For Joseph Bau, survival itself was never a single act of heroism but a sequence of improbabilities that bordered on the miraculous. From evading execution to marrying Rebecca in the camps and finding her again after the war, he survived moments that logic could not explain.

Joseph Bau was born in Krakow in 1920. He was a young art student when the Nazis invaded Poland. His studies were cut short, but his creativity became a weapon.

Imprisoned first in the Krakow ghetto and later in the Plaszow labor camp under SS commander Amon Goeth, Bau became indispensable. Thanks to his mastery of Gothic lettering, calligraphy and graphic design, he was assigned to work for the Nazi administration and police, he designed signs, drew plans and produced visual materials

What the Nazis did not fully grasp was that Bau’s position and skill gave him power and access.

Bau’s greatest weapons were neither strength nor force, but art, language and humor. He used his skills as a graphic artist and calligrapher to forge documents, he helped prisoners obtain false identities, avoid transports and alter records, often under the eyes of his captors.

At the same time, he used humor to sustain those around him, telling jokes, writing poems and finding moments of laughter in places designed to crush the human spirit. This was not escapism but survival. “He understood that, as long as people could laugh, they were still alive,” says his daughter Clila Bau-Cohen.

A love story born in the camps

Joseph Bau’s greatest act of defiance may have been falling in love.

In Plaszow, he met Rebecca Tennenbaum. Their relationship itself was forbidden. They married secretly in the camp.

In a world designed to strip people of dignity and future, Joseph and Rebecca Bau made a radical choice. “They decided to fall in love, to get married, to be happy, and to save others," says Clila, describing a choice that ran counter to everything the Nazis sought to impose.

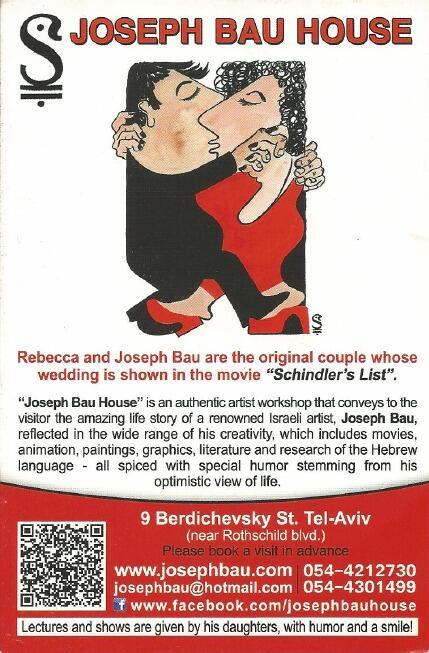

The wedding of Joseph and Rebecca Bau, held inside the camp, appeared briefly in Steven Spielberg’s feature film Schindler’s List.

Rebecca Bau’s hidden sacrifice

Rebecca Bau played an equally crucial role in surviving in the concentration camp. Fluent in German, she was forced to work as a manicurist for Nazi officers. While working, she listened. She passed information.

For this, she was punished brutally. She was once forced to stand naked for days in freezing conditions. The damage to her health lasted a lifetime.

At one point, Rebecca made a choice that would only come to light decades later. When a list was being compiled to transfer prisoners to Oskar Schindler’s factory in Brunnlitz, she persuaded a Jewish clerk to put Joseph’s name on the list instead of hers. She was sent to Auschwitz. Joseph survived and, over time, became Schindler's right-hand man.

She did not tell him the truth for 50 years. When she finally did, during an interview marking their 50th wedding anniversary, Joseph was stunned into silence. "I did it out of love," she said simply.

After the war, Joseph and Rebecca Bau’s reunion was nothing short of miraculous. Separated between camps, with no certainty that the other was still alive, they found one another through a chain of chance events that defied probability.

‘We grew up in a different kind of Holocaust survivors’ home’

At home, Joseph Bau was, above all, a devoted family man. His daughters recall a household in which respect and equality were not slogans but daily practice. He never asked his wife or daughters to serve him tea or coffee, and never expected them to clear dishes for him.

“Every morning he woke up happy,” his daughter Hadasa Bau recalled, “happy that he survived, that they didn’t break him, that he beat the Nazis.”

Joseph and Rebecca Bau did not raise their daughters in silence or shame; quite the opposite. The Holocaust was never a taboo subject, but neither was it allowed to eclipse life itself. “We grew up in a different kind of Holocaust survivors’ home,” says Clila. “Our parents knew how to communicate what they went through differently. They were not ashamed of the ghetto or the camps. They told their stories again and again, often with humor.”

“They spoke about survival as a miracle, but they added jokes, even dirty jokes, because that’s how people would listen. They were educators first and foremost. They wanted people to hear the story, to relate to it, not to turn away," says Hadasa.

Joseph Bau carried this approach into schools and public lectures, sometimes arriving in a striped uniform, using visual storytelling, humor and language to draw in audiences who might otherwise resist hearing such painful history.

Even so, they emphasized, he rarely spoke about what he did for others during the war. Acts of rescue, deception and protection were never presented as heroism. He never spoke about the people he saved or how many. He did not seek recognition.

“Only after our parents' death did we begin to understand the full scope of what they had done,” Hadasa says. “During their lives, they never spoke about saving others. We discovered it later, from survivors and from documents.”

He discouraged others from praising him. “He would change the subject,” Clila said. "We don’t talk about that," he would say.

Baus' contribution to Israeli culture and defense

Reinventing Hebrew through art

After making aliyah to Israel, Joseph Bau did something no one else had done before. He turned the Hebrew language into visual art.

Hebrew was not his mother tongue. Perhaps because of that, he noticed things native speakers overlooked. He explored reversals, wordplay and hidden structures.

For example, he illustrated how "לחם" - Lechem -(bread) and "לחם" - Lacham - (he fought) share the same letters and "מלחמה" - Milchama - (war) shares the same etymological root. Ironically, Holocaust prisoners were fighting to get access to bread.

He designed Hebrew fonts long before typography became fashionable. He also founded Israel’s first animation studio, creating early Hebrew-language animations and film titles. He also wrote 10 books, most of them published independently, choosing to self-publish all but his first to retain control over his language, illustrations and message. All of this happened in the same small building that now houses his museum.

Bau's vision - youth journeys to Poland

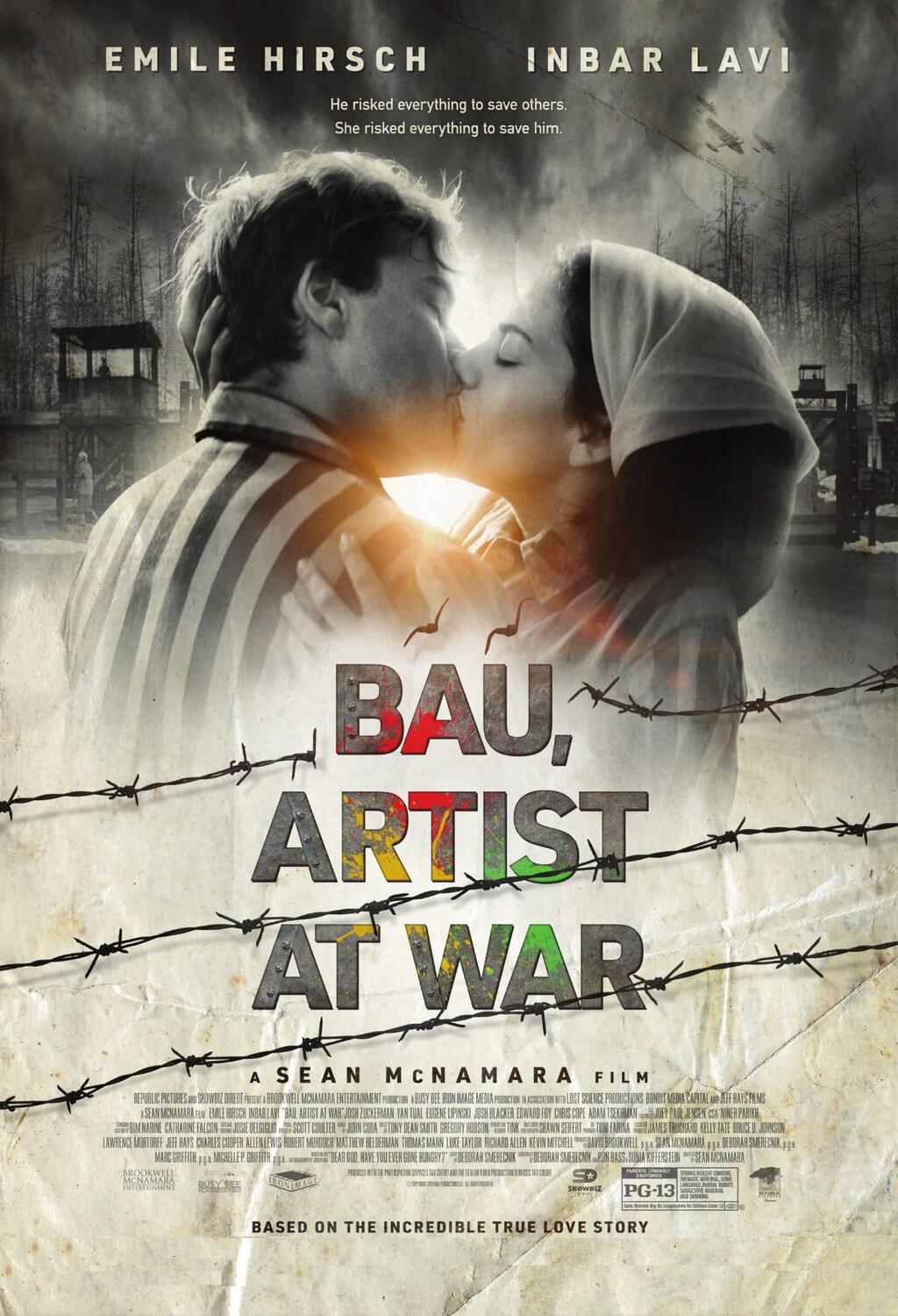

Bau: Artist at War is based on Joseph Bau’s memoir, originally published in English as Dear God, Have You Ever Gone Hungry?, a work that serves as a Holocaust testimony.

Bau did not write the book solely as remembrance. According to his daughters, he conceived it as a guide for readers who would one day walk through the camps themselves.

“He wrote it like a quiet companion,” one said. “As if he were walking beside you.”

The book leads the reader step by step through camp life, not to shock, but to orient. It explains how people moved, worked, hid, listened and survived. Bau understood that future generations would need more than facts. They would need context, emotional grounding and ethical direction.

That approach later informed his belief that Holocaust memory must be experienced physically, not only intellectually, and helped shape his early advocacy for bringing youth to Poland.

The memoir was later republished under the film’s title, Bau: Artist at War, reconnecting the written testimony to the cinematic retelling of his life.

From memory to belonging: Bau's idea came before Taglit

Years after the war, Joseph Bau believed that remembrance alone was not enough. He argued that Jewish continuity required a physical connection to the land of Israel, particularly for young Jews growing up abroad.

Long before the establishment of organized heritage programs, Bau advocated bringing Jewish youth to Israel not as tourists but as participants in a living national story. "This thinking later helped shape what became Taglit-Birthright Israel, embedding the idea that identity could be strengthened through firsthand experience," said Clila.

Quiet service beyond the spotlight

Beyond his well-known artistic and cultural contributions, Bau also assisted the state in sensitive security work, including discreet tasks for the Mossad, the intelligence community. His daughters stressed that he never spoke about this role publicly and refused to take credit for it privately.

Joseph Bau died in 2002, Rebecca in 1997. He was posthumously awarded recognition for "spreading the beauty of the Hebrew language in Israel and around the world."

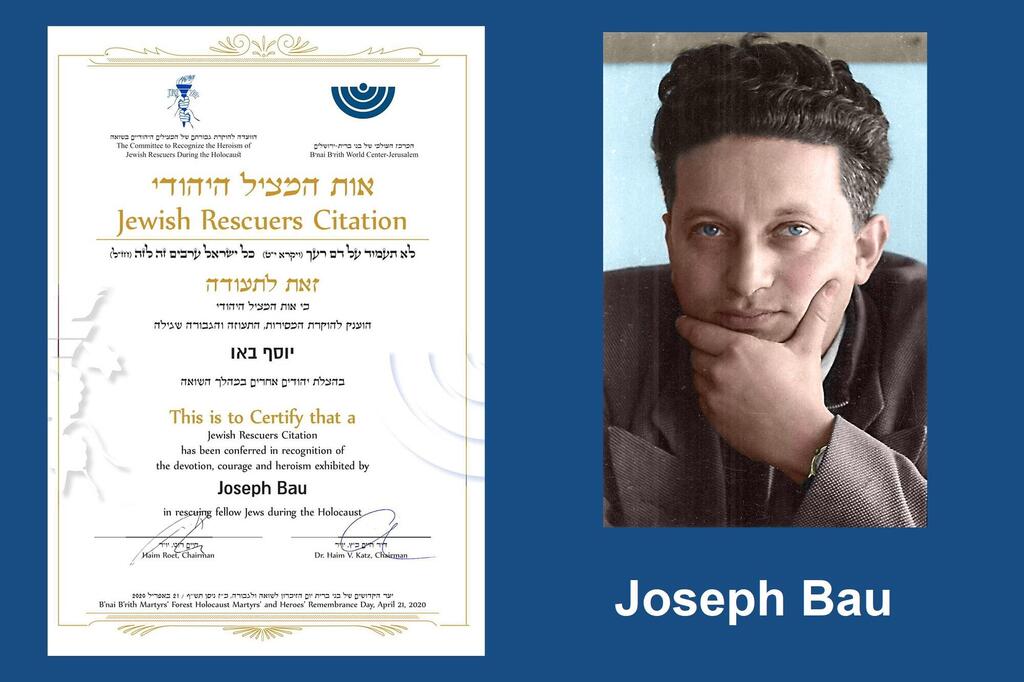

Further, in 2020, Joseph and Rebecca were awarded the “Jewish Rescuers Citation” from B’nai B’rith International.

Adapting a life of survival into a feature film

Bau: Artist at War, a Paramount film, directed by Sean McNamara and starring Inbar Lavi and Emile Hirsch, took 16 years to complete. It is based on Joseph Bau’s memoir Dear God, Have You Ever Gone Hungry? and its later expanded edition published under the film’s title.

Deborah Smerecnik, screenplay writer, recalled: "I came to Israel for the first time when I was 50, I had dreamed of getting to Israel. At the end of the trip I met Clila and Hadasa in Jerusalem when they came to tell their parents' story, and it just enthralled me. I said, 'It has to be made into a movie.'

"I had no experience, but I was determined to see their dream be done. It took me 16 years and lots of people I hired to write it, and eventually, because I was so dissatisfied with all the scripts I got, I decided to write it myself."

Smerecnik met director Sean McNamara, who was all excited about making this film, and through him they got Emil Hirsch, "who did an excellent job of playing Joseph Bau," Smerecnik said.

The film, its creators and the Bau family see the project not only as cinematic storytelling, but as an act of preservation.

Since its release, the film has screened in cinemas across the U.S., Canada and Australia, often followed by standing ovations and extended audience discussions. In several venues, cinema owners extended the run due to public demand.

In Israel, the film has been screened 3 times, accompanied by panels featuring Bau’s daughters and members of the creative team.

It will be further screened at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque on the following dates: January 27 (sold out), February 6 at 11 a.m., February 11 at 6 p.m. and February 28 at 1 p.m. Additional screenings are expected to follow across Israel, including outside Tel Aviv.

Internationally, the film is now available on demand streaming via Fandango at Home, Prime Video, Apple TV, YouTube and ROW8.

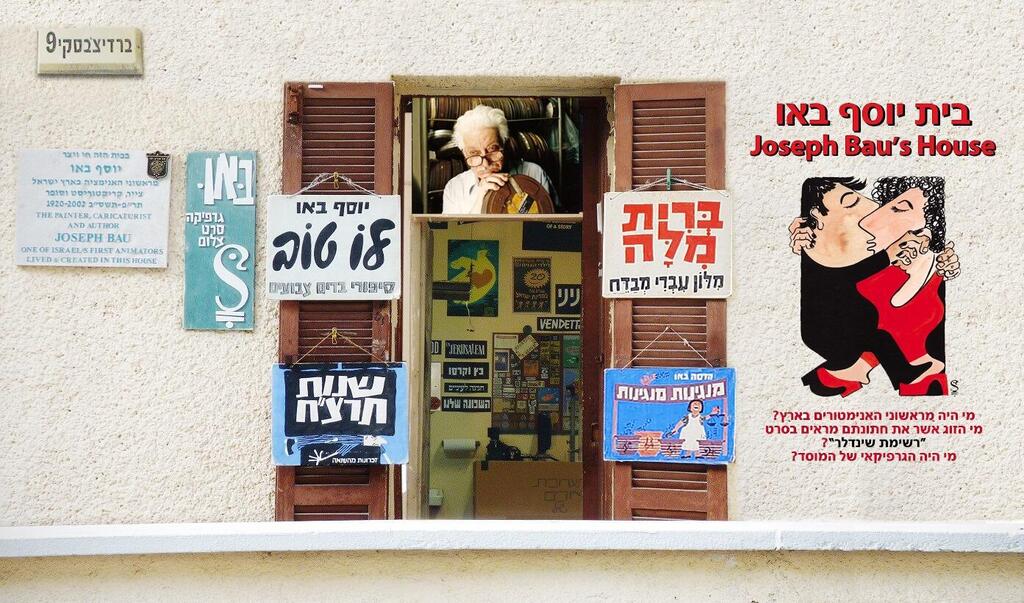

Saving Joseph Bau’s legacy - a museum unlike any other

The film has renewed attention to the Joseph Bau House Museum in Tel Aviv, located in the artist’s original studio. The museum preserves Bau’s cameras, artwork, typography, animation tools, his desk from before the war, his fonts, drawings, poetry, books, personal objects and documentation of his work during the Holocaust and in Israel’s early years. It is a journey from the Holocaust to Israeli cultural revival.

Students, soldiers, tourists, artists and Holocaust educators come from around the world. Evangelical Christian groups visit regularly. Many leave in tears.

"He gave up personal fame for Israel," Clila says. "The least we can do is make sure his legacy does not disappear," Hadasa adds.

As one visitor recently wrote in the guest book: "This museum changes how you understand survival."

Despite its cultural and historical significance, the museum currently faces an uncertain future due to redevelopment pressures and a lack of institutional funding. Bau’s daughters, who operate the museum, say its closure would mean the loss of a rare, authentic space that connects Holocaust survival, Hebrew culture, Israeli art and national memory under one roof.

The museum has received a Tripadvisor Travelers’ Choice Award, reflecting consistent high ratings and strong visitor engagement from audiences around the world.

A crowdfunding campaign has been launched to help secure the museum’s future. Visit here for more information and donations.