Two rare Orit manuscripts—sacred texts central to the liturgical and theological life of the Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jewish) community—have been identified as dating from the 15th century, making them the oldest extant examples of the Orit discovered to date. The find was made in the context of a traveling workshop operated by the Department of Biblical Studies at Tel Aviv University.

Prof. Dalit Rom-Shiloni, the founder and director of the program, explained that the term Orit—meaning "Torah"—derives from the classical Ethiopian language Ge'ez, itself drawing etymologically from the Aramaic "Orayta." Ge'ez, a liturgical language no longer spoken conversationally, serves as the sacred tongue of both Ethiopian Christianity and the Beta Israel.

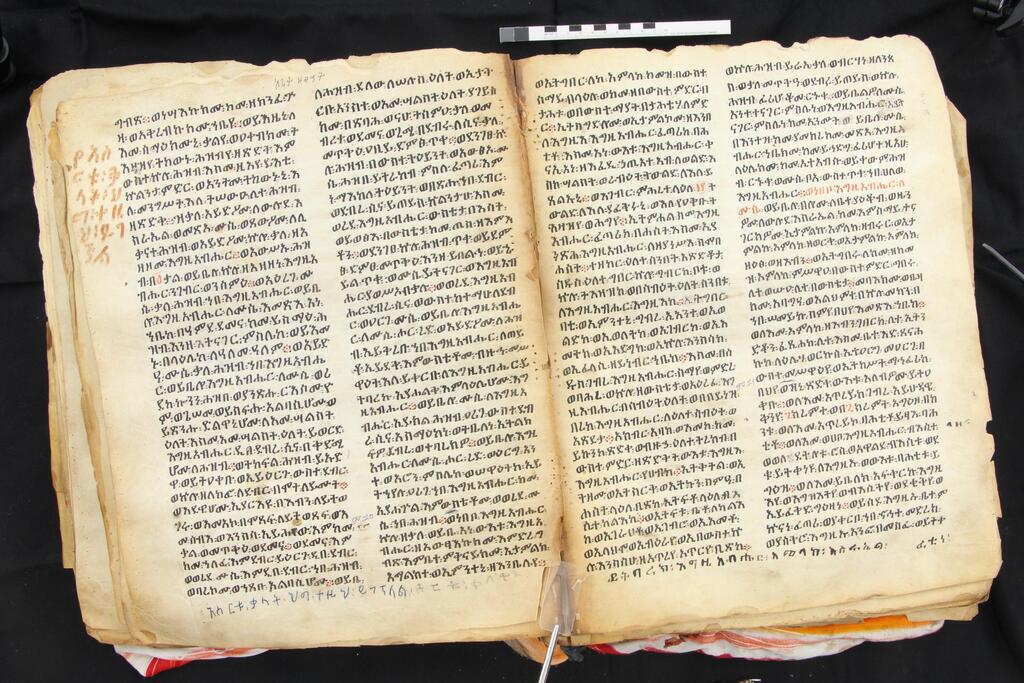

“The Orit texts,” Rom-Shiloni noted, “comprise the Torah and, subsequently, the books of Joshua, Judges and Ruth. These eight books form the earliest and most sacred portion of the Ethiopian Biblical canon.” These manuscripts, written in Ge'ez script, are part of a manuscript tradition spanning centuries, but extant specimens from as early as the 15th century remain exceedingly rare.

“While the Ethiopian manuscript tradition is known from the 14th to the 20th century,” she continued, “surviving sacred texts from the 14th century are extremely few, and even those from the 15th century are scarce. What we have uncovered is that among the kesim—the religious leaders of Beta Israel—residing in various parts of Israel, there exist manuscripts preserved from the early and late 15th century. This had not been known to the scholarly world.”

A mission to preserve and study

The initiative’s name, roughly translating as "Catchers of Orit", is drawn in parallel to a term employed by the prophet Jeremiah, who refers to scribes or priests as "those who grasp the Torah." In this spirit, Rom-Shiloni coined “those who grasp the Orit” with the vision of forming a scholarly cohort composed of students from the Beta Israel community, alongside others, who would be trained in the textual, linguistic and exegetical traditions of these sacred writings.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“This requires expertise,” she explained. “The program is housed within the Biblical Studies department and involves instruction in translation traditions, philology and the hermeneutical practices of Ethiopian Jewry.”

Manuscript fieldwork among the kesim

When asked about the practical work undertaken by program participants, Rom-Shiloni described a unique blend of textual scholarship and field engagement. “We visit communities in search of missing or unrecognized manuscripts. As a biblical scholar, I was trained to work with written texts. Here, we are afforded a rare privilege: direct dialogue with kesim.

"There are fewer than twenty elder kesim in Israel today—men who were ordained in Ethiopia prior to their community’s migration—and they are custodians not only of manuscripts brought at great personal risk but also of oral traditions, liturgical knowledge and interpretive customs.”

She emphasized the interpretive role of the kesim as mediators between the ancient language of the text and the vernacular languages of the community—typically Amharic or Tigrinya.

“The kesim translate the Torah during liturgical readings—not from a neutral standpoint, but according to inherited tradition. They insist this is the tradition as they received it.”

Living texts and the ethics of preservation

When asked whether the manuscripts are accessible to scholars or the general public, Rom-Shiloni was clear: “These are living texts. They are not museum artifacts but sacred books still in active ritual use. They are carefully guarded by the kesim, and until now, no public access has ever existed.”

In collaboration with the National Library of Israel and the Ethiopian Jewish Heritage Center, the program has begun building a digital repository. “The manuscripts remain in the hands of their guardians,” she stressed. “We don’t remove them from the community. Instead, we bring cameras to the manuscripts—never the other way around.”

Currently, the digital archive holds seventeen sacred manuscripts, including the two 15th-century Orits. Rom-Shiloni believes this is only the beginning. “We are eager to expand the archive. We know many singular manuscripts are still held by families across Israel. We earnestly call upon the kesim and their descendants to work with us in preserving this invaluable heritage.”

Are there even older orits yet to be found?

“I hope so,” she replied. “We’ll see. The truth is, we don’t know. What I can say is that in this research, each week brings new discoveries. It’s a realm that has only now begun to open itself to scholarly inquiry.”