The threshold of the house is not good

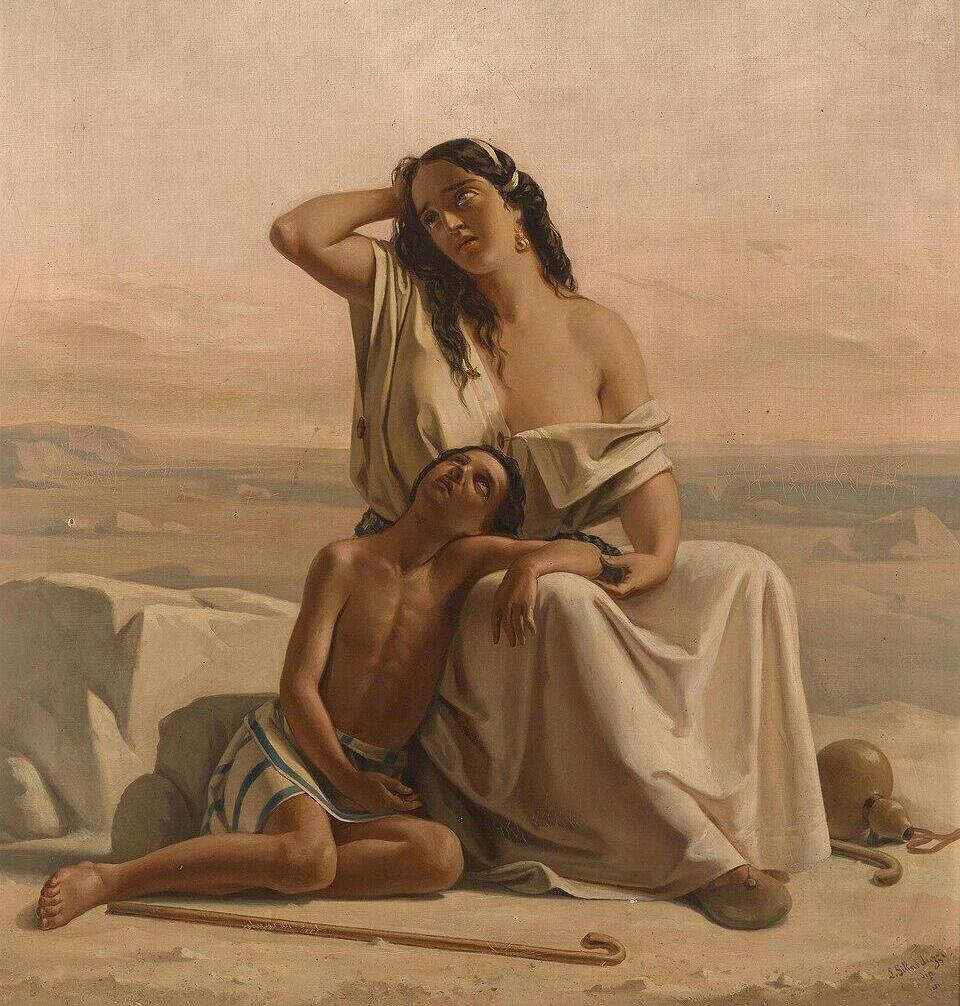

Sometimes I find myself muttering: "The threshold of the house is not good." An ancient code which, according to the Midrash, was devised by Abraham to signal to his son, Ishmael: "You have chosen an unsuitable partner; keep away." It is quite ironic to think that Abraham, who banished Ishmael and Hagar to die in the desert, feels entitled to criticize his son’s wife. We will return to that irony later, but I want to start with a simple admiration for this delicate code phrase that has seeped into everyday language. There are times when I look at my own life, or the life of a close friend, and I just know: "The threshold of the house is not good."

Your son whom you loved, Ishmael

Abraham is a man of binding. He banished Hagar and Ishmael to the desert, bound Isaac and, at the end of his life, sent away the sons of the concubines. There is no way to sugarcoat this pill, but the Midrashim try.

Some recount that Abraham’s true love was Hagar, and all his life he yearned for the mother and son he had banished to the desert ("banishing and weeping"—a familiar syndrome). And here is the legend (Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer, Chapter 30):

"Ishmael sent and took a wife from the plains of Moab, named Aisha. After three years, Abraham went to see his son Ishmael, swearing to Sarah that he would not dismount from his camel where Ishmael dwelt. He arrived at midday and found Ishmael's wife there. He asked her: 'Where is Ishmael?' She said to him: 'He and his mother have gone to bring dates from the desert.' He said to her: 'Give me a little bread and a little water, for my soul is weary from the desert journey.' She said to him: 'There is no bread and no water.' He said to her: 'When Ishmael comes, tell him these things, and say to him that an old man from the land of Canaan came to see you, and said that the threshold of the house is not good.'

When Ishmael came, his wife told him this matter, and he sent her away. And his mother sent and took him a wife from her father's house, named Fatimah. Another three years passed, and Abraham went to see his son Ishmael, swearing to Sarah as before that he would not dismount from the camel where Ishmael dwelt. He arrived at midday and found Ishmael's wife. He asked her: 'Where is Ishmael?' She said to him: 'He and his mother have gone to graze the camels in the desert.' He said to her: 'Give me a little bread and water, for my soul is weary from the desert journey.' She brought it out and gave it to him… And when Ishmael came, his wife told him this matter, and Ishmael knew that his father's mercy was still upon him… After Sarah's death, Abraham returned and took back his divorcee."

A similar version exists in Muslim tradition. The Islamic influence on the legend is evident, particularly in the women's names: Aisha (appearing in various variations), Muhammad's beloved wife, and Fatimah, his beloved daughter. The "Islamic nature" of the legend helps date Pirkei De-Rabbi Eliezer to the 8th century CE.

The threshold of the house is ironic

The irony cries out. The story of the angels’ visit turned Abraham into a model of hospitality, and ostensibly, his criticism of Aisha, who distances him from his son and denies him even bread and water, is understandable. However, the bread and water immediately remind us of the banishment of Hagar and Ishmael: "And Abraham rose up early in the morning, and took bread and a bottle of water, and gave it unto Hagar, putting it on her shoulder, and the child, and sent her away: and she departed, and wandered in the wilderness" (Genesis 21:14).

One could see Aisha as the one exacting Ishmael's revenge. Aisha holds the anger that Ishmael does not allow himself to feel, and in this sense, the "threshold of the house" is actually good. In Jungian terms, we might say that Ishmael is alienated from his shadow. Ishmael, banished by his father to the desert, cannot acknowledge his rage toward him, so he separates from the woman who held and symbolized that anger. In her place, Hagar brings him a new wife, Fatimah, who in Muslim tradition is considered a saint and a model of piety, generosity and simplicity. In the Midrash before us, Fatimah represents the reconciliation with the Superego, with the religious demand for generosity and submission to the patriarch. It is not surprising that the Fatimah of the Midrash was brought by Hagar, the woman who remained loyal to the man who banished her.

Abraham’s true love

Sarah, who is portrayed even in the Bible as jealous and vengeful, knows that "Ishmael" is merely a cover name for "Hagar", her husband's true love. Therefore, she does not permit Abraham to dismount from his camel during his visits to Ishmael. The legend concludes with the announcement that, after Sarah’s death, Abraham took Hagar as his wife. Now it becomes clear why Abraham needed to banish Ishmael’s first wife. In order to marry Hagar a second time, Abraham had to organize a supportive home court. He could not contend with the Shadow, with the rage over the banishments and the bindings. The woman who held the rage of the banishment for the family was herself banished. With her expulsion, Abraham's sins were forgotten, and he was invited with kingly honor into the home of Hagar, Ishmael and Fatimah.

The threshold of our house is not good

From almost every angle we view Israel of 2026, we are forced to say that "the threshold of the house is not good." So many men and women have been murdered; there are countless battle-scarred souls, invisible to all; families destroyed; many families displaced from their homes who have not yet returned; the North and the South have not been rehabilitated; the police force has been captured by a racist minister; the leadership is corrupt and decadent, and the opposition is non-existent. Yet, amidst all this "I shall believe in humanity" we have a magnificent civil society, compassionate and fighting. It is the justification for our effort to stay, to repair, and to raise ourselves from the ruins.

2 View gallery

Protest in Habina square, calling on police to stop the murders in Arab society

(Photo: Aviv Atlas)

We stood with Aisha

Abraham, Sarah, Hagar, Ishmael and his two wives, and Isaac, can learn to live together. Not with lies and pretenses, but out of a decision that the long years we have shared have destined us for this. Aisha, the banished woman of the legend, is the pivotal figure; she is the Shadow with which we must learn to live, the difficulties, the fears, the historical reckonings, the open wounds and the scars between Judaism and Islam, that exist alongside many years of kinship and cooperation.

On a recent Saturday night I stood with tens of thousands of Arabs and Jews, calling on the police to halt the bloodbath in Arab society. Since that demonstration, at least seven more Arab citizens have been murdered. With black shirts and flags, and signs in Arabic and Hebrew, we stood in the heart of Tel Aviv. The chants on the megaphones and the speeches on stage were in both languages, while the tears and the rage needed no language. I feel sorrow for anyone who did not get to participate in this demonstration (and I feel doubly sorry because I know they will have further opportunities). It was a rare and empowering experience of human solidarity and shared destiny, of an insistence on living together in a way we have not lived until today; to place life at the center and politics in its appropriate margins.

The late Ahmad Khair Diab

During the demonstration, I saw a young man holding a stack of posters, unsure of what to do with them. I asked him for one picture, and others joined me; the stack emptied quickly, and images of a handsome young man, no longer among the living, were hoisted high. Every few minutes, relatives of Ahmad approached me and told me about a wonderful young man who lived in Tamra, studied accounting at the Hebrew University, and in 2024 got married and was murdered. His father, they recounted, is a restaurant owner and businessman who refused to pay protection money to criminals.

When Ahmad returned from his honeymoon, he was shot; 20 days later, he succumbed to his wounds. His mother received the diploma Ahmad had labored for, but never lived to see. I hugged Ahmad’s sister and promised her that I would remember and remind others of her brother, a handsome, smart and good man who was murdered because no one demands justice for the blood of the Arab sector. May his memory be a revolution.

First published: 16:12, 02.09.26