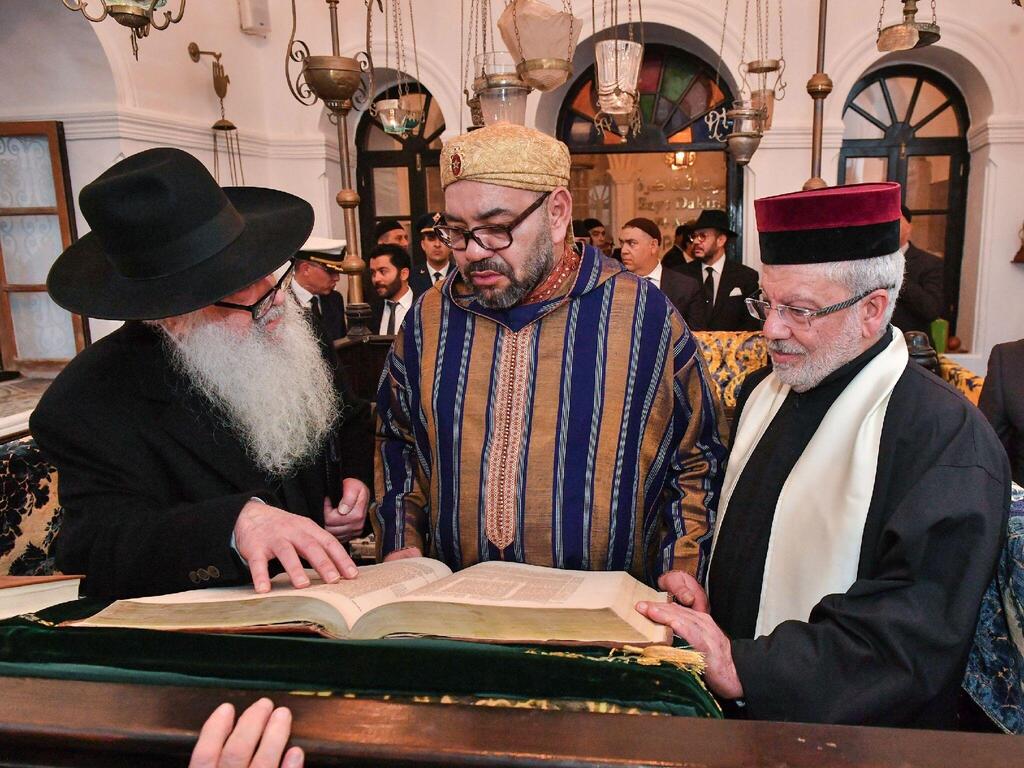

5 View gallery

King Mohammed VI during his visit to Bayt Dakira, a museum dedicated to Jewish-Muslim coexistence in Essaouira, January 15, 2020

(Credit: AFP)

He also ordered large-scale restoration of synagogues, mellahs and cemeteries – most notably the renovation of the Slat Al Fassiyine synagogue in Fez and the restoration of the Jewish museum in Casablanca. He then launched nationwide programs to rehabilitate Jewish burial grounds and houses of worship across dozens of cities and villages, an effort observers often describe as unique in the Arab world.

He pushed the inclusion of Jewish history into public school curricula, a move praised internationally as a serious step against antisemitism rather than a symbolic gesture. His reign has also seen the return of Jewish toponyms and the formal recognition of the Jewish “Toshavim” and “Megorashim” heritage lines. In that sense, his “Jewish policy” is really a national project: he uses the protection and re-centering of Jewish heritage to tell Moroccans that pluralism is not an import, it is their own tradition.

André Azoulay is the intellectual and strategic hinge of this story. A Jewish Moroccan from Essaouira, he has served as senior adviser first to Hassan II and then to Mohammed VI, shaping economic reforms, but also guiding the king’s efforts to preserve Jewish heritage and build bridges with Jewish communities worldwide and with Israel. Azoulay’s work in reviving Essaouira and creating institutions like Bayt Dakira – a Judeo-Moroccan memory and spirituality center the king personally inaugurated – translates royal discourse about coexistence into physical spaces, festivals, museums and city branding.

When Mohammed VI walks through a restored synagogue or Jewish museum with his Jewish adviser at his side, the message is double: Jews are part of the Moroccan “we,” and their story is a resource for Morocco’s future – diplomatically, economically (heritage tourism, investment networks) and morally, as proof that a Muslim monarchy can anchor a genuinely shared civic identity.

After the 2020 resumption of ties with Israel, Moroccan Jews around the world described the king as “the guardian of our memory,” and many Israeli-Moroccan communities still recite blessings for him. He is referred to, as his father and grandfather before him, as “Sidna,” with a tone of reverence that survived decades and borders.

Anthropologically, the reason Jews respect Moroccan kings is a fusion of religious memory, cultural habitus and lived historical experience. Judaism is a tradition where kingship is sacred; Moroccan political culture is one where the sovereign is a paternal protector; and Moroccan Jewish history is filled with moments where the monarchy played a decisive role in their survival, dignity and identity.

Add to this the nature of diasporic nostalgia – where the land left behind becomes mythologized – and you understand why Moroccan Jews in Israel still raise toasts to “Sidna,” why they bless the Moroccan king at Mimouna, why they call Netanyahu “King Bibi” with a smile and why, generations later, the photograph of Mohammed V or Hassan II still hangs quietly in their homes.

- The author is a Moroccan journalist with a keen interest in Morocco-Israel relations and the long history of Jewish-Muslim coexistence in a country that was once home to some 250,000 Jews – the largest Jewish community in the region.