In the 1950s, the State of Israel, through Yad Vashem, defined the term ‘Righteous Among the Nations’, an honor that has since been awarded to more than 28,000 people. They were non-Jews who saved Jews during the Holocaust. But what about Jews who saved Jews? Was it an obvious moral duty, or should those who risked their lives to rescue others, even members of their own people, receive special recognition?

In recent years, awareness has grown around honoring Jews who saved Jews. Even without formal recognition by Yad Vashem, the term ‘Jewish rescuer’ has gained traction. Since 2000, an annual ‘Jewish Rescuer Citation’ ceremony has been held at the initiative of the B’nai B’rith organization. To date, the award has been presented to more than 650 people.

Aryeh Barnea, former chairman of the Amcha association, a member of Yad Vashem’s directorate, a Holocaust lecturer and chairman of the committee that decides on awarding the Jewish Rescuer Citation, explains that “the issue of Jews saving Jews appeared occasionally in Yad Vashem ceremonies and commemorations. But their view was that it is challenging to determine who helped whom and in what way, and that doing so could unfairly exclude or stigmatize many people who are not formally recognized as rescuers or heroes. Another argument was that help by a Jew to another Jew is expected and self-evident, while a non-Jew who helps a Jew is the true hero.”

So what has changed in recent years?

“Personally, as a university lecturer on the Holocaust, I thought differently,” Barnea says. “Not as opposition to Yad Vashem, but as someone engaged in the subject. My message was that a Jew whose life was already in danger, and who knowingly took on additional risk to help strangers, is a great hero. This, of course, does not detract from the heroism of the Polish or Greek rescuers who saved Jews.”

How are the criteria for awarding the honor determined?

“The committee for awarding the Jewish Rescuer Award was established in 2000 by Holocaust survivor Chaim Roth in partnership with B’nai B’rith, and clear working methods and criteria were set,” Barnea explains. “One principle is that the information must come from multiple sources, not just the testimony of the person themselves.

"Beyond that, it must involve someone who took on additional mortal danger beyond that already faced as a Jew under Nazi rule or that of their allies and collaborators, and who made an effort to save other persecuted Jews who were not family members.

Aryeh Barnea, Holocaust researcher and Jewish Rescuer Citation committee's chairmanCourtesy

Aryeh Barnea, Holocaust researcher and Jewish Rescuer Citation committee's chairmanCourtesy“There were cases where we received requests to grant the title to Jews who were involved in rescue efforts at the time from New York, Tel Aviv or Switzerland, and we rejected those requests. We sent a letter of appreciation to the requesting families, acknowledging that everything was done for a good and important purpose, but only those who truly risked their own lives can receive the award.”

3 View gallery

The mime artist Marcel Marceau, among the rescuers whose stories are featured

(Photo: Keystone / Getty Images)

Barnea says the committee receives inquiries constantly. So far, 650 awards have been granted and several dozen applications have been rejected. “The burden of proof lies with the applicant, and sometimes we ask for additional documentation,” he says. “There are people who are hurt that their grandfather did not receive the award, but that is the price of regulations and orderly, value-based work.”

The world’s first institution dedicated to the subject

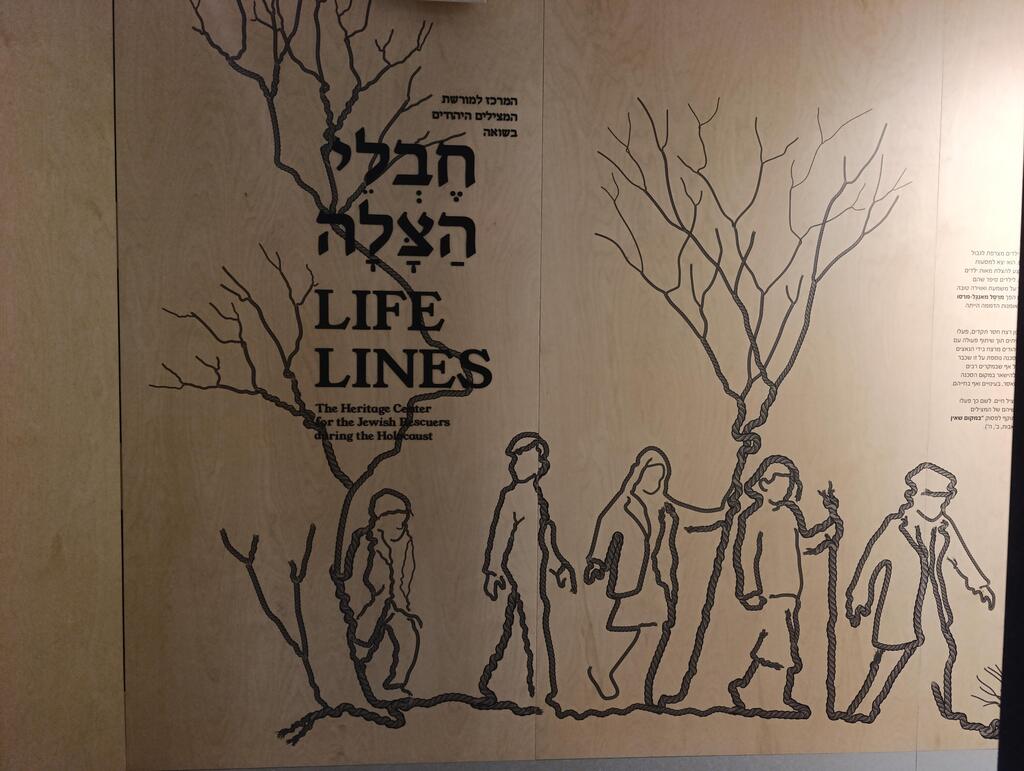

These days, the Jewish rescuer project is taking another step forward and gaining a physical presence with the opening of the ‘Hevlei Hatzala’ - Life Line Heritage Center, operating within the Wilfrid Israel Museum of Asian Art and Studies at Kibbutz HaZore’a in northern Israel.

“Wilfrid Israel, after whom the museum is named and who bequeathed his unique collection to the kibbutz, saved many Jews during the Holocaust, so it was a natural connection,” Barnea says. “We built a special structure within the museum that honors the rescuers and presents the stories of 10 prominent Jews who saved Jews. This is essentially the first place in the world dedicated to the topic.”

Among the stories presented are those of renowned mime Marcel Marceau, who led children on foot to safety in Switzerland; Fanny Ben Ami, who rescued 30 children in France; and Naftali Backenroth-Bronicki, a Polish Jewish agronomist who employed Jews and thus prevented the Nazis from sending them to camps.

Also featured are the stories of David Gur, who forged documents that helped save Jews in Hungary, and that of Jewish lawyer Hélène Cazès-Benatar, whose actions in Morocco were defined as a one-woman rescue enterprise after she saved many Jews.

3 View gallery

The Jewish rescuers whose stories are presented at the museum

(Photo: Courtesy of the museum)

Beyond documenting the stories and honoring the rescuers, what do you see as the mission of this museum?

“Of course it is important that the public knows about the heroism and the stories, and that the rescuers and their families receive recognition,” Barnea says. “But in my view, the primary goal is to educate about the value of human life and the continuity of the Jewish people. We want to teach about the exemplary paths taken by rescuers during the Holocaust.”

Nurit Asher-Fenig, the museum’s CEO, adds that “the ‘Hevlei Hatzala’ heritage center was established as an integral part of the Wilfrid Israel Museum of Asian Art at Kibbutz HaZore’a because Wilfrid Israel was the first Jewish rescuer and perhaps the greatest in terms of the scope of his rescue efforts. The museum’s management sees it as essential to highlight the inspiring story of Wilfrid and all the Jewish heroes of the Holocaust period, whose stories are almost unknown.

“I invite the wider Israeli public to come to the museum and provide testimonies, even indirect ones. We ask for the public’s help. We want to uncover and research the phenomenon of rescue during the Holocaust and to preserve this important narrative of salvation for future generations as well.”

She notes that the Life Line Center was established in cooperation with the Committee to Recognize the Heroism of Jewish Rescuers During the Holocaust (JRJ), curated by Ronit Lusky and Shir Meller Yamaguchi, and designed by Studio Present under the direction of Nadav Hazut. The center was made possible through generous donations from private donors and support from the Estates Committee.