Benny Wexler, an ultra-Orthodox Israeli with foreign citizenship who has traveled to more than 100 countries, including hostile and dangerous places such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Sudan, recently made a secret visit to Beirut’s Dahiyeh district, the stronghold of Hezbollah.

Fearing discovery, Wexler took extreme precautions to conceal his Israeli identity. “From the moment I realized I was flying to Beirut, the fear kicked in. I couldn’t sleep at night and had to take medication for the headaches,” he said. “I booked my flight through an American travel agent so my Israeli IP address wouldn’t be detected.”

He replaced his phone, hid his credit cards inside his shoes, and packed his tefillin in a plain bag with no Hebrew markings. Entering Beirut was the most stressful part, he recalled. “They checked every person for several minutes. All the tourists were from Iraq, Kuwait or Jordan — not a single one from the West. I stood out.”

According to Wexler, immigration officials seemed to suspect something when they noticed his passport listed Be’er Sheva as his birthplace. “The officer called a supervisor, and they started discussing me,” he said.

Visiting Hezbollah territory

“When I realized I was actually in Lebanon, I had to pinch myself,” Wexler said. Once inside, he discovered that 90,000 Lebanese pounds were worth just one U.S. dollar. “I hadn’t prepared a driver or hotel because I didn’t believe I’d make it in,” he said. “After entering, I booked a hotel and took a cab there.”

His hotel was not far from Dahiyeh. He befriended staff members to help him find a driver who could take him to Jewish sites, a synagogue and a cemetery, while keeping his identity hidden. Eventually, he met a driver named Mohammed, who realized Wexler was Jewish but didn’t object. “I have nothing against Jews,” Mohammed told him. “I’ll drive you for $70 a day, including taking photos.” Wexler visited the Jewish cemetery, founded in 1829 and home to some 4,500 graves. Located on the border between Christian and Muslim neighborhoods, the cemetery was heavily damaged during Lebanon’s civil war. “A wall recently collapsed there, and renovations are ongoing,” he said.

He met a senior member of Beirut’s tiny Jewish community, who cautiously tested his identity before accompanying him to the cemetery and warning him not to take photos. “He grew up in Lebanon and has never visited Israel — he’s forbidden to. His fear was enormous, and he advised me to leave immediately,” Wexler said.

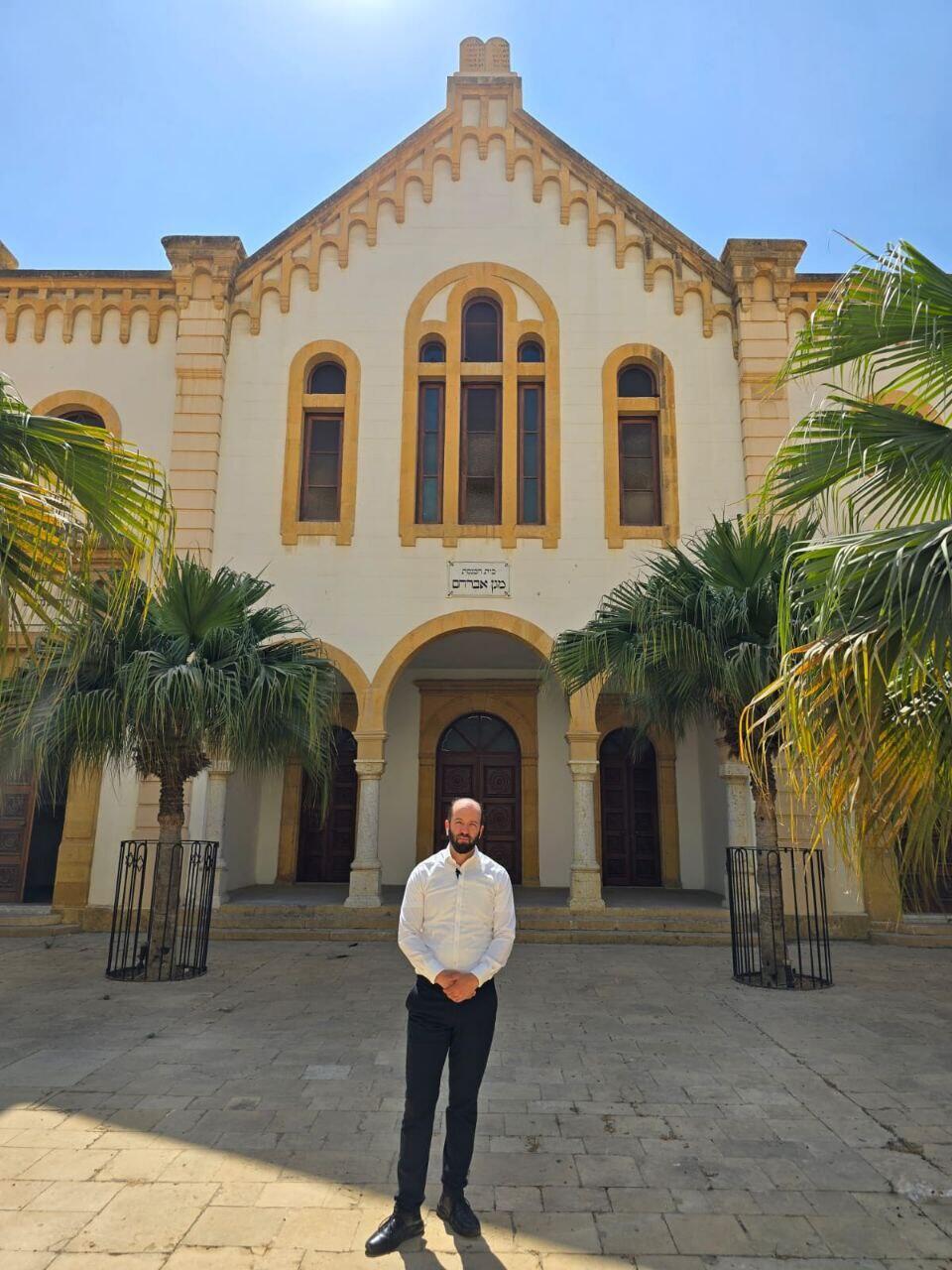

At Maghen Abraham Synagogue, the only one left in Beirut, Wexler obtained police permission to enter. The synagogue stands in the upscale Wadi Abu Jamil neighborhood, once home to about 20,000 Jews. “Only the synagogue remains,” Wexler said. “It suffered theft and damage, and the port explosion nearly destroyed it. The rabbi was deeply moved to see me.”

Wexler also toured other landmarks, including the Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque and the restored Beirut Port. During the trip, his driver surprised him by expressing admiration for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, calling him “the Churchill of our time who saved the Middle East from terror.”

He also explored Lebanon’s Jeita Grotto and the ancient cities of Byblos and Jbeil. But his visit to Dahiyeh, Hezbollah’s stronghold, was the most nerve-racking. “Everyone warned me not to go there. No taxi driver wanted to take me,” he said. “Luckily, my driver knew the area well. I saw destroyed buildings and countless posters of Hassan Nasrallah on the walls.”