Can a song by Hadag Nahash resonate with a Jewish teenager in New York? What can American Jews learn about Israeli resilience after October 7? And what does singer and actor Idan Amedi represent to Jewish college students in Los Angeles?

Questions like these drive Jake Gillis, a recent immigrant who fell in love with Israeli culture and is trying to teach Jews in the U.S. the secret behind Israel’s unique appeal.

Gillis was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, home to a Jewish community of about 50,000. He says he always felt drawn to Israel and visited frequently, including a semester at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem as part of a student exchange program. In 2019, at age 21, he decided to make aliyah.

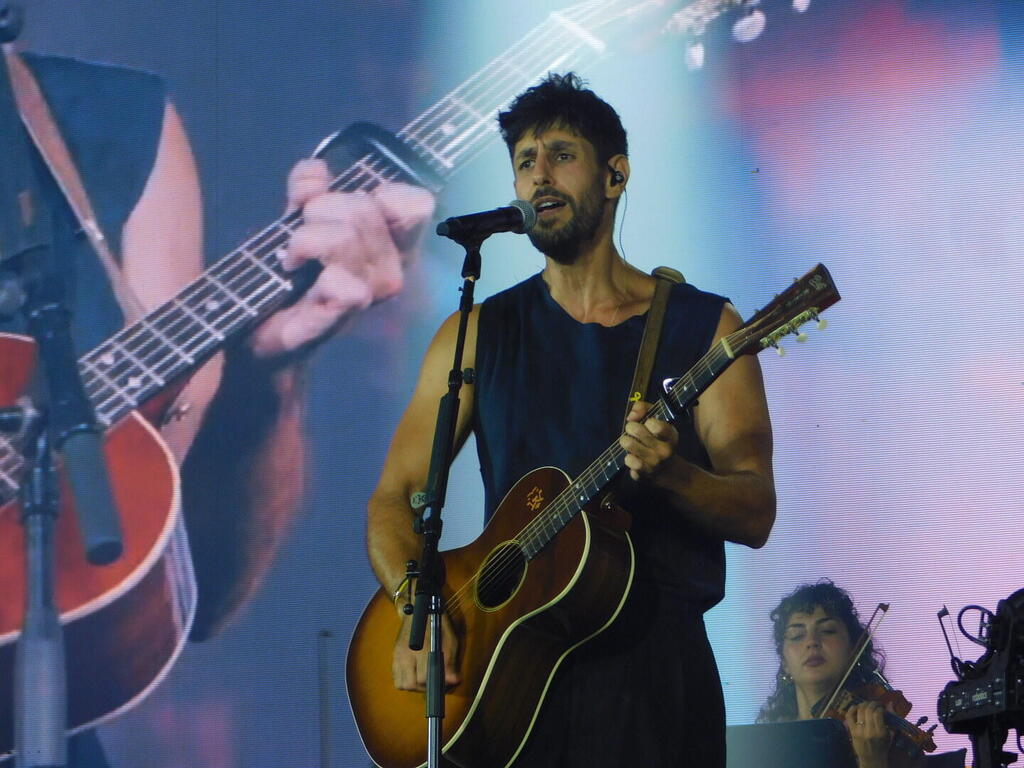

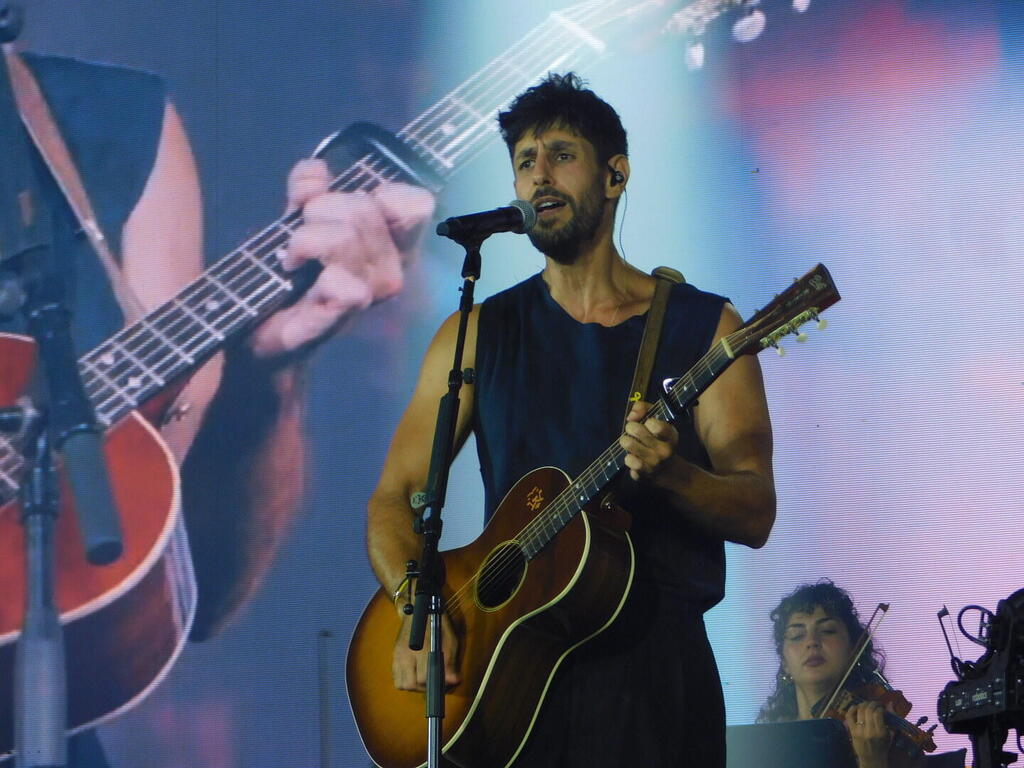

5 View gallery

Idan Amedi. A symbol of Israeli resilience, including in the Diaspora

(Photo: Shahar Amano)

“After I finished my degree in the U.S., I realized it was basically now or never, and I decided to move to Israel on my own, without my family,” he said. “It wasn’t easy, but it was something I truly wanted. I felt so connected to Israel. I knew people here and wanted to be part of it.”

He describes ups and downs along the way. Over time, he said, things became easier. He met his wife, who is also an immigrant, and the couple now lives in the suburbs, as it feels calmer, more like a relaxed family life, he said.

Following the COVID pandemic, wars and turbulent days in Israel, Gillis concluded that his mission was to make Israeli culture, particularly music, accessible to American Jewish audiences.

Since October 7, his English-language podcast “Sababoosh” has featured in-depth interviews with Israeli artists, introducing them to American listeners while unpacking the nuances of their work and of Israeli popular culture.

“In addition to interviews, I write posts and articles about slang and language to present the Israeli mindset to Jews in the U.S.,” he explained.

What sparked your interest in Israeli culture? In many cases, new immigrants remain closely connected to the culture of their country of origin.

“When I went to a Jewish summer camp at around 15, I met a delegation of Israelis there. There was a counselor in my age group who taught us some Israeli slang. It was so clever, and the way the different words connected and created deeper meaning made me fall in love with it. That was my entry point into Israeli culture, through Hebrew and slang.

He began listening to Israeli music in high school and learned more about Israeli society through TV series and reading about artists.

(“Eretz” by Idan Raichel. Expresses a yearning for renewal)

Which Israeli artists have also managed to break through with American Jewish audiences?

“I think in recent years you can point to Ishay Ribo and Benaia Barabi, and there are quite a few people, like me, who really love Hadag Nahash.”

As an American Jew, can you understand the nuances in Hadag Nahash’s lyrics? These are complex messages.

“Yes, there’s so much meaning behind it. I don’t think I truly understood it in high school, but over the years you learn the political meanings. If you’re curious, like I am, you dig deeper and try to understand why they wrote things a certain way. As your Hebrew improves, you feel more connected to the text and to the work itself.”

But there is a language barrier and nuances that are sometimes very Israeli. Can American Jews really understand and connect to it?

“Sometimes it’s not easy, but if you break down the text, talk about the words and their meanings, and explain them even to non-Hebrew speakers, they gain cultural context. My goal isn’t to translate literally, because any translation software can do that, but to provide context and make it more accessible to an outside audience.”

5 View gallery

Jake Gillis. “Many Jews are more engaged with what’s happening in Israel and are looking for ways to connect”

Is this of interest to non-Israeli audiences at all?

“I think so, especially since October 7. Many Jews are more engaged with what’s happening in Israel and are looking for ways to connect. One way is cultural. They want to read a book by an Israeli author, watch an Israeli film or listen to Israeli music. It’s partly curiosity, but also a desire to feel closer. It doesn’t necessarily replace their American culture, but it becomes another layer.

On the other hand, some people aren’t interested, and that’s perfectly fine. I want to make it accessible for those who are curious and want to learn more about Israel in cultural contexts.”

Reaching a new audience through art and culture

Among the guests on his podcast have been writer Etgar Keret, musician Ivri Lider, TV producer Assaf Gil, filmmaker Joseph Cedar and radio host Achinoam Bar. He has also hosted figures who seek to explain the fabric of Israeli society, including Alex Rif; Prof. Haim Noy, who discussed the Israeli phenomenon of the post-army trip; and mentalist Guy Bavli, who explored why Israel has produced so many illusionists.

Do you find it easy to secure guests for a podcast that isn’t really aimed at their core audience?

“It’s much easier than I expected. People in Israel are relatively accessible, and I was quite surprised by how many are open and respond to regular WhatsApp messages, even if it’s not exactly their core audience. Some of them saw it as an opportunity to speak in English to Jews in the U.S., perhaps to connect with them and explain their work to a new audience.”

Gillis noted that since October 7, the trend of Israeli artists seeking to develop English-language careers and reach new audiences has intensified, citing the English stand-up performances of Yohay Sponder and Shahar Hasson as examples.

“Both sides need to understand that there are cultural differences, but also differences in definitions", says Gillis. "A secular or ultra-Orthodox Jew in Israel will not necessarily be the same in the U.S.

Israelis, and American Jews alike, need to understand that there are many shades of Judaism and of Jewish identity, and not everyone fits into the same definitions.”

“Music reflects hope and a desire for renewal”

Gillis’ current focus centers on Israeli music in the aftermath of October 7.

“In my view, the music has changed in certain ways, and it can be an interesting lens through which to look at what has happened since October 7, not only in terms of war and pain, but in the culture itself and in resilience,” he said.

“My research shows that the vast majority of Israeli music since October 7 has been infused with hope. There are certainly songs that express mourning and pain, and some that seek revenge or provide an outlet for anger. But I also found a great deal of hope and a desire for renewal. The message in many songs is that we took a very hard blow, but it is worth fighting for tomorrow.”

(“Basof Ani Magen David.” A message that it is worth fighting for tomorrow)

In which songs, for example, is that most evident?

“‘Eretz’ by Idan Raichel, ‘Vayehi Or’ by Hatikva 6, ‘Basof Ani Magen David’ by Avihu Pinhasov’s Rhythm Club and of course ‘New Day Will Rise,’ Israel’s recent Eurovision entry performed by Yuval Raphael.

Beyond those examples, I built a lecture that tries to illustrate for Jewish audiences in the Diaspora what music means to Israelis and how collective singing, for example, is a very important social and cultural element here. Not just communal sing-alongs in the old sense, but singing in Memorial Day gatherings in city squares or in special concerts where audiences sing in unison. There is enormous power in that.

I also talk about the power of radio and particularly stations like Galgalatz (radio station operated by the IDF), which is often a barometer of the national mood.”

Music, he added, can also be healing. He cites Idan Amedi as an example of resilience, especially after the singer was seriously wounded while serving in the reserves during the war. Amedi later released the song “Superman,” which reflects on vulnerability and strength.

“There is clearly post-trauma here,” Gillis said. “But one of the first Hebrew expressions I learned was, ‘We survived Pharaoh, we’ll survive this too.’ That probably captures our current situation.”

Do American Jews still view Israelis as resilient, despite everything that has happened?

“Yes. The image of the tough, strong sabra is still very dominant. Many American Jews have come to Israel over the past two years to volunteer and help, and I think there is admiration and a desire to connect to that resilient identity. By coming to contribute and assist, they also connect to it and strengthen themselves.”