Many Jewish families who immigrated to Israel from the former Soviet Union celebrated Novy God on Wednesday night, the holiday marked on New Year’s Eve. Alex Rif, CEO of the Lobby of the Million advocacy group, is fighting for the holiday associated with immigrants from the former Soviet Union to gain recognition in Israel. She says the public discourse around it in Israel is rife with ignorance and prejudice.

“I have to say that until two or three years ago, I always thought we were on an upward trend,” Rif told ynet. “The ‘Israeli Novy God’ project, the big campaign we launched just to explain what it even is, took place exactly 10 years ago. We were young students. We felt we wanted to bring our culture out into the open, and it exploded. There were many shares and media interviews. Since then, we thought it was only growing, and that maybe we didn’t even need to do anything anymore. But in the past two years, I actually feel the opposite. Suddenly there is much more ignorance, and in more and more places people feel comfortable criticizing and saying, ‘You’re Christians, you’re not Jewish enough.’ That means our work is far from over. The danger may even be greater, and it is our duty to talk about Novy God.”

What do you think explains the sense that something has changed over the past two years? What drove it? People still ask you what “Novy God” is, assuming it’s the name of a holiday or something connected to Christianity, when in fact it is simply a literal translation meaning “New Year.”

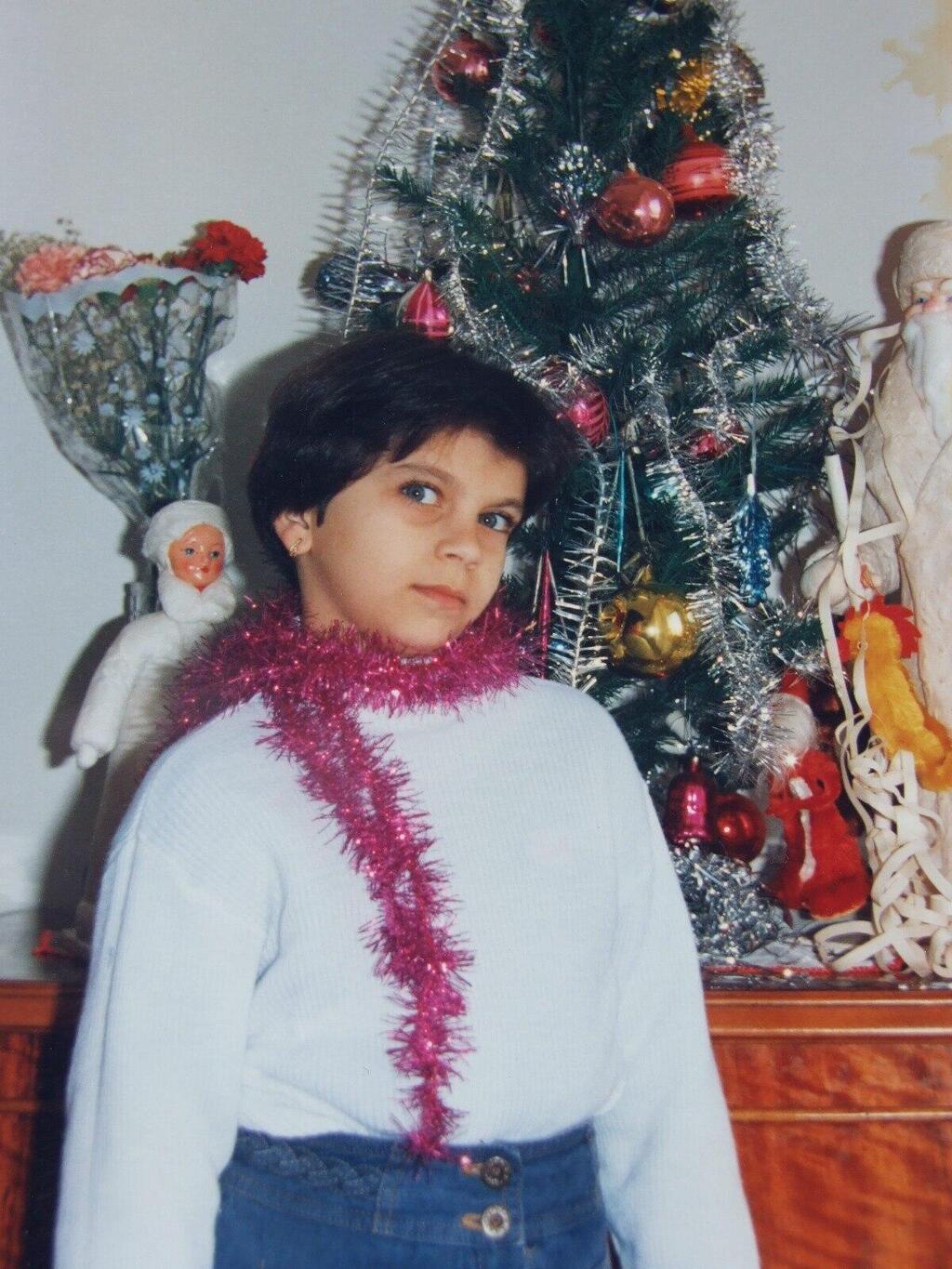

“There was an exchange on Facebook where someone wrote to me: ‘Now that I understand what Novy God is, I don’t understand why you insisted on continuing to call it Novy God and not simply New Year,’” Rif said. “That decision we made, a group of what we call the ‘one-and-a-half generation,’ 10 years ago, came from wanting to bring something from our home — something of the excitement we feel around this holiday — and not just call it ‘New Year’ like the rest of Europe or other countries. And still people don’t know. They still say, ‘Wait, but if there’s a Christmas tree and Santa Claus, it must be a Christian holiday. You’re Christians. This isn’t Jewish.’”

“That’s where I start telling the story and explaining that the Judaism of the Soviet Union underwent a complete religious erasure,” she said. “For 70 years, Judaism was banned. There was one holiday that wasn’t communist — meaning there was no requirement for citizens to go to parades or take part in ideological activities — and that was Novy God. It was a family, home-based holiday where you could sit together with friends and let go a bit. That’s why this holiday was so important to Russian speakers, and why it remained in their hearts even after they immigrated to Israel.”

You say there was a religious erasure, but at the same time there was no Christianity either. There was only communism. Novy God doesn’t really have clear Christian symbols, but it did adopt elements that resemble Christmas, like the tree and Santa Claus. In Russian, the parallel figure is called Ded Moroz, or “Grandpa Frost.”

“The Soviet regime borrowed symbols from many places,” Rif said. “The yolka, the name for the New Year’s tree, is an evergreen that is very familiar to children. They would decorate it in the winter to make them happy. Grandfather Frost is simply a character from old Slavic folk tales. It’s true that Christianity also appropriated some of these symbols, but what’s clear is that Jews from the Soviet Union celebrate a civic holiday that sums up the civil year and blesses the new one. That’s wonderful. Great — let’s find another reason to celebrate. And for me, above all, this is an opportunity to bring people closer and say: Friends, we know you went through almost a spiritual Holocaust, but you survived. You immigrated to Israel. You are here with us. Let’s not erase everything from your past. Let’s open the door for you to come closer and feel part of the Jewish people.”

Rif also shared her family’s excitement ahead of the holiday. “My kids haven’t slept for a week. There’s huge excitement. The house is decorated, everyone is preparing, and ‘Grandfather Frost’ already bought all the presents,” she said. “My 8-year-old son already says, ‘Mom, you’re lying. There is no Grandfather Frost. You’re the ones buying the gifts.’

“The food is Soviet food. Of course, in Israel we also do an al fresco barbecue,” she said. “My parents are here with us, and we show them that their story matters and is meaningful. My children are growing up in three cultures and languages. I speak Hebrew with them, their father speaks English because he comes from an English-speaking home, and their grandparents speak Russian. They respect and love all three. That’s the State of Israel I would like to live in in 2026.”

When it comes to children, is it still necessary to explain Novy God to teachers and preschool staff?

“I thought not. I was naive,” Rif said. “But when my child entered first grade at a so-called progressive Tel Aviv school, there were still parents who, when I suggested celebrating Hanukkah together with Novy God, didn’t understand why we needed to celebrate a Christian holiday. To everyone’s credit, once I explained and told the story, today every year it has become a ‘Hanukkah-God’ event, and we celebrate together with love. There is a lot of unfamiliarity, and the duty to dispel that ignorance wherever possible falls on us, Russian-speaking Israelis. Not to give up. People often tell me, ‘Alex, why do you try to explain? Who cares? If someone doesn’t want to, that’s their problem.’ But it matters, because in the end our children experience racism and hatred in educational settings. If we don’t explain, they’ll take it straight in the face.”