Ashkenazi selichot, Jewish penitential prayers recited before the High Holidays, have historically attracted less attention than their Sephardic counterparts, partly because many of the Ashkenazi poems were written during the Crusades at the end of the 11th century, according to Mishael Vaknin, a scholar and author who has dedicated years to researching selichot and High Holiday prayers.

“Honestly, who wants to read today about people being killed, slaughtered and massacred? Who wants to read about weeping, suffering and pogroms when we live here in a free and safe Israel? All of this felt distant until October 6,” Vaknin said.

“On October 7, we all woke up to a nightmare. That day, my sons were called up for reserve duty, and I remembered the opening poem of the Ashkenazi selichot, ‘How Shall We Begin Here,’ written during the Crusades. It describes exactly what happened to us on October 7. In other words, it is still relevant and unfortunately, history repeats itself.”

Vaknin’s new book, Selichot Tour – Part II, focuses on Ashkenazi selichot and continues the work of his previous volume, published before the war. The book features essays by thinkers, cultural commentators and scholars, including Rabbi Shai Piron, former Israeli Education Minister, Rabbanit Rachelle Fraenkel, and Rabbanit Dr. Michal Tikochinsky. Supreme Court Vice President Noam Sohlberg wrote the foreword, contrasting divine judgment with human law.

“I told all the contributors: ‘The audience for this book spans readers of Haaretz to readers of Makor Rishon. I want both groups to feel comfortable reading it,’” Vaknin said.

Historical and cultural differences

Ashkenazi selichot are markedly different from Sephardic ones, which are often lyrical and almost joyous. “Rabbi Shai Piron writes beautifully on this in the new book. Ashkenazi selichot come from a consciousness of awe and fear, while Sephardic selichot come from love. We need both. Selichot are a relatively late custom. The earliest records date to the 10th century. They are not a halachic obligation. The Shulchan Aruch calls them ‘a beautiful custom.’ As a custom, there was room for innovation and additions,” Vaknin said.

The earliest selichot in the Babylonian community appear with Rabbi Saadia Gaon, or slightly earlier with Rabbi Amram Gaon, Vaknin said. By the 11th century, Jewish communities began composing their own selichot. In Spain, during the Golden Age, poets wrote from a context of flourishing rather than persecution. Abraham ibn Ezra’s Lech Eli Teshukati is an almost erotic poem exploring the human relationship with God. In the anonymous poem Ben Adam Mah Lekha Naramad, the poet writes, “Seek forgiveness from the Lord of Lords,” as if demanding absolution.

“In contrast, Ashkenazi poets like Benjamin ben Zerach, writing during the Crusades, describe people being killed, slaughtered and massacred. Rabbi Shmuel HaKohen of Mainz composed Malachei Rachamim, appealing to angels to persuade God to have mercy. Shortly afterward, he, his wife and children were killed by Christian raiders during the First Crusade. Reading these poems after October 7, I felt they described exactly what happened in Be’eri, the Gaza border villages and Sderot,” Vaknin said.

He stressed the importance of preserving this heritage, which reflects the reality of communities that endured pogroms and persecution. “Otherwise, in a generation or two, Ashkenazi selichot may only survive in Haredi enclaves,” Vaknin said.

Music, fear and reverence

Ashkenazi selichot feature fewer melodies and many poems are recited quietly in a whisper. In Sephardic tradition, even children may take solo lines. “In Ashkenaz, the cantor takes center stage and the congregation is largely passive. In Sephardic tradition, everyone participates,” Vaknin said.

Sephardic communities begin selichot on the first of Elul while Ashkenazi communities start only a few days before Rosh Hashanah and finish in under half an hour. Sephardic services can last over an hour. “Ashkenazi selichot are unique to each day, often recited only once a year and without melodies they are harder to remember. You read the text and think it’s irrelevant until a catastrophe like October 7 reminds you even 900-year-old words remain relevant,” Vaknin said.

He added that the month of Elul in the Ashkenazi, especially Lithuanian, world is perceived as a time of judgment. Rabbi Israel Salanter, founder of the Musar movement, said even the fish tremble in Elul. “There is an atmosphere of awe and fear, very different from the Sephardic experience,” Vaknin said.

Preserving the tradition

Although Vaknin comes from a Sephardic background, Ashkenazi selichot are not foreign to him. “I knew the Ashkenazi selichot since ninth grade at Or Etzion Yeshiva. The work on the new book involved deep research to understand the context, allusions and ancient manuscripts,” he said.

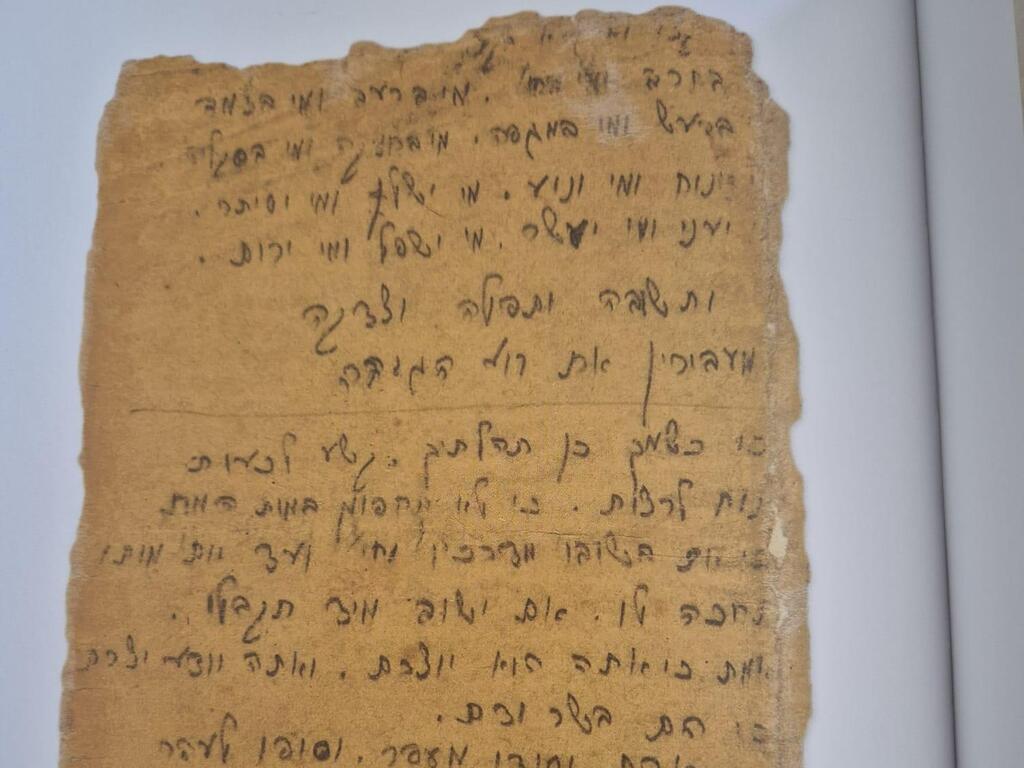

One manuscript featured in the book is V’Netane Tokef, central to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur prayers. It belonged to Naftali Stern, a cantor from Satmar, Transylvania, deported to Auschwitz with hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews. Stern’s wife and four children were murdered and he survived forced labor at Wolfsberg camp. Before Rosh Hashanah, with prayer books confiscated, Stern wrote selichot and prayers on torn cement sacks, which he used throughout the Holocaust and later in Israel. He eventually donated the sacks to Yad Vashem for preservation.

Vaknin said he wanted to present Sephardic and Ashkenazi poems together. “I don’t want to bring people back to religious observance. I want to preserve the heritage of selichot of all of Israel,” he said.

Modern adaptations and music

Alongside the book, two music albums record the selichot, featuring cantor Yitzhak Meir and graduates of Yeshivat Hesder Yeruham, ten of whom fell in the war, produced by Yair Harel. Vaknin said he approached Meir to help preserve Ashkenazi selichot. “He was enthusiastic and we spent almost two months in the studio recording all the poems, even those without traditional melodies. Some were set to Sephardic tunes,” he said.

The project culminated in a launch performance combining Sephardic and Ashkenazi selichot, performed by the Jerusalem Piyut Ensemble, Yitzhak Meir, cellist Maya Belsitzman and singer Odeya Azulay, known as Odeya. The recording will be the fifth album of the project, officially released on September 28 at Reading 3, Tel Aviv Port.

Vaknin said the cross-pollination is vital. “I hope we’ll eventually have an Israeli prayer book combining selichot traditions. Already there are synagogues singing Sephardic poems to Ashkenazi tunes and vice versa. This, to me, is wonderful,” he said.

He added that seeing selichot in popular culture, such as the adaptation of Ben Adam Mah Lekha Naramad by Odeya, is meaningful. “It helps preserve this culture. Prayer and selichot are part of our cultural heritage. If we fossilize them, we become irrelevant. Experiencing them traditionally and in new forms keeps their depth and consciousness alive and that’s what matters,” Vaknin said.