In the Talkback Beit Midrash

“In addition to the issue of women’s singing, we would love to see an article by you on women’s head covering, the halakhic discourse that evolved from the story of Kimhit in the Talmud, and how it was blown out of proportion, just like this issue.”

So wrote, last week, a friend who goes by the ambitious pseudonym ‘El Ehad’ (One God). With pleasure. Thank you for the challenge. Thanks to you, today we meet Kimhit, the woman with the surprising name, reminiscent of kemach, flour in Hebrew, who carries on her shoulders a significant portion of the propaganda surrounding women’s head covering.

They performed hafrashat challah on Kimhit

The story of Kimhit gained popularity and appeared in many versions. Originally, however, it was not propaganda for head covering but a critical, even mocking tale about the priestly class. Over time, proponents of head covering took this critical story, kneaded its sanctimonious elements, and created a sticky dough that simply will not come out of our hair.

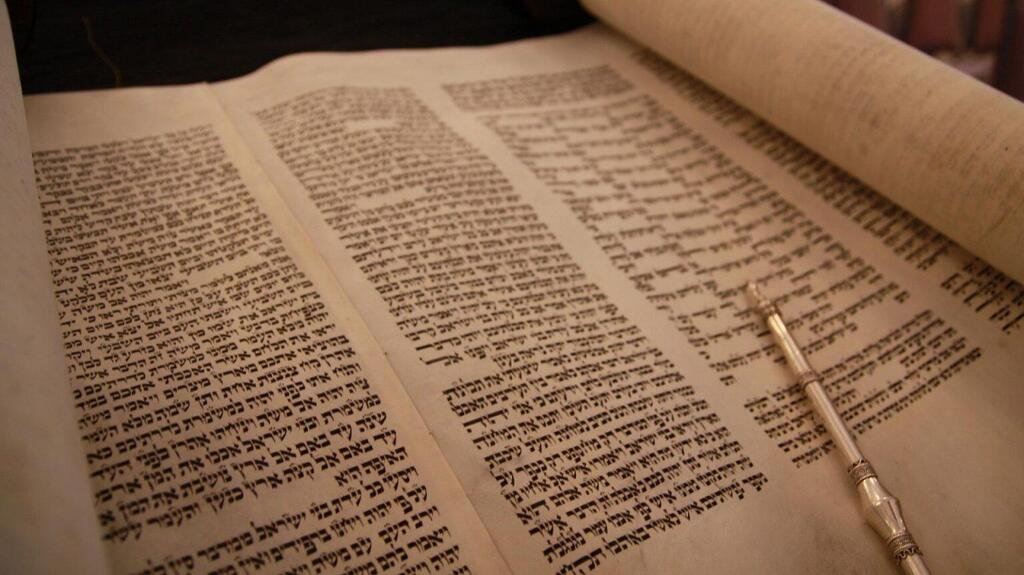

Here is one version of the legend (Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Yoma 47a):

“They said of Rabbi Ishmael son of Kimhit: Once he conversed with an Arab in the marketplace, and a spray of saliva from his mouth fell upon his clothes, rendering them impure. His brother Yeshevav entered and served in his stead, and their mother saw two High Priests in one day.

And again they said of Rabbi Ishmael son of Kimhit: Once he went out and conversed with a certain ruler in the marketplace, and a spray of saliva from his mouth fell upon his clothes. His brother Joseph entered and served in his stead, and their mother saw two High Priests in one day.

Seven sons had Kimhit, and they all served as High Priests. The Sages said to her: What have you done to merit this? She said to them: Throughout my days, the beams of my house never saw the plaits of my hair. They said to her: Many have done so, and it did not avail them.”

Kimhit, the mother of seven distinguished sons, lived during the Second Temple period. She was the mother of a High Priest, and through a nearly impossible sequence of events, she merited seeing all her sons serve as High Priests. Why nearly impossible? Because, in principle, the High Priesthood was a lifetime appointment.

This could have been a nightmare story

For Kimhit to see all seven of her sons serve as High Priests, she would have had to bury six of them. Are we dealing with a variation on the story of Hannah and her seven sons? The narrator chooses a different path, not a tragic one, but the path of temporary impurity.

From the story, we learn that Ishmael was Kimhit’s firstborn and the permanent High Priest. Occasionally, Ishmael would go out to converse in the marketplace with foreigners. During these encounters, saliva from the stranger’s mouth, whether an Arab, a ruler, or in parallel versions a king, would land on Ishmael’s garments, rendering him suspected of impurity and requiring a replacement.

After the “saliva conversation” with the Arab, Yeshevav served as temporary High Priest. After the encounter with the ruler, Joseph replaced him. We must assume this happened four more times, allowing Kimhit to see all seven of her sons serve.

A bit disgusting

True, this is not a tragic story, but it is hardly a pleasant one. It is a legend steeped in saliva, and that is no coincidence. The Sages were the rivals of the Priests, and the destruction of the Temple marked their bitter victory. After the destruction, the Priests lost power, and the Sages established themselves as the alternative leadership. They spared no effort in mocking the priesthood and what it represented.

Any mother who educates her children properly can hope to see them become Torah scholars, since in theory anyone can achieve that status. In contrast, becoming High Priest requires either tragedy or farce. The story of Kimhit ridicules the very notion of priestly prestige.

I imagine a Friday night dinner at the Kimhit household. The children plan a surprise for their mother. According to the scheme, Ishmael goes out every week to chat with some stranger in the marketplace and returns each time with the same announcement: “The stranger spoke and spat. I may have become impure.” One brother after another steps in, and their mother proudly watches all her sons serve as High Priests, ready to boast to the neighbors.

What have you done to merit this?

The Sages, feigning astonishment, ask Kimhit: “What have you done to merit this?” She replies: “Throughout my days, the beams of my house never saw the plaits of my hair.” Over generations, the “rabbis of head covering” seized on this line and spread the message: If you want to take pride in your sons, hide your hair. In parallel versions, Kimhit adds that even the hem of her robe was never seen.

Here is where suspicion sets in. Why would a woman need to maintain modesty before the walls and beams of her own home? How, exactly, is she meant to comb her hair or get dressed? This is not modesty. It is madness. The sages of the Mishnah and Talmud are not generally portrayed as sanctimonious or obsessed with extreme stringencies, certainly not such absurd ones.

The suspicion deepens when we recall why her sons became High Priests in the first place. Ishmael became impure again and again. A mother so obsessively modest should have raised children meticulous about ritual purity, yet it is repeated impurity that brings her honor. In our version, the Sages puncture her claim: “Many have done so, and it did not avail them.” It was not modesty that produced High Priests, but impurity. In other versions, Kimhit is praised without irony.

Thank God for context

The editor of this Talmudic passage places, just a few lines earlier, another tradition, even more outrageous, about Ishmael son of Kimhit:

“They said of Rabbi Ishmael son of Kimhit that he could grasp four kavs in his handfuls, and he would say: ‘All women planted a shoot, but my mother’s shoot reached the roof.’”

If this sounds crude, you are reading it correctly. High Priests were required to grasp incense in their hands, and a kind of “handful competition” emerged. Ishmael, blessed with unusually large hands, boasts about them and, like a devoted mama’s boy, compliments his mother.

For those who missed the point, the Talmud later explains: Ishmael is speaking about semen. And for those still unsure: all women, he claims, found men with weak seed, but his mother found one whose “shoot rose to the roof.”

Do we still want to hold Kimhit up as a model of modesty?

Back to head covering

I have not surveyed all the sources on head covering. For those impatient, here is the bottom line: there is no biblical mandate, and only a handful of scattered Talmudic references. The story of Kimhit, read sanctimoniously, has become a central educational tool in the service of head covering.

I do not criticize women who choose to cover their hair. Let each woman decide for herself. My criticism is aimed at moral preaching, intimidation, distributing headscarves at the Western Wall, and the endless mansplaining about the “wonderful sons” we will supposedly bear if we hide our hair, even from the beams of our own homes.

Food for thought

Why do religious soldiers leave a hall when a woman sings, but not when a woman with uncovered hair is present? Because the first exclusion has gained legitimacy, while the second has not yet. If we continue to concede to demands to exclude women’s voices from public space, the next demand will be to exclude women with uncovered hair from that same space.

First published: 12:26, 01.25.26