It sounds like a fantasy today, but there was a time when Iran stood by Israel and helped ensure its energy security. From the founding of the state, Israel faced difficulties securing reliable oil supplies, largely due to the Arab League's embargo and its repeated demands from international companies to cut all ties with Israel.

The Soviet Union initially provided oil to Israel, but, under pressure from Arab countries, following the 1956 Suez War, broke its contracts with Israel.

Beginning in 1957, after the Suez War, and continuing until 1979, Iran emerged as Israel’s savior, alongside Mexico and Norway, providing regular shipments of oil. There were only minor disruptions in 1973, the year of the Yom Kippur War.

But Israel’s energy lifeline from Iran came to an end when the Shah was overthrown, and Ayatollah Khomeini came to power.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The 1973 war also marked the beginning of a broader global energy crisis. In retaliation for Western support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, Arab countries imposed an oil embargo that sent shockwaves across the globe.

A headline in Yedioth Ahronoth on Nov. 4, 1973, read: "The Arabs gather to decide: who will get oil — and who won’t.

Saudi Arabia, a pioneer in the oil war, has already declared it will stop supplying oil to any country that transfers fuel or its byproducts to the United States. Fuel prices in America have soared, and shortages are casting a shadow over the upcoming Christmas season.

U.S. airlines are cutting flights, and the Air Force has canceled training operations. European Common Market nations are meeting to adopt a position."

12 View gallery

Nov. 4, 1973: "The Arabs gather to decide: who will get oil — and who won’t.

(Photo: Archive, Yedioth Ahronoth)

On Nov. 21, another headline reported: "Common Market countries appear ready to supply the Netherlands with oil ‘under the table.’ European foreign ministers, meeting in Copenhagen, have drafted a new position on the Middle East crisis, details of which remain confidential.

Arab diplomats in The Hague stated: ‘We will show mercy to the Netherlands if it makes clear that it opposes the Zionists’ policies of occupation, torture and Nazi-like extortion.’

The Saudi oil minister added: ‘We are not extortionists, but if the Europeans want Arab oil, they must pressure the United States and Israel.’" The Arab outrage toward the Dutch stemmed from the Netherlands’ outspoken support for Israel.

On Nov. 22, Saudi King Faisal told an Egyptian newspaper that he had informed U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger: “President Nixon must declare support for an Israeli withdrawal. The oil embargo will remain in place until the Palestinian and Jerusalem issues are resolved."

By Dec. 10, 1973, facing shortages resulting from the Arab oil embargo, West Germany announced it would ban Sunday driving.

A dramatic headline on Dec. 16, 1973, declared: “Night of Extortion in Copenhagen.” Reporter Ali Cohen wrote from the Danish capital: “Four Arab foreign ministers, who invited themselves to the Danish city during the summit of 'European Market' countries, kept their hosts waiting until 3 a.m., then warned: ‘There will be no oil until Israel withdraws.’”

The summit concluded with a 'balanced' declaration, ensuring economic aid for Arab nations, coupled with acknowledgment of Israel’s security needs and a caution to Arab states not to overplay their oil weapon.

On Dec. 18, 1973, a headline echoed contemporary concerns: “Also the USSR to cut fuel use. The reason: a desire to meet growing oil demands from buyer states. Moscow feared that the Arab embargo could cripple European industry and delay the delivery of essential machinery to the Soviet Union."

Who could have predicted then that nearly 50 years later, Russia would again find itself at the center of a similar geopolitical storm, this time from the opposite side.

A more optimistic report came on Dec. 26: “Europe and Japan welcome loosening of Arab oil embargo. But rising fuel prices will demand deep cuts.”

On March 14, 1974, a report announced: “Arab oil states to lift embargo on U.S.; Official statement expected in three days from Vienna.”

The March 19 headline marked a sigh of relief in Washington: “U.S. expects a reduction in gasoline lines. Washington satisfied but avoids comment on end of Arab embargo.”

On March 24, 1974, the headline noted that columnists Evans and Novak wrote that 'French Foreign Minister encouraged Syria to oppose lifting the oil embargo.” Indeed, on March 27, Syria lashed out at Egypt: 'We were left alone in the fight.' Syria’s vice president demands the embargo on the U.S. be reinstated."

Some Arab states realized that the oil embargo could boomerang, harming their own economies in the long run. Yet, they struggled to find a compromise in their conflict with Israel.

On Sept. 23, 1974, King Faisal declared: “We do not want to reinstate the oil embargo, but our friends must understand where their interests lie. All we ask is that Israel vacate all occupied Arab territory and restore full national rights to the Palestinian people, including control over Jerusalem, a holy city for Islam."

On Nov. 18, 1974, U.S. President Gerald Ford warned that the legitimate interests of the Palestinian people could not be ignored. “The situation in the Middle East is delicate and complex,” he said. “It cannot continue indefinitely. A new military conflict in the region could trigger another Arab oil embargo."

12 View gallery

Gerald Ford: The legitimate interests of the Palestinian people could not be ignored

(Photo: Archive, Yedioth Ahronoth)

The following day, Nov. 19, a more optimistic tone emerged. The U.S. Treasury secretary declared, 'The energy crisis is easing. Recent oil discoveries and greater coordination among oil-consuming nations may force the Arabs to lower prices.”

On Dec. 3, 1974, headlines revealed that Kuwait had acquired a 14% stake in Mercedes-Benz. A German spokesperson commented that the deal had its benefits: if Arab oil magnates invested in the German economy, they would be less inclined to harm it with another oil embargo.

On Feb. 6, 1975, U.S. Senator Charles Percy was quoted as saying, “The oil problem is the key to peace in the Middle East. Another war in the region would deal a serious blow to the U.S. economy.”

On Feb. 11, 1975, it is reported that the Shah of Iran reassured the world: “There will not be another oil embargo, and if there is, it will not be effective, because Iran will not join.”

12 View gallery

Shah of Iran: “There will not be another oil embargo

(Photo: Archive, Yedioth Ahronoth)

At the time, Iran and Israel still enjoyed strong relations, four years before Ayatollah Khomeini’s rise to power in February 1979. Nine days earlier, on Feb. 2, 1975, the Shah had stated clearly: “Israel will receive oil, but will have to pay for it."

Devastating consequences alongside positive change

The 1973 Arab oil embargo had devastating consequences in many countries. Global supply contracted dramatically, demand surged, and prices soared, first by dozens of percentage points, later by hundreds.

The embargo plunged much of the world into one of the most severe recessions in modern history. Transportation in Western Europe and North America nearly ground to a halt. Tens of thousands of factories were forced to close, unable to function without fuel. Major corporations went bankrupt. In cold European countries, many households could not afford to heat their homes.

Significant shifts reshaped the global economy. Large cars sat unused, while small, fuel-efficient models became highly sought-after and were sold at very high prices. Japanese fuel companies thrived, while major American firms struggled. The world slid into a deep recession marked by a rare combination of inflation and economic stagnation, what economists call stagflation.

Yet the crisis also spurred progress. Major oil consumers began seeking alternatives, including nuclear energy, green technologies, and renewable sources.

Oil and gas exploration in the North Sea expanded significantly and ultimately reduced the threat of oil being used as a geopolitical weapon in the future.

In addition, smaller oil-producing nations outside the Arab world, which at the time controlled roughly 60% of global oil output, ramped up production and built ties with countries looking to diversify their energy sources.

Oil exploration campaigns expanded, and early signs of natural gas deposits were discovered in the North Sea and elsewhere.

One of the most consequential developments was the establishment of massive strategic oil reserves in countries worldwide, led by the United States.

Around the same time, the International Energy Agency was founded by major energy-consuming nations to coordinate global energy data and policy.

In the meantime, in Israel, prices surged, and cars sat idle

The oil embargo also hit Israel hard, affecting daily life.

On Jan. 14, 1974, Yedioth Ahronoth reported: “As fuel prices rise, electricity, transportation, and water costs have also gone up. Economists predict the consumer price index will increase by 3% to 4%. Fuel prices alone rose by about 50% overnight.” That spike makes today's recent price rises seem modest in comparison.

Thus, electricity and water rates soared by dozens of percentage points within a year.

On Jan. 15, 1974, the headline read: “Special ministerial committee expected to approve increase in residential electricity rates. A 40% to 50% rise is likely, and consumption limits may be lifted.”

In contrast, a more recent proposal to raise electricity prices by 5.7% was scaled back to 3.4% after public outcry.

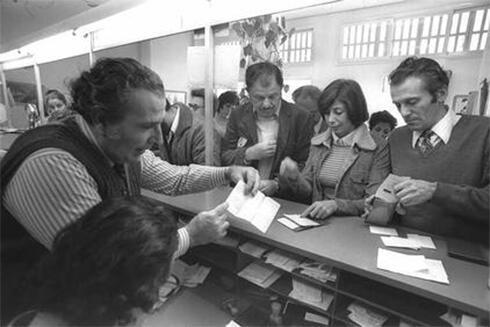

12 View gallery

“As fuel prices rise, electricity, transportation, and water costs have also gone up"

(Photo: Archive, Yedioth Ahronoth)

On Jan. 15, 1974, the public was also warned of possible ramifications: “The sharp increase in fuel prices will require difficult adjustments across all economic sectors. Individuals and factories alike will have to change their consumption habits and budgeting."

On March 22, 1974, a special report in Yedioth Ahronoth supplement titled “How to live with the energy crisis” described the fallout: “The first victim of the fuel price surge was the private car, and with it, an entire lifestyle.

Individuals living in the suburbs were expected to return to the cities, and the use of private vehicles was to be replaced by public transport. Housing will become dense and more functional. Clothing grayer and longer-lasting, and food more modest.”

The price surge continued. On April 9, 1974, the headline read: “Airline ticket prices to rise by another 8%, bringing the total increase over the past eight months to 21% - an unprecedented jump in civilian aviation history.”

On Nov. 15, 1974, a headline reported: “Transportation costs rise by 22%. Truckers had demanded a 37% increase."

On Feb. 3, 1974, it was reported that Israel Electric Corporation was considering building a coal-powered plant. By Jan. 15, 1975, the company announced that four power stations would be converted to coal. Within six years, a significant share of Israel’s electricity would come from coal-powered plants.

Now, 48 years later, Israel is preparing, almost impatiently, for a full transition away from coal-fired electricity, expected by the end of 2025.

Though Israel weathered the 1973 global energy crisis better than many countries, maintaining a relatively steady fuel supply, the government imposed an unusual restriction, inspired by the severe austerity measures seen across the West.

In cities like London and Paris, blackouts were imposed, cars were taken off the roads, and factories were shut down. Perhaps out of solidarity with Western allies who had supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War despite the Arab oil embargo, Israel introduced its own symbolic conservation effort.

Starting Dec. 16, 1973, Israeli car owners were required to stop driving one day a week, on a day of their choosing, to reduce fuel consumption. While prompted by rising fuel prices, the policy was also a political gesture.

The public, however, reacted with anger, and the measure was scrapped just two and a half months later.

The introduction of the “car Sabbath” also sparked tensions between religious and secular Israelis over the issue of abstaining from driving on Saturdays.

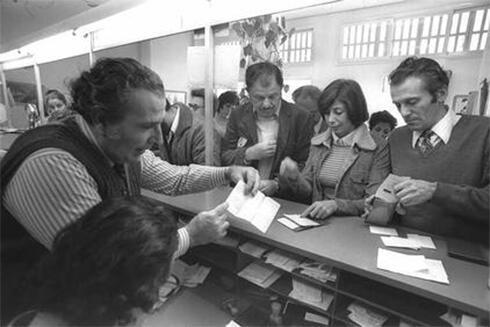

Drivers flocked to post offices to receive special stickers indicating their chosen “car Sabbath day”, Monday, Thursday, or another weekday. Vehicles were required to display these labels. Some drivers ignored the law, continuing to drive on their assigned days off. Others avoided registering their vehicle's sticker day altogether. Police began catching violators.

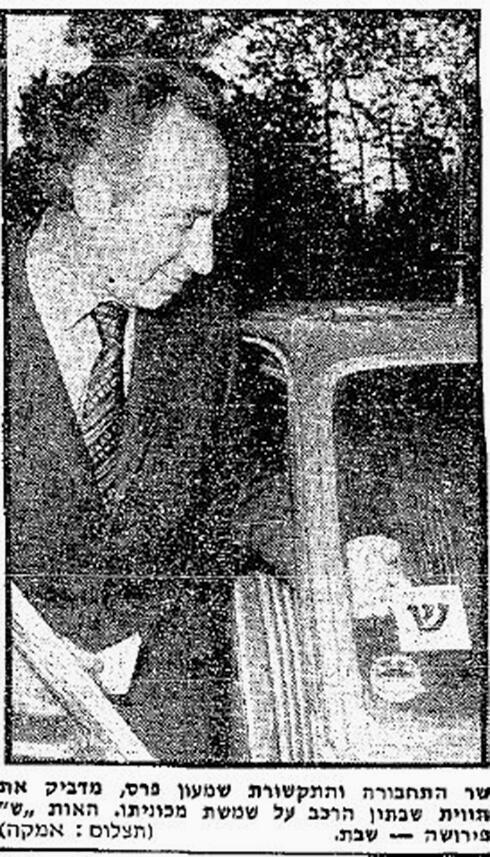

12 View gallery

Drivers flocked to post offices to receive special stickers for their chosen “car Sabbath day” השבתון

(Photo: Yaacov Saar, GPO)

On Nov. 27, newspapers reported that sticker distribution would begin Dec. 9, with the car Sabbath to take effect a week later on Dec. 16.

By Nov. 29, authorities clarified that drivers who chose Friday would begin their car rest day at 2 a.m., rather than at sundown Friday evening, as initially stated by Israel’s Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren.

On Dec. 9, reports noted concerns that the car Sabbath might disrupt public transportation. The newspaper also reported that it might complicate matters for soldiers. One reservist serving in Sinai, where no post office was available, was told to collect his sticker at the licensing bureau during his next leave.

On Dec. 10, the newspapers showed a photo of then-Transport and Communications Minister Shimon Peres affixing a sticker with the letter “ש” (Shin), denoting Saturday as his car's rest day.

When the restriction came into effect on Dec. 16, 1973, police gave only warnings. The full penalty of 3,000 Liras (then Israeli currency), a three-month license suspension, or both, was delayed. Soldiers on short leave were exempt from the restriction. By Dec. 20, the first violators appeared in court, where they were fined only 200 or 250 Liras.

That same day, it was reported that while fuel stations had full tanks, demand had dropped 25% since the war began. Additional price hikes were anticipated due to a surge in oil prices.

The next day, on Dec. 17, a spike in bus ridership overwhelmed the two public transport cooperatives, which had not prepared for the influx of travelers.

On Dec. 18, Minister Gad Yaacobi proposed offering additional incentives to encourage public transit over private car use.

Speaking on Dec. 23, Transport Minister Peres ruled out expanding the program: “There will be no second car Sabbath,” he said, dispelling rumors of a possible second day of enforced idleness.

He noted that the increase in public transit use was minor - just 2% - compared with the state’s fuel savings. Peres also noted that roughly 70,000 of Israel’s 200,000 private car owners had chosen Saturday as their day off.

On Dec. 24, in response to the growing strain on urban transit, IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar agreed to release 160 army bus drivers to help ease the burden of urban transportation.

On Jan. 1, 1974, another issue surfaced: a reservist had purchased a car with a “rest day” that didn’t match his schedule. Regulations prohibited switching days to prevent sticker fraud.

By Jan. 11, it was clear many drivers preferred to drive on Fridays, the most congested day of the week, despite the traffic. Few drivers had opted for a Saturday rest day, even though the government offered incentives for doing so. Officials hoped that new car sales would help balance out the weekday distribution.

On Feb. 3, the newspaper headline read that colored permits would be issued to soldiers driving their cars on Sabbath day. Rumors were also swirling that the entire policy might be revoked due to rising gasoline prices and the relaxation of similar restrictions in certain parts of Europe.

Before the policy was officially cancelled, a significant relaxation was introduced. On March 1, it was reported that the car Sabbath was shortened to 12 hours - from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. - down from the full 24-hour period, which had begun at 2 a.m. each day.

Then, on March 6, came the first sign: “Move to cancel car Sabbath beginning Saturday.” Public resistance had proven too strong, and the measure, largely ineffective and widely unpopular, was nearing its end.

On March 8, 1974, the announcement many Israeli drivers had been waiting for finally arrived. As Yedioth Ahronoth put it: “Hundreds of thousands of private car owners can breathe a sigh of relief. After just 72 days, Israel’s controversial 'car Sabbath' was officially canceled.

The emergency regulations authorizing the weekly driving ban expired and were not renewed, largely due to opposition in the Knesset presidency to even bring the issue to a vote in the full plenum."

Even after its cancellation, proposals to reinstate the ban resurfaced whenever global oil supply concerns reemerged.

On Dec. 30, 1974, four new proposals were submitted to the government, including one calling for a mandatory Saturday car ban and another to close central city streets to private vehicles.

Public criticism prevailed. The Ministerial Committee for Fuel Conservation, convened under Chairman Moshe Kol and reversed its earlier decision to enforce a car-free Saturday every other week.

Economic journalist in Jerusalem, Zvi Kessler, reported on one of the proposals involved in imposing a weekly Saturday driving ban to save an estimated $6–8 million annually.

The plan was later dismissed due to the lack of public transportation on Saturdays, which would have affected many citizens.

The idea of banning private vehicles one day a week was quickly shelved.

On Jan. 1, 1975, the Knesset’s Economic Affairs Committee rejected a proposal by Independent Liberal MK Hillel Seidel. Seidel argued that a car ban would reflect the global push to save fuel and show solidarity in the fight against what he termed “Arab oil extortion.”

The Transportation Ministry’s director general, Dan Hiram, countered that any fuel savings from a weekly ban would be minimal and could instead be achieved by raising fuel prices. The matter was dropped.

On Jan. 15, 1975, a new plan was announced in Tel Aviv: traffic and parking restrictions would be implemented to reduce congestion without requiring a full car Sabbath. During morning rush hour, private vehicles would be barred from key commercial streets, such as Allenby, Aliya, and King George, reducing traffic into the city by 3,500 cars daily.

On May 30, 1975, the government floated other energy-saving proposals, some practical, others far-fetched.

Ideas included closing gas stations on Saturdays and holidays, raising prices of large vehicles, enforcing speed limits, a car sabbatical day, different work hours, permitting installation of diesel engines in smaller commercial vehicles, and increasing purchase and import taxes on cars with high engine capacities by 30-40 percent.

None of these proposals were adopted at the time, and many remain on the shelf to this day.

This wasn't Israel’s first attempt to limit fuel use through vehicle restrictions. Back in 1950, the Transportation Ministry introduced a scheme to restrict private car travel; it was not in response to political pressure from an oil embargo, but due to a shortage of refined fuel. British-owned refineries were operating at just 15% capacity.

To restrict car travel, Israel was divided into dozens of zones, each designated by a letter. Car owners received windshield stickers indicating the zone in which they were permitted to drive. For example, “A” allowed travel within Tel Aviv only, while “C” permitted up to 25 kilometers in the greater Tel Aviv area.

This attempt was a failure. Thousands of drivers appealed, many obtained multiple stickers, and enforcement broke down. Of the 8,500 private vehicles on Israeli roads by late 1950, only about 5,000 were ever subject to driving limits. The program cut fuel use by a mere 5% and was quickly abandoned.

As for the 1973–74 car Sabbath, its actual impact on traffic was minimal. Many drivers ignored the law. Public transportation saw a slight uptick in use. However, increases in bus frequency were limited because many bus drivers were still on reserve duty following the Yom Kippur War.

According to data from that time, 10% of Israel’s 250,000 private car owners chose Sunday as their rest day; 20% chose Monday; 16% chose Tuesday; 9% chose Wednesday; 10% chose Thursday; just 4% selected Friday, making it the most popular driving day.

Saturday proved to be the most effective day off, with 31% of drivers, mostly religiously observant, opting to abstain from driving.

On March 8, 1974, the car Sabbath officially ended. Economic Minister Gad Yaacobi announced that Israel had reduced its fuel consumption by 10% during the program’s short life. Wear and tear on vehicles also declined, with less need for replacement parts and new tires.

Still, the oil embargo inflicted deep economic damage on Israel and many other nations.

As oil prices rose by hundreds of percent, the cost of imported raw materials soared. Combined with ongoing transportation challenges, Israel entered a cycle of inflation. Prices rose 20% in 1973, jumped to 40% in 1976, and by the early to mid-1980s, inflation spiraled to 500%, a peak reached in 1985.