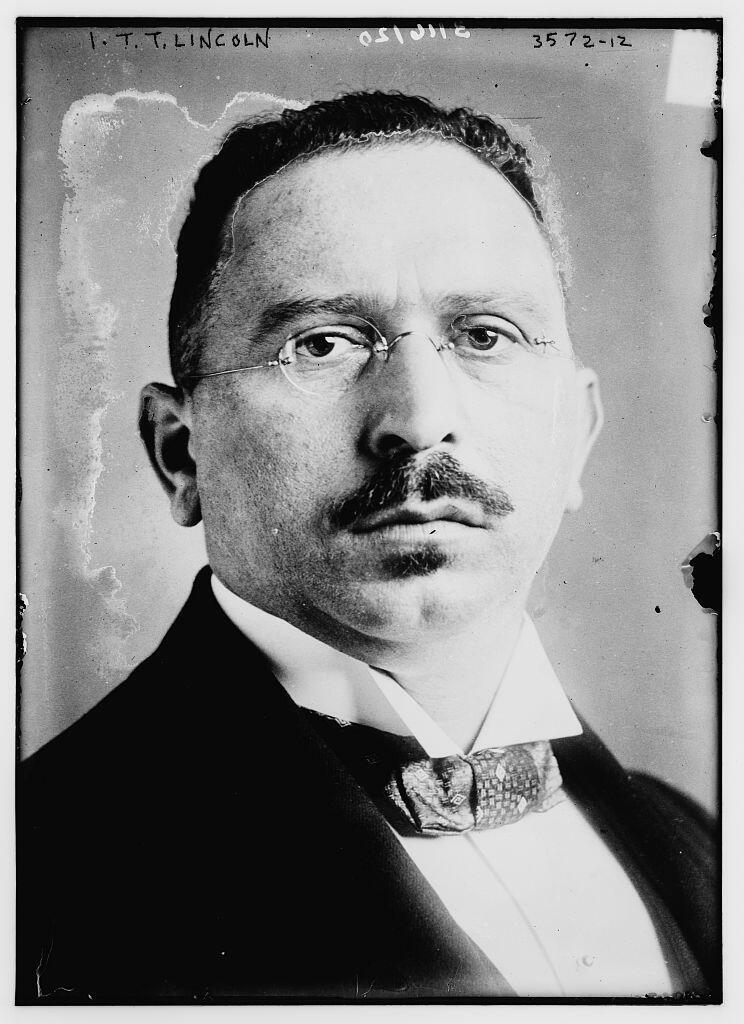

Few figures of the early 20th century lived as many lives, crossed as many borders or embraced as many contradictions as Ignatius Timothy Trebitsch Lincoln, a Hungarian-born adventurer and convicted con artist whose career took him from the British Parliament to Nazi circles, from espionage to Buddhist monasticism, and ultimately to a mysterious death in wartime China.

Born Ignác Trebitsch on April 4, 1879, in the Hungarian town of Paks, he was raised in an Orthodox Jewish family that later moved to Budapest. His father, Náthán Trebitsch, was originally from Moravia. From an early age, Trebitsch displayed both ambition and instability. After leaving school, he enrolled in the Royal Hungarian Academy of Dramatic Art, but his studies were cut short by repeated encounters with police over theft and fraud.

In 1897, facing legal trouble, he fled Hungary and settled in London. There, he encountered Christian missionaries and converted from Judaism, a step that would mark the beginning of a lifelong pattern of ideological reinvention. Baptized on Christmas Day in 1899, he trained at a Lutheran seminary in Germany before being sent to Canada as a missionary to Montreal’s Jewish community, first under Presbyterian sponsorship and later Anglican. His missionary efforts were largely unsuccessful, and disputes over money led him back to England in 1903.

By 1904, he had legally changed his name to Trebitsch Lincoln and pursued a clerical career within the Church of England. With the support of influential figures, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, he became a curate in Kent. Soon after, he entered politics through his association with Seebohm Rowntree, a prominent Liberal Party figure. With Rowntree’s backing, Trebitsch Lincoln ran as the Liberal candidate for the Darlington constituency and won a stunning victory in the January 1910 election — despite not yet being a British citizen.

His political success was short-lived. Members of Parliament were unpaid at the time, and Lincoln’s chronic financial problems deepened. He lost his seat later that year and failed to secure reelection. His parliamentary career collapsed, and he drifted into a series of failed business schemes across Europe, including attempts to profit from Romania’s oil industry.

As World War I loomed, Lincoln offered his services to British intelligence as a spy. Rejected, he approached Germany instead and briefly worked as a double agent. His incompetence and unreliability soon became apparent, and he fled again — this time to the United States. In New York, he sold his story to the press, publishing revelations about espionage activities and later releasing a memoir, Revelations of an International Spy.

Embarrassed by the publicity, the British government hired the Pinkerton agency to track him down. He was extradited to England on fraud charges, convicted and sentenced to three years in prison. During his incarceration, his British nationality was revoked. Upon release in 1919, he was deported and effectively rendered stateless.

Penniless, Trebitsch Lincoln resurfaced in postwar Germany, embedding himself in extreme right-wing nationalist circles during the chaotic early years of the Weimar Republic. He became associated with figures such as Wolfgang Kapp and Erich Ludendorff and played a role in the failed Kapp Putsch of 1920, briefly serving as press censor for the insurgent government. During this period, he met Adolf Hitler, who arrived in Berlin shortly before the coup collapsed.

After the putsch failed, Trebitsch fled through Austria and Hungary, aligning himself with a loose network of monarchists and reactionaries known as the White International. Entrusted with the group’s archives, he sold the documents to foreign intelligence services. He was tried for treason in Austria but acquitted and deported yet again.

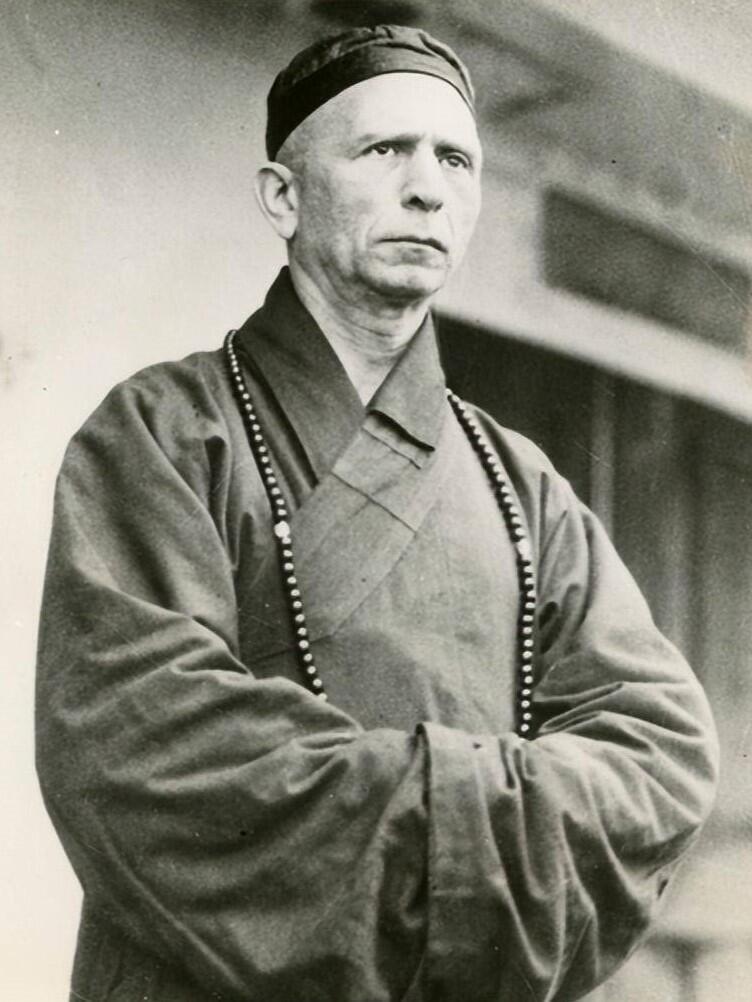

By the late 1920s, Trebitsch had arrived in China, where he worked for several regional warlords, including Wu Peifu. There, he underwent another transformation, converting to Buddhism following what he described as a mystical experience. Taking the name Chao Kung, he became a monk and later an abbot, founding a monastery in Shanghai. Followers were required to surrender their possessions to him, and accounts from the period describe authoritarian rule, abuse and the collapse of the community.

In the 1930s, Trebitsch aligned himself with Imperial Japan, producing anti-British propaganda and cultivating ties with Japanese authorities. After the outbreak of World War II, he sought renewed relevance by offering his services to Nazi Germany, proposing to mobilize Buddhists across Asia in support of the Axis cause. The plan gained brief interest, including from Gestapo officials in the Far East, before unraveling when his Jewish origins became known.

Supported by Japanese officials, Trebitsch went further, proclaiming himself the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama following the death of the 13th Dalai Lama. The claim was rejected by Tibetan authorities and failed to gain legitimacy.

Trebitsch Lincoln died in Shanghai on Oct. 6, 1943, officially of stomach illness, at the age of 64. Some contemporaries later suggested he may have been killed on orders from German authorities, though definitive evidence has never emerged. A biographer who attended his funeral later wrote that he suspected the coffin was empty.

Historians describe Trebitsch Lincoln as a consummate impostor — a man whose intelligence, charm and theatrical instincts allowed him to navigate institutions and ideologies he neither understood nor believed in. His life intersected with many of the most violent and transformative events of the 20th century, leaving behind a trail of deception, betrayal and shattered relationships.

Today, he remains a cautionary figure — less a believer in any cause than a reflection of how instability, ambition and chaos can converge in a single life, with consequences that ripple across nations and decades.