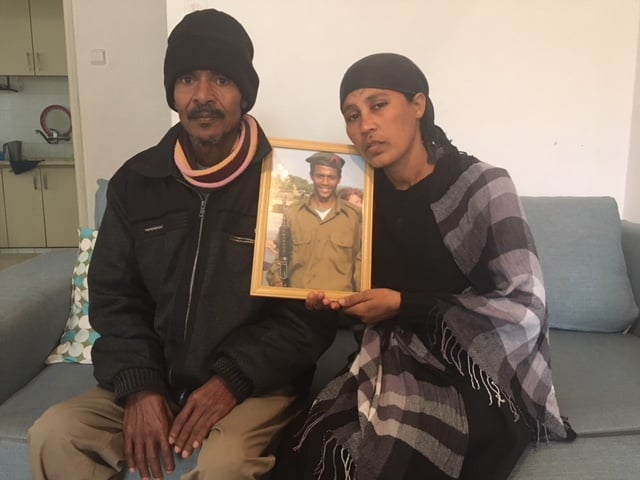

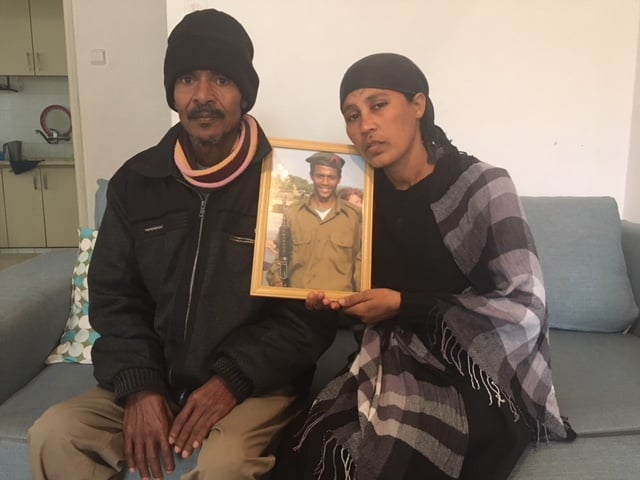

In the living room of their cozy rented apartment in the central city of Lod, Ethiopian immigrants Atalay and Mamey Biadga share fond memories of their son, Yehuda.

Mamey cries.

“Yehuda was a tsaddik,” she says, speaking through an Amharic interpreter she uses the Hebrew word for righteous person.

7 View gallery

Atalay and Mamey Biadga sit in their Lod living room with a picture of their son, Yehuda, who was killed a year ago by police

(Photo: Tara Kavaler)

“He always cared about people and he always cared about me. When I came in from outside, he stood up. When I told him it was too much, he said a son who does not respect his mother and father does not respect God,” she says.

“He didn’t deserve to die so early,” she says. “I have no explanation for the bad way he passed from this world, and I still can’t really believe it.”

On January 18, 2019, a police officer in Bat Yam, a coastal city just south of Tel Aviv where the family lived, shot and killed 24-year-old Yehuda, who, according to his family, was suffering from mental illness.

The police say Yehuda was holding a knife in his hand and that the officer who shot him was acting in self-defense. Eyewitnesses, however, say the officer was in no imminent danger.

When asked whether the officer was still on the job and whether he had faced any punishment, an Israel Police spokesman responded via email: “Don’t know.”

Yet according to several sources, including Tzachi Lasry, the Biadgas’ lawyer, he remains on the force to this day, which has devastated the family.

Says Mamey: “We know that people who kill a cat or a dog go to jail. So the life of a person, the life of my son, is worth less than the life of a cat or dog? … There is no justice for Yehuda or for us.”

According to Lasry, the case against the policeman was closed last May. He says the officer was never interviewed after killing Biadga, and that eyewitnesses who disagreed with the claim of self-defense were never called.

“They did not give any substantial evidence or address the contradictions in the case, especially not the police officer’s version,” he says. “Arriving at the truth did not interest them at all.”

When contacted, the Israel Police Department of Internal Affairs, which is actually part of the State POffice, responded: “The decision was made that there was no criminal offense in this case because… the victim had run into close range… with a knife pointed outward in a deliberate manner toward the upper part of [the officer’s] body. [The officer] was in immediate danger and therefore legally was allowed to use his weapon.”

Shula Mola, an educator, board member and former chairperson of the Association of Ethiopian Jews, believes the fact that Biadga was of Ethiopian origin played a role in why the police officer was let off the hook.

“They chose to protect the policeman because the killer is their person [while] Yehuda was a poor Ethiopian,” she says. “I think that if he had been someone else, of a different a color and from a different socioeconomic status, it would probably be different.”

Biadga was the first of two Ethiopian-Israelis killed by police officers in 2019. His death led to a mass march that shut down a major highway skirting Tel Aviv.

After 19-year-old Soloman Tekah was killed in July – by an off-duty police officer – thousands of protesters blocked main roads throughout the country over several evenings, burning trash bins and even vehicles before being pushed back by police teargas and batons.

Mola insists that the deaths of Biadga and Tekah highlight the systemic challenges that Ethiopian-Israelis face, arguing that the discrimination started when they first arrived, and that it remains enshrined in policy.

There are close to 150,000 people of Ethiopian origin living in Israel today. The bulk were brought from Ethiopia in secret missions such as Operation Moses in the mid-1980s, and Operation Solomon in 1991.

“Policies have pushed us into a bad place, into bad neighborhoods,” she says. “Don’t people know there is a connection between housing and opportunities in life? From my perspective, the root of the policy is racism.”

7 View gallery

The Ethiopian community protests following the shooting of Yehuda Biagda

(Photo: AFP)

She points out that Ethiopian-Israelis earn less than any other Jewish demographic group in the country.

“The government thinks we are different,” Mola says. “We come from Africa, and for them [Israeli officials], it’s enough for us to just be here. They don’t expect more from us than to be cleaners and to remain at a lower socioeconomic level.”

Dr. Avraham Neguise, a former Knesset member for Likud and a past chairman of the Knesset Committee for Immigration, Absorption and Diaspora Affairs, agrees.

“In the workplace, Ethiopian-Israelis are discriminated against in numerous ways,” he says. “There are many who are not given job offers or are unable to advance in their current position due to stereotypes.”

According to data from the government’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Ethiopian-Israeli women earn just 50% of the average net salary of Israelis. What’s more, Ethiopian-Israelis who have successfully completed university degrees are over-represented in low-wage jobs.

While there is an anti-racism department at the Justice Ministry that is supposed to address the discriminatory practices and institutional racism that Ethiopian-Israelis, among other demographic groups in Israel, face, Mola believes it lacks teeth. She adds that the racism her community feels today is “not [confined to] one specific thing. It’s a lot of specific things that happen again and again and again.”

Another way Ethiopian-Israelis face racism is through police profiling.

In 2018, young members of the community accounted for 5.4% of all minors arrested, while Ethiopian-Israelis make up just 1.7% of the population.

“When you take a step back and look at everything as whole,” Mola says.

“We see different patterns that should push us to ask: Why is there strong over-policing? Why is it normal that police officers tend to stop people of dark color, especially males?”

And then there is the matter of the way police open fire.

“Just last year, two Israelis of Ethiopian origin were killed,” Mola says, referring to Biadga and Tekah. “People should question this. If we know that the percentage of Ethiopians adults fired [upon] is much higher than other Israeli averages, [we should] at least question it!”

7 View gallery

The Ethiopian community protests following the shooting of Yehuda Biagda

(Photo: AFP)

Atalay Biadga says through an interpreter that his son Yehuda’s name in Amharic meant happiness.

“He was very, very kind and mature. Even when he was a kid, he behaved like an adult. He respected everyone. When Yehuda sat on the couch and I came from outside the house, he stood up,” he says, referring to a sign of respect in Ethiopian culture that is displayed by one’s son-in-law, not son.

“I tell myself he was a perfect son because he knew his life was short and he wanted to be this kind of person,” Atalay says.

Neguise argues that in the year since Biadga died, the plight of Ethiopian-Israelis has only worsened.

He notes, for example, that despite a government promise to bring to Israel 1,000 immediate-family members who remained behind in Ethiopia, only 600 were brought.

“It’s very sad that this existing government is discriminating against the immigration of Ethiopian Jews,” he says. “There has not been any improvement in the last year for the community. [The situation] has actually gotten worse.”

Mola believes that what took place after the July death of Tekah – rioting as well as ongoing protests at police stations and outside the homes of top police and justice officials – led authorities to take a harder line with the off-duty officer who killed him.

“It made the decision-makers recommend the prosecution of the policeman,” she says.

Yet like Neguise, she is not at all satisfied.

“Any cop who has beaten or killed Ethiopian-Israelis,” she says, “has yet to be convicted.”

For Mola, the focus should remain on demonstrations rather than meetings with bureaucrats, who, she believes, are fully aware that only legislation can help.

“We don’t want to be fooled again by officials who say they will fix things and [then] don’t change anything,” she says. “There’s nothing to discuss. Leaders need to go to work to correct their practices and their biased perceptions about Ethiopian-Israelis.”

Just last month, activists in Jerusalem regrouped. They decided to continue their efforts toward the establishment of an independent committee to investigate police violence against Ethiopian-Israelis. They also plan to hold a march from the Justice Ministry to the national police headquarters, and to start an information campaign as well.

“We want to educate people so they become part of the fight to change society,” Mola says. “We live here. We are in our country and we want our rights to be fully realized.”

Nonetheless, Atalay and Mamey Biadga’s lives remain shattered.

“We moved from our house [in Bat Yam] to this rental [in Lod] because every place in Bat Yam reminded us of Yehuda,” Mamey says.

“The school reminded us of Yehuda. Every corner reminded us of Yehuda. It was too difficult. I can’t work anymore. I’m at home all day, and no one asks us what’s happening to us. It is this that disappoints me more than anything,” she says.

“Yehuda will never come back to us,” Mamey says. “The only thing I want is that people should know how the government, which has a responsibility for its citizens, didn’t do anything about Yehuda. They killed him and don’t care, and I know it’s about color.”

To this day, no Israeli leader has visited the Biadga family.