Jews have long recorded their lives, beliefs and daily affairs in writing. Because Jewish communities lived for centuries in many parts of the world, they developed several Hebrew-based languages, including Judeo-Arabic, which blends Hebrew and Arabic, and Judeo-Greek. Writing styles also changed from region to region and from era to era. Specialists can often tell when and where a manuscript was written by studying the shape of its letters.

In recent years, the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society, and later the National Library of Israel, a major cultural and research institution in Jerusalem, worked to scan Hebrew manuscripts from libraries and private collections worldwide. These scans were uploaded to the library’s online portal “Ktiv,” a central database for digitized Hebrew manuscripts.

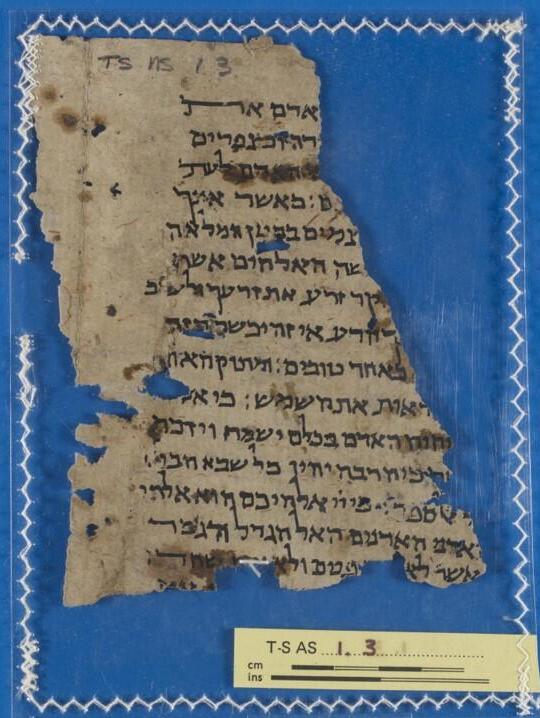

The Ktiv site includes thousands of images from the Cairo Genizah, considered the largest and most diverse collection of medieval Jewish manuscripts. A genizah is a storage place, usually in a synagogue, for worn-out or damaged texts that contain the name of God and therefore cannot be discarded. The Cairo Genizah was preserved for centuries in the attic of the Ben Ezra synagogue and other locations in Cairo, Egypt.

The collection is a unique time capsule of Jewish life in Cairo and of Jewish communities across the Mediterranean and beyond that were in contact with it. It contains religious writings, personal letters, legal documents, business records and poems. Yet most of it has remained accessible mainly to scholars. Less than a third of the roughly 400,000 fragments have been cataloged, and fewer than 10 percent currently have transcriptions.

A new project aims to change that by enabling automatic transcription of the vast photographic archive of the Cairo Genizah and similar manuscript collections. Using advanced artificial intelligence, the project can do in minutes what manual transcription would take researchers years to complete. Once transcribed, the texts will be searchable online and available to readers worldwide.

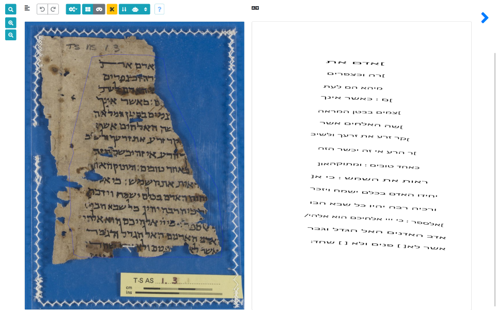

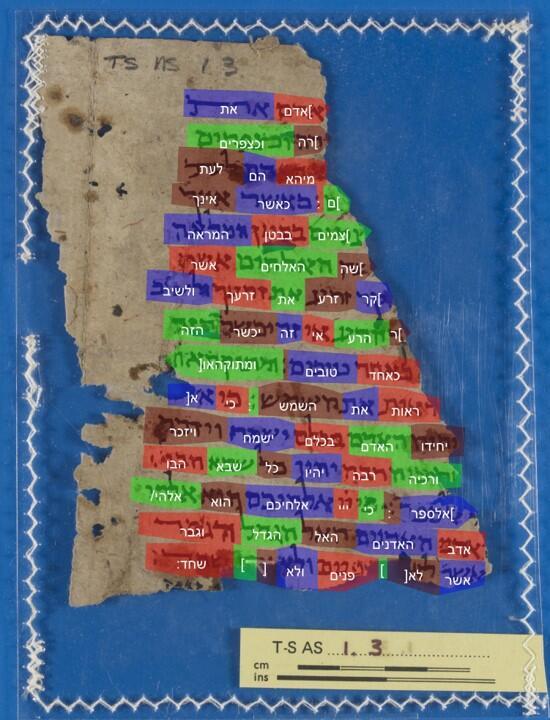

7 View gallery

Text-line detection with automatic transcription beside the page

(Photo: Daniel Stoekl, Ktiv Project)

For decades, scholars believed that computers could not reliably read handwritten historical manuscripts. Optical character recognition, or OCR, works well on printed pages, but handwriting is far more variable. Many Genizah texts are faded, torn or written in multiple hands, making them especially difficult to decipher.

That hurdle began to fall in 2023, when the European Research Council awarded a 10 million euro grant to MiDRASH, short for “Movements of textual and written traditions through large-scale computational analysis of medieval manuscripts in Hebrew script.” One of the project’s core goals is an accurate automated system that can transcribe Hebrew-script manuscripts and allow anyone to run detailed searches across them.

7 View gallery

Entrance sign at the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo

(Photo: Aleksandra Tokarz/Shutterstock)

Over the past two years, MiDRASH researchers have built automated image analysis and transcription models using eScriptorium, an open-source platform designed for turning manuscript images into text. Early results show the system can produce transcriptions with a high level of accuracy. Once the work is completed, the Cairo Genizah transcriptions will be added to Ktiv, expanding the database into a fully searchable global resource.

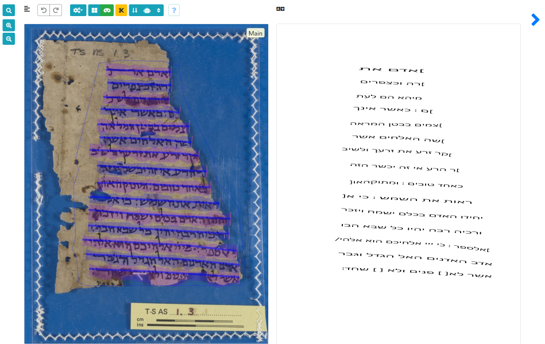

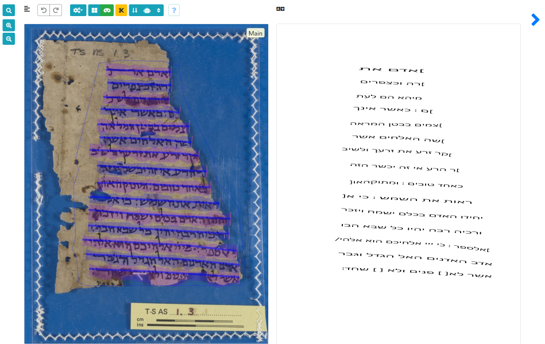

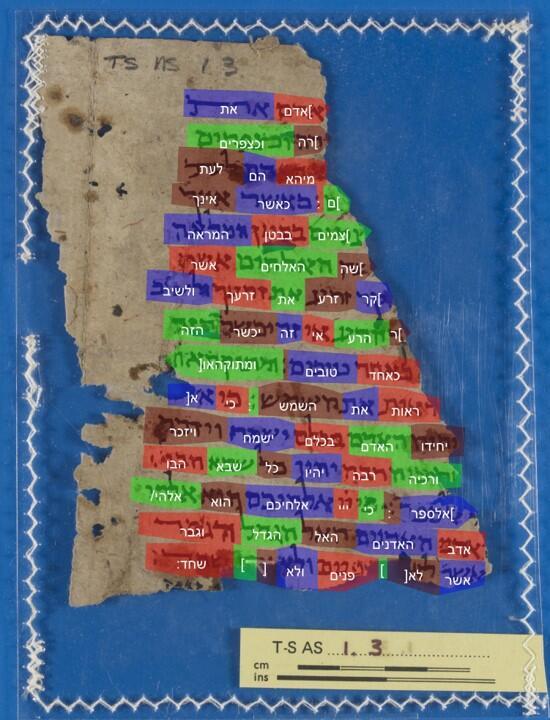

7 View gallery

Displaying the text as it was automatically generated on the page

(Photo: Daniel Stoekl, Ktiv Project)

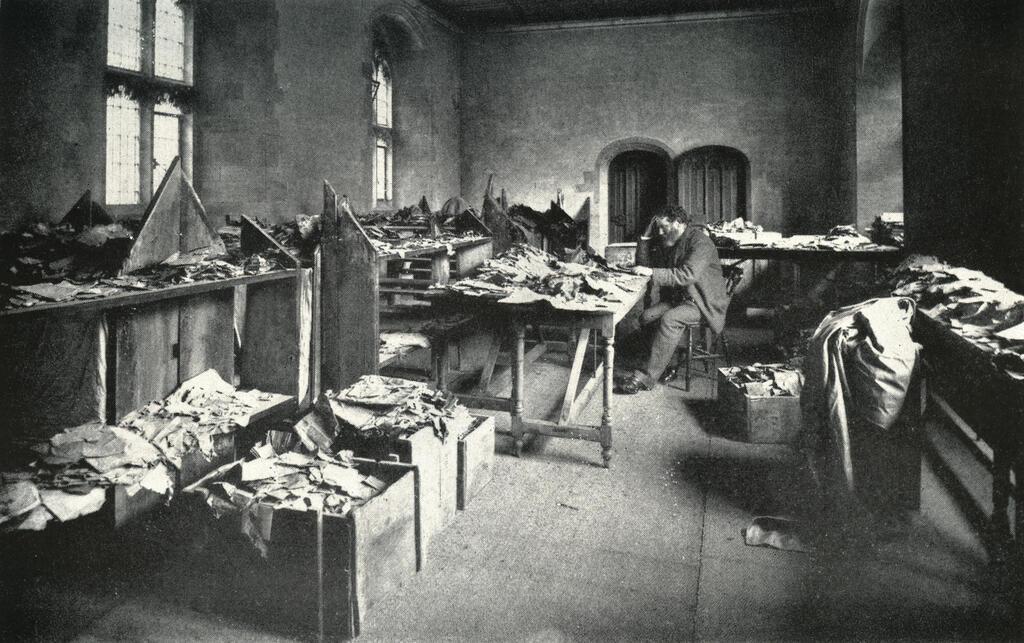

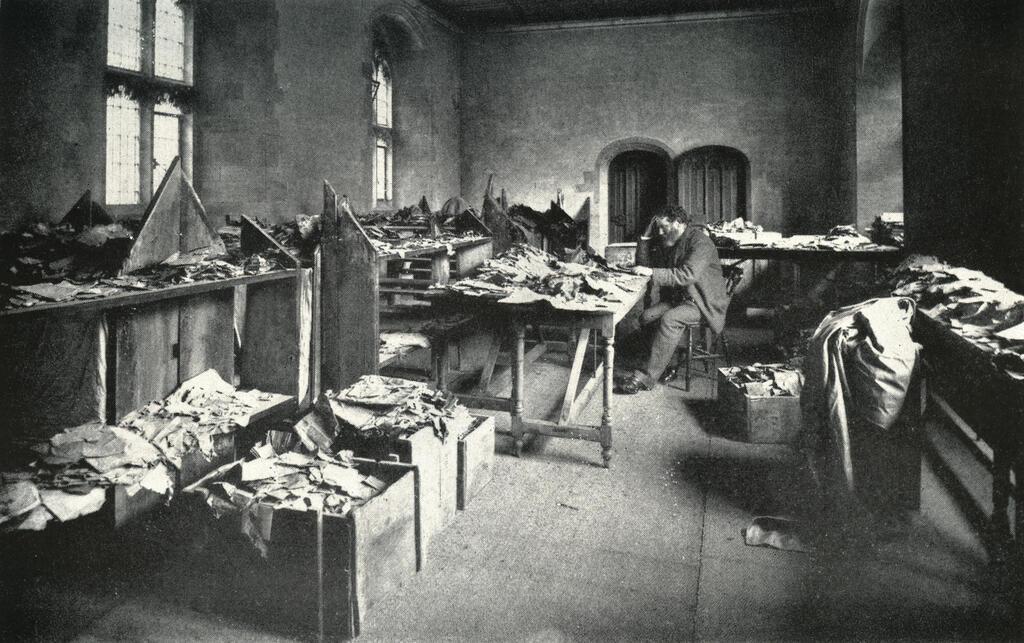

7 View gallery

Rabbi Shneur Zalman HaCohen Schechter, also known as Solomon Schechter, studies the Cairo Genizah

(Photo: Bridgeman Images/Reuters)

Initial findings from the Cairo Genizah analysis will be presented Monday, Nov. 24, from 10 a.m. to 11 a.m. at the National Library of Israel. Three of MiDRASH’s four principal researchers will speak. They are Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra, professor of ancient Hebrew and Aramaic at the Paris School for Advanced Studies; Nachum Dershowitz, professor emeritus in computer science and artificial intelligence at Tel Aviv University; and Dr. Avi Shmidman, senior lecturer in Hebrew literature at Bar-Ilan University and a senior researcher at DICTA, the Israeli Center for Text Analysis. The fourth principal researcher is Prof. Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, president of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies.

Dr. Tsafra SiewPhoto: Lens Productions

Dr. Tsafra SiewPhoto: Lens ProductionsDr. Tzafra Siew, the National Library’s project manager for digital humanities, said MiDRASH is transforming the study of medieval manuscripts. By combining machine learning with the library’s digitized collections, she said, tasks that once required years of painstaking work can be done quickly and at scale. Researchers will be able to identify individual scribes, track how texts traveled between regions and ask new kinds of questions about the past. In practical terms, she said, hidden links between documents will come to light and many manuscripts that have never been deciphered will gain new meaning.

The system works in stages. It first identifies where the text appears on a page and separates it into lines. Each line is then transcribed as a whole, because recognizing any letter depends on surrounding letters within a word and sentence. Human reviewers check a portion of the results, correct mistakes and feed those corrections back into the model to improve its learning. Later, another automated correction pass is carried out using natural language algorithms. “This will be done for each writing style, with the final goal of covering every type of Hebrew script used in the Middle Ages,” Siew said.

A public “transcription-thon” will take place at the National Library in Jerusalem and online from Nov. 24 to Nov. 27, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. The event will focus on medieval manuscripts written in flowing Hebrew script. Participants will review and correct automated transcriptions with full guidance provided throughout.