About 400,000 Jews immigrated to Israel from Romania during the Communist era, the second-largest wave of aliyah in the country’s history. For decades, the story was told as another chapter in the Zionist struggle and the yearning for freedom. Newly uncovered documents and testimonies, however, point to a far more complex picture.

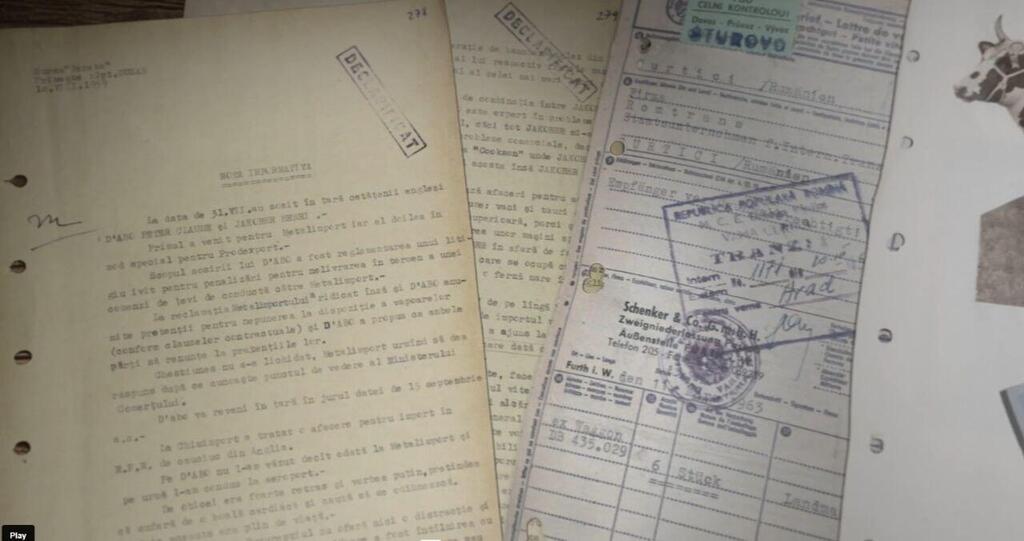

Behind the steady flow of Romanian Jews to Israel operated a sophisticated political and economic mechanism that included secret understandings, financial incentives and prolonged intelligence activity.

The findings were presented for the first time at the Yitzhak Artzi Forum of the A.M.I.R. organization, in cooperation with Nativ. Military historian Col. (res.) Dr. Benny Michelson presented archival documents, testimonies and personal accounts shedding light on the diplomatic background that enabled Jewish emigration over decades.

A quiet mechanism behind closed doors

After World War II, Eastern European countries sealed their borders. Romania was almost the only state that allowed continuous Jewish emigration — but not without compensation. According to the documents, aliyah was accompanied by political and economic arrangements, sometimes indirect and sometimes entirely covert.

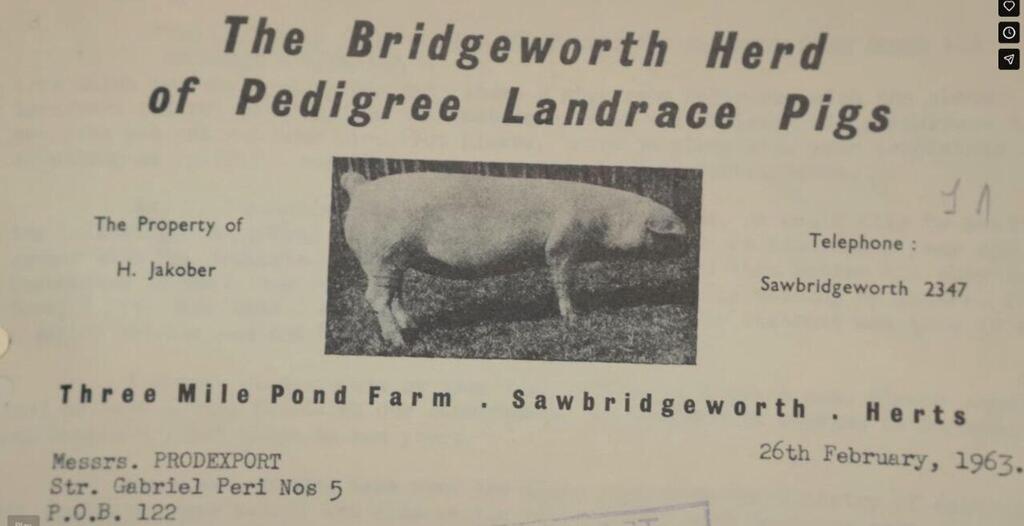

Agricultural assistance, infrastructure equipment, drilling facilities, state credit and the supply of technology were used as bargaining tools. Within this system, an unofficial term took hold: “chicken coops for Jews.”

Between 1961 and 1965 alone, about 80,000 Jews immigrated to Israel under such arrangements. Estimates suggest Romania earned tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars in contemporary terms — not through a single dramatic deal, but through a steady stream of agreements and understandings.

Alongside Nativ, which operated as a diplomatic and covert arm, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee played a central role in financing operations and providing loans that sustained the arrangements.

Micha Harish, chairman of A.M.I.R., said the newly revealed materials make it possible “to understand in depth the decisions and agreements that enabled aliyah from Romania over five decades — a process that was far from self-evident in the Communist bloc.”

The house filled with medicine

Beyond the economic data, personal stories illustrate the human cost.

Actress Sandra Sade recalled that as a child in Romania, she sensed something unusual in her family home. People came and went; whispers and fear filled the air. Only later did she understand that her family had been involved in clandestine efforts to transfer essential medicines to Jews at a time when antibiotics and morphine were scarce and sometimes prohibited.

“The bathtub at home was full of medicine,” she said. “Couriers would come, take it and ask no questions.”

The price was heavy. Her father was repeatedly arrested and sent to forced labor along the Danube, dismantling sunken ships, a particularly dangerous task. In 1964, her mother immigrated to Israel with the children and elderly grandparents, while her father remained behind in prison. The family was reunited only later.

Another story is that of Dudi Ben-Yishai, born in 1928 in Iași County. His family immigrated to Israel in 1950, leaving him alone in Romania. For 12 years, he worked as an engineer in Bucharest while secretly engaging in Zionist underground activity at a time when any connection with Israel was considered a serious offense.

His daughter, Dr. Galit Cohen, said he operated through coded messages, brief meetings in public places and briefings conducted in the shower with running water to avoid surveillance. After the regime fell, he approached the Securitate archives and discovered the scope of monitoring: 12 thick files documenting every step he took.

In March 1961, he was arrested, interrogated harshly and sentenced to severe punishment. In April 1962, on the eve of Passover, he was released as part of a deal and reached Israel, where he built a new life without seeking recognition or speaking publicly about his activities.

Between East and West

On the diplomatic level, Romania enjoyed a unique status. It was the only Communist bloc country that did not sever relations with Israel after the 1967 Six-Day War, while at the same time maintaining ties with the Palestine Liberation Organization. This dual position granted it significant political and economic leverage.

Even in the 1990s, when Bucharest became a central transit point for Soviet Jewish immigration to Israel, similar financial mechanisms reportedly continued to operate.

The newly revealed materials portray Romanian aliyah not as a one-dimensional heroic tale, but as a prolonged and complex process involving political compromises, economic arrangements, personal risks and covert networks.

Behind every statistic stood individuals — and often a heavy price. The immigration from Romania was not only a national achievement, but also the result of sustained negotiations in which policy, economics and personal destinies were tightly intertwined.