Athaliah, queen of Judah, is described in the Bible as the first woman to rule the kingdom — and one of its most infamous. Her story begins with a massacre: a queen who slaughtered her own descendants and those of her husband to eliminate rivals to the throne. She ultimately lost power to a child — her own grandson, Joash. But how did she rise to power, what led to her downfall, and was she truly as wicked as tradition suggests?

A queen outside the House of David

Athaliah was born into the royal family of Israel, a daughter of King Ahab, one of the most powerful monarchs in the northern kingdom. She married Jehoram, king of Judah, and the couple had a son, Ahaziah. When both her husband and son died, the throne of Judah was left vacant.

In the royal palace remained Athaliah, the widow, mother of two dead kings, and an outsider to the Davidic line. Determined to secure power, she took brutal action:

“When Athaliah, the mother of Ahaziah, saw that her son was dead, she arose and destroyed all the royal heirs.” (2 Kings 11:1)

Her motive was straightforward — to silence any potential claimants to the throne. Centuries later, when Niccolò Machiavelli wrote The Prince and praised Cesare Borgia for eliminating his rivals, he may well have found inspiration in Athaliah’s calculated ruthlessness.

Athaliah’s reign was exceptional not only because she was Judah’s only non-Davidic ruler but also because she was its only female monarch. According to Rabbi Nehemia Steinberger, of Jerusalem’s Ohel Yitzhak synagogue and host of a Bible studies podcast, times of chaos often create space for women to step into leadership. “In the era of the Judges, when ‘there was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes,’ we suddenly meet Deborah the prophetess, Delilah who brings down Samson, Jael who kills Sisera, the woman of Thebez who crushes Abimelech’s skull, and Naomi and Ruth who establish Israel’s royal lineage,” he explains.

Steinberger also draws parallels between Athaliah and Jezebel — Ahab’s wife, a priestess of Baal and an influential political figure whose power shaped her husband’s reign throughout the Book of Kings.

The prince hidden in the Temple

During the massacre, one infant escaped Athaliah’s reach: Joash, her grandson and the last surviving heir of the House of David. His aunt Jehosheba, the daughter of King Jehoram and wife of the priest Jehoiada, realized the danger and hid the child and his nurse inside the Temple.

For six years, Joash lived in secrecy within the Temple walls, while Athaliah ruled Judah with an iron hand. In the seventh year, Jehoiada decided the time had come to restore the Davidic line. He gathered the captains of the guard — the Temple priests — divided them into three groups, and armed them with King David’s ancient spears and shields, said by some to bear the first “Star of David.”

As the priests lined the Temple from end to end, Jehoiada brought out the young prince, placed the crown on his head, and handed him the Torah scroll — the symbol of royal authority.

“He brought out the king’s son, put the crown on him, and gave him the testimony; they made him king and anointed him, and they clapped their hands and said, ‘Long live the king!’” (2 Kings 11:12)

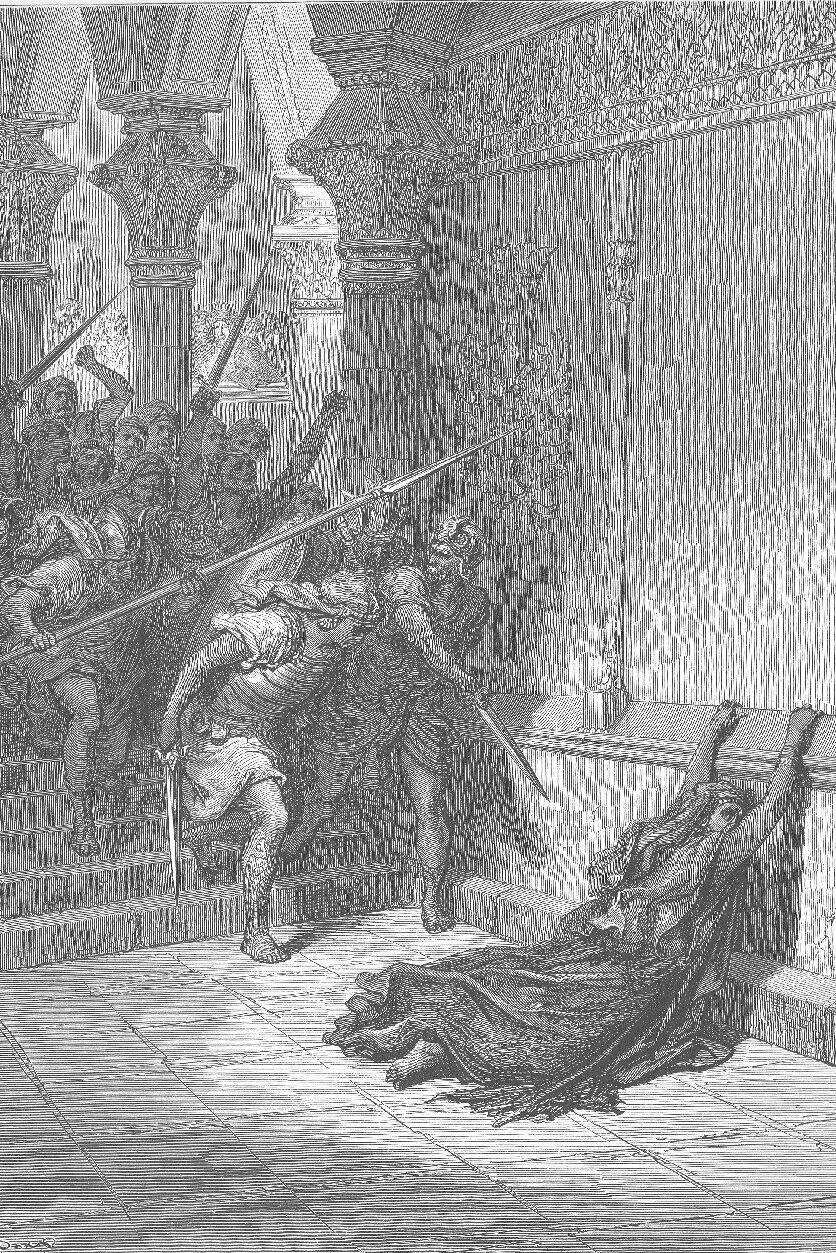

The celebration echoed through Jerusalem, reaching Athaliah’s palace. Hearing the commotion, the queen rushed to the Temple and saw the boy seated on the royal platform, surrounded by cheering crowds. Realizing the coup, she tore her clothes and shouted, “Treason! Treason!”

Jehoiada ordered that she not be killed in the Temple, so the guards cleared a path for her to exit through the “Horse Gate” to the royal palace, where she was executed.

The 'wicked queen' in Jewish memory

The Book of Chronicles later refers to her as “Athaliah the wicked woman,” noting that “her sons broke into the house of God” (2 Chronicles 24:7). Yet, surprisingly, the main account of her reign in the Book of Kings contains no such explicit condemnation. Unlike other rulers, it does not say she “did evil in the eyes of the Lord.”

Some scholars argue that the story of the massacre may have been exaggerated or even fabricated by those who sought to justify her overthrow. The Bible, which is less a historical record than a moral and theological narrative, portrays Athaliah not merely as a sinner but as a threat to divine order — the first to challenge the Davidic dynasty, a line so central to Jewish faith that Maimonides later enshrined belief in its continuation as one of Judaism’s core principles.

Rabbi Steinberger adds that ancient fears of powerful women likely shaped how Athaliah’s story was remembered. “The verse says, ‘You shall not allow a sorceress to live’ — not a sorcerer,” he notes. “Women were thought to kill through poison rather than the sword, and qualities like cunning, mystery, and dark magic were projected onto them.”

Legacy of blood and fear

Athaliah’s end, as described in the Bible, was surprisingly restrained — a swift execution rather than a civil war. Her grandson Joash was crowned king at just seven years old and ruled for 39 years. Early in his reign, he abolished idol worship and followed the guidance of his uncle, the priest Jehoiada, initiating reforms to restore the Temple.

But after Jehoiada’s death, Joash’s reign took a dark turn. Influenced by his officials, he allowed idol worship to return and even ordered the execution of his cousin, Zechariah son of Jehoiada, who rebuked him for his sins.

A year later, King Hazael of Aram attacked Judah, forcing Joash to buy temporary peace with heavy tribute. Hazael eventually advanced on Jerusalem, defeated Joash’s forces, and left him wounded and bedridden. Two of his own servants, Zabad and Jehozabad, assassinated him in his bed — a grim end for a king once hailed as the savior of David’s line.

The woman who challenged the divine order

Centuries passed before another woman ruled Judah — Queen Salome Alexandra of the Hasmonean dynasty. Athaliah, meanwhile, remained a cautionary figure in Jewish memory: the queen who dared to claim power, to threaten the sacred lineage of David, and to defy the order of her world.

Whether villain or visionary, Athaliah’s story continues to echo as a reflection of how history — and tradition — judge women who seize authority in a man’s world.