While her ultra-Orthodox brothers take part in protests chanting, “We’d rather die than enlist,” 18-year-old Tzipora dreams of serving in the IDF’s combat intelligence collection unit and is enrolled at the Geva pre-military academy program, which brings together secular young people with those who, like her, have left the ultra-Orthodox community.

Tzipora is a descendant of Rabbi Abraham Isaac HaCohen Kook (the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel, who is considered one of the fathers of Religious Zionism). Over the years, her family became increasingly Haredi.

She is the eldest of eight children. Her family moved between several ultra-Orthodox communities, including Telz Stone, Modiin Illit, and Beit Shemesh. Her father works in music and event production, and her mother is a secretary at an elementary school.

“By seventh grade, I understood the Haredi way of life wasn’t right for me,” she says straightforwardly. “I felt different, but kept it all inside. Maybe I was a bit rebellious, but on the outside I looked like a regular Haredi girl."

Did you tell your parents?

“No. When I was in fifth grade, my uncle, who had left ultra-Orthodox and religious life, came to visit. He had tattoos, and I saw how my aunts ran into a room crying in shock. That scared me, so I decided not to reveal anything about myself."

Were you at least in touch with him?

“No, because he distanced himself from the family. That showed me how my family views people who leave religion. The only ones who really knew about me were a few close friends. We were a group of five girls who didn’t quite fit the system. We supported each other.

"Not all of them were secular, so when we met on Shabbat, for example, I wouldn’t take out my phone, but there was sharing and acceptance. To earn some money, I babysat and cared for hospital patients on Shabbat. That also helped me avoid being home on Shabbat."

When did you finally tell your parents?

“I switched between a lot of schools, and in 12th grade I studied through HILA, a program for youth who have dropped out of formal education frameworks, operated by the Education Ministry. I was afraid to have the conversation with my parents, so I spoke to my teacher and principal.

"They invited my parents for a meeting to tell them I was thinking of leaving religion and planned to enlist in the army. After they finished speaking with my parents, I walked into the room wearing pants. I told them everything the teacher and principal said was true, and they were in shock."

How did your parents and siblings react?

“My parents are trying to accept me because family is important to them, but they’re afraid I’ll influence my younger siblings. So I try not to be around, and there’s a certain distance."

Surviving without family support

Unlike her Haredi friends who received automatic exemptions from military service, Tzipora (her full name is withheld) deliberately stayed home whenever her classmates went to file for exemption through the school. Her biggest dilemma was how to prepare for combat service without any family backing and with almost no familiarity with secular life.

She attended an “exposure day,” where she learned about her enlistment options and various pre-army programs. She was especially drawn to the Geva pre-military academy, run by BINA and the Ma’ase Center, which brings together former Haredim and broader Israeli society.

A few months ago, the Geva pre-military academy completed its first course, which included former members of the Haredi community. The program is now led by Yaron Ohayon, a graduate of the IDF’s military boarding school in Haifa who later served as a paratrooper and commanded a company at the IDF’s officers’ training base.

At their first meeting, Tzipora told Ohayon she was eager to join the program and saw it as the perfect stepping stone to prepare for military service, but she couldn’t afford the tuition, which includes full room and board.

“Yaron told me, ‘If money is the issue, I won’t let that stop you from studying,’” Tzipora recalls. “Not only did I receive a scholarship, they even arranged for a small budget so that on weekends, when other students went home, I and the other formerly religious participants could buy food and be together."

Terry Newman, chairman of BINA public board, noted: “Geva allows young people who left the Haredi community to reconnect with Judaism but in a different way than they were taught.

"We realize that Israelis are seeking Jewish identity, and through this program and BINA’s other initiatives, we’re giving them the tools to take ownership of that identity and help shape an Israeli Judaism that’s more inclusive and open than how the rabbinic establishment tends to portray it."

4 View gallery

Tzipora (seated on the left) with her fellow pre-army academy students

(Photo: Bina - Ma'ase center)

Yossi Malka, CEO of the Ofek Council of Pre-Military Academies, added: “Geva represents the essence of the Ofek initiative, bringing together participants from Haredi backgrounds with those from traditional communities for a meaningful shared journey and serious preparation for combat service in the IDF.

This partnership between BINA and Ma’ase is crucial and should continue to produce capable soldiers and citizens who help build Israeli society."

'I was afraid lightning would strike me, but even more afraid of running into family'

“This year we’re 16 ex-Haredim in the program,” says Tzipora. “On our first Shabbat together, we went to the beach."

How did that feel?

“I knew the punishment for violating Shabbat is stoning, and it felt strange that there was public transportation on Shabbat. I was asking, ‘Wait, how can there be a bus? And how is it that you don’t even have to pay for it?’” she says, laughing. “It was as exciting as learning to walk, discovering a whole world I hadn’t known existed, and realizing it’s okay to live in it."

Were you afraid of 'being struck by lightning'?

“I was, but I was even more afraid of running into a relative. But it was Tel Aviv, so I didn’t see anyone I knew."

Tzipora says the Geva program includes classes on Zionism and Israeli-Jewish culture, leadership development, community engagement and volunteering, as well as physical and mental preparation for army service.

“I wasn’t prepared for my first military order, so my Dapar test score reflected that,” she says. “But now I’m getting ready seriously. Unlike many others who just want to finish their military service and move on, for me the IDF is a goal, not just a phase. If I can get into a meaningful role, I’m fine with a longer service."

And what do you think about the current crisis over Haredi enlistment?

“While there’s a war going on, my huge family, including many cousins, not only isn’t contributing, they’re out protesting against the draft. I tried talking to them, but it’s just part of who they are. They only listen to rabbis and fundamentally reject Israeli societal values. They really would rather die than enlist."

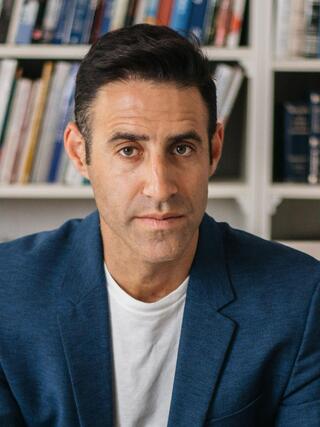

Terry Newman. "Israeli Judaism"Photo: Meidan Hemo, Lax studio

Terry Newman. "Israeli Judaism"Photo: Meidan Hemo, Lax studioSo what’s the solution, in your opinion?

“There needs to be dialogue with the rabbis who actually make the decisions. In the end, it's just three or four of them who decide for the entire Haredi public.

"Someone needs to explain to them how serious the situation is, how military service is a duty and a privilege, and how Haredim can serve in the IDF without giving up their identity. Maybe that would help."