A new study has found that it is possible to identify different writing styles in the Bible based on the frequency of specific words and linguistic patterns. The research, conducted by the University of Haifa in collaboration with Reichman University, was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

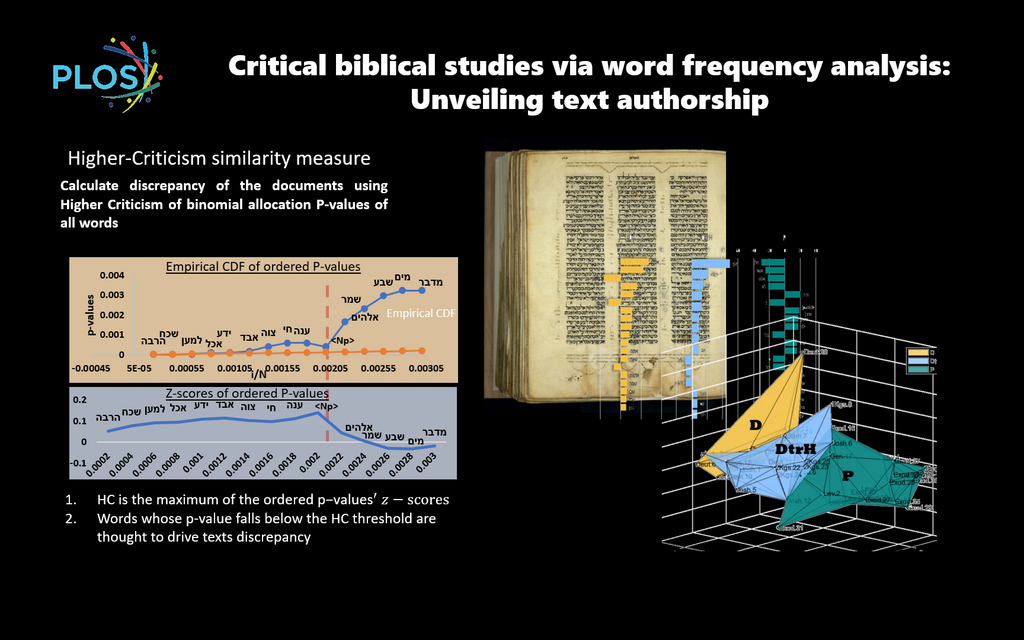

Using an innovative approach that combines artificial intelligence with statistical tools, the researchers were able to distinguish between three well-known biblical writing groups: early texts in the Book of Deuteronomy; the texts in the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings); and priestly writing, found mainly in Leviticus and other sections of the Torah.

According to the researchers, their method can attribute additional biblical chapters to one of these writing groups, even when the identity of the author is unknown.

“We found that each group of writers had a different linguistic fingerprint—even in common words like ‘not,’ ‘which,’ or ‘king,’” said Prof. Israel Finkelstein, head of the School of Archaeology and Maritime Cultures at the University of Haifa and one of the study's authors. “The method we developed can detect those differences with precision. This is a new scientific tool that lends empirical support to ideas that, until now, were based mainly on interpretation—and it could reshape how we understand the Bible’s development.”

The question of who wrote the Bible, and under what historical circumstances, has preoccupied biblical scholarship for more than 200 years. It is widely accepted among scholars that the Bible was written over a long period by various authors in different locations, sometimes incorporating multiple versions of the same story. But despite decades of detailed literary analysis, there was no computational, data-driven method to systematically and objectively examine these differences—until now.

The research team, which included Dr. Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin (Duke University), Dr. Alon Kipnis (Reichman University), Axel Bôhler (Faculty of Protestant Theology, Paris), Eli Piasetzky (Tel Aviv University), Prof. Thomas Römer (Collège de France), and Prof. Finkelstein, set out to determine whether biblical writing styles could be identified through a computational, objective method that avoided subjective assumptions or manually selected keywords.

In the first stage of the study, the team developed a model that analyzed the frequency of individual word roots and word root combinations (such as pairs or triplets of adjacent roots) across the biblical text. They then tested the model on 50 chapters from the Bible’s first nine books, which had already been categorized by biblical scholars into the three writing groups. “The model compared the chapters based on linguistic usage patterns and offered a quantitative method for assigning each chapter to a specific writing style,” said Dr. Faigenbaum-Golovin.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

In the second phase, the researchers applied their model to additional chapters whose writing style has been disputed in the academic literature. “The goal was to see whether the method could be used for discovery—to identify the writing style of chapters without scholarly consensus,” said Prof. Römer.

Among the tested texts were the stories of the Ark of the Covenant (in 1 and 2 Samuel), the Book of Esther, sections of Proverbs, chapters from the patriarchal narratives in Genesis (concerning Abraham and Jacob), and parts of Chronicles. Each chapter was statistically compared to the three writing groups, and the model assessed whether attribution was possible and which group it most closely resembled.

The findings suggest that biblical writing style can indeed be identified through vocabulary and phrase patterns—even in relatively short texts. “One of the main advantages of the method is its ability to explain its own conclusions by pointing to the specific words or expressions that led to a chapter’s classification,” noted Dr. Kipnis.

The researchers emphasized that the main goal of the method is to reconstruct the linguistic and cultural characteristics of writer groups who operated in different times and places. “The Bible was formed over centuries and in various settings—some in Jerusalem, others during the Babylonian exile. The ability to detect the linguistic features of each group helps us better understand how the biblical text evolved,” they concluded. The new method is expected to become a valuable tool for biblical scholars, linguists, and historians of ancient texts, and may eventually assist in analyzing other ancient writings beyond the Bible.