Yaffa Golan woke up a little more than a year ago in her home in the moshav of Porat, in central Israel. That Sukkot holiday, she planned to travel with her husband to Jerusalem for the Kohanim Blessing ceremony. Because it was also her youngest daughter Shirel’s 22nd birthday, and it was important to her to be with her on that day, she suggested that Shirel join them.

Shirel, who at that point was barely getting out of bed, refused.

“Shirel was emotionally extinguished, fed up with life,” Yaffa recalls. “The last two weeks were the worst. She did not even come out for Friday night kiddush. She did not eat anything.”

Shirel's parents left the house at around 8 am. “At 10:30 I texted her, she did not answer,” Yaffa says. “I called again at 11:00 and she hung up on me. I suspected something was wrong. I asked Adi, her partner, to check.”

Adi Gilad, 27, had been Shirel’s partner for about three years. “We spoke Saturday night,” he says. “She wrote that she wanted me to come over. I answered late and she got upset. I told her we would meet tomorrow and do something for her birthday. She wrote to me, ‘Who knows what will be tomorrow.’ I answered, ‘What do you mean, what will be tomorrow?’ She said, ‘Who knows where I will be.’ I never imagined in my life what was about to happen.”

Adi arrived at the house in the moshav around noon and began searching for Shirel. “I went up to the treehouse in the yard,” he says. “She liked being there at that time. I saw her phone and a cup of coffee, meaning she had still been drinking coffee that morning.”

Adi continued searching until he eventually found her lifeless in another corner of the yard. “I did not understand at all what I was seeing. I could not get close. I screamed like I have never screamed in my life,” he says quietly.

He called for help, but it was already too late. A Magen David Adom team pronounced Shirel dead, likely about three hours earlier.

Shirel Golan was a survivor of the Nova music festival. Since the Black Saturday of October 7, she was unable to return to herself. She sank into depression, received treatment and was hospitalized, including about a week in a closed ward at Lev Hasharon Psychiatric Hospital. According to her family, no treatment provider truly managed to help her, and the week of hospitalization only worsened her condition.

At the end of June 2024, just months before her death, I met Shirel as part of an investigation for an article about Nova survivors. The meeting took place at a small café in the Florentin neighborhood of Tel Aviv, near the apartment of her older brother Lior, one of the people closest to her, with whom she was living at the time. Only a few days earlier, she had been released from the hospital.

The figure I met was captivating, full of energy, warm and smiling. Yet alongside that, it was clear that some of the energy was tied to severe psychological distress. Her eyes darted around, she spoke with everyone nearby, repeatedly interrupted the conversation for various reasons, became irritated by noises in the café and complained that beeping sounds from nearby tables were driving her crazy.

'Hospitalizing her in a closed ward was a mistake. She came voluntarily because she had lost control. After they placed her in a closed ward, she completely unraveled. I met with one of the doctors and told them, ‘Listen, she is a Nova survivor. You have to treat her differently. You are putting her in a closed ward with people in far worse condition, and it labels her as if she is insane.’

“I’m 21, I live in a moshav,” she told me. “My childhood was not simple. My mom worked late, my parents were always busy.” She was the youngest of five. “We’re five siblings, 39, 38, 36, 29 and I’m 21, so I grew up with older siblings. They taught me everything. I watched ‘Malbi Express’ and all those movies, like ‘Givat Halfon Doesn’t Answer,’ when I was four. My dad is totally ‘Givat Halfon Doesn’t Answer,’” she said, laughing.

She always loved parties. “I’ve been going out to techno since I was 16 with a fake ID,” she admitted with a smile.

Tell me about Nova.

“I arrived with Adi at 11 p.m., which is as early as it gets. The Nova stage had not even opened yet, that only happened at 3 a.m. I told Adi I wanted to dance, I wanted to go crazy because I was enjoying the music so much.”

At 6:29 a.m., the rockets began.

“Adi and I sat on the ground until around 7 a.m., watching the rockets explode. Around 8:10 we got into the car after loading all the gear. At 8:15 we were already driving. At 8:20 we reached Route 232, that road of death.”

Shirel stops and asks for a piece of paper to draw. She sketches the area of the party and the attack points. “Here people were murdered, and here people were murdered. They just closed in on us like this, and Adi and I are nearby, standing in insane traffic. Everything was one big traffic jam. The entire road was full of blood. Full of abandoned cars with no people.

“We said we’d turn right, it was blocked. My friend Moriah, may her memory be a blessing,” she says, referring to Moriah Or Suisa, “was in the car next to us. I suggested she come with me. She said she had her own car. Two minutes later, she was blown up. I want to erase Nova from my life. We hid for three and a half hours. The car stalled,” she adds, mixing past and present.

“We ran a kilometer to the end of the wadi,” she continues. “Eight pickup trucks of terrorists arrived. We were still hiding. In the end, a Bedouin police officer named Remo Salman El-Hozayel saved us. He found us and evacuated us.” She later maintained close contact with Sgt. Maj. El-Hozayel, who even came to sit shiva after her death.

The horrors of that morning were only the prelude to Shirel’s nightmare. In the three months that followed, she shut herself inside the house. Her partner Adi was called up for reserve duty. “I was alone and traumatized. Without treatment,” she said.

Her condition deteriorated steadily. When asked about that period, she said, “I was afraid to get treatment. I was afraid to say, ‘I need help.’”

In January 2024, she flew with Adi to India for three months, during which they broke up. After that she returned to Israel for a week and then flew again to Goa, this time without him. “She connected with other people. She thought India would be a refuge,” Yaffa says. “The second time she was already unstable. Everything surfaced. Without Adi, she had no anchor.”

6 View gallery

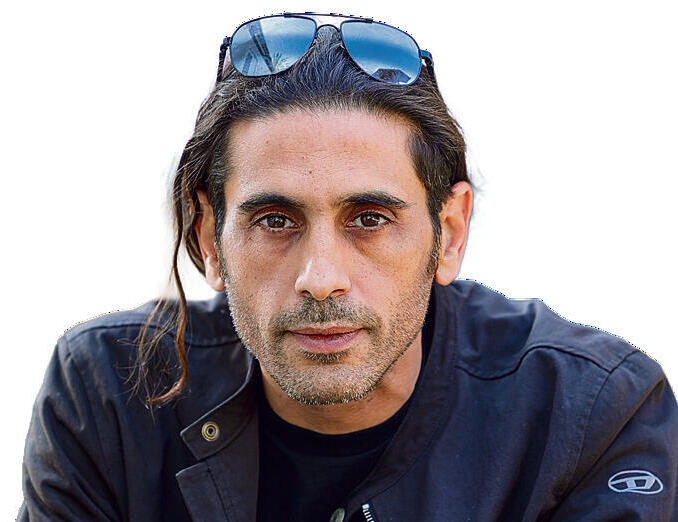

'She thought India would be a refuge,' Yaffa Golan, beside a photo of her late daughter, Shirel

(Photo: Shlomi Yosef)

Yaffa says the family received reports about Shirel from an Israeli woman living in India. She said Shirel fought with people, was involved in an accident and was being pressured to pay compensation. Her brother Lior paid 1,000 shekels.

“Then my husband decided to go bring her back. He flew on Tuesday, reached her on Wednesday, they spent 24 hours together. They went to a restaurant and took a motorcycle trip. At first she said, ‘Why did you come, I don’t want to return to Israel at all, I want to fly to the US’ 'He insisted,' Yaffa continues. 'She was confused, very unstable, did not know what to do with herself. She could not work, had just broken up with Adi and everything was mixed up for her.'

In June, Shirel went on her own initiative to Lev Hasharon Psychiatric Hospital. She was examined, a psychiatrist determined she was in a psychotic state and ordered her hospitalization. The next day she attempted to escape by pressing a fire alarm button. Following a trigger she experienced, she confronted staff members and, according to her family, was assaulted by four of them. In response, she was forcibly placed in an isolation room, resulting in bruises in various parts of her body.

Toward the end of our conversation in Tel Aviv, Shirel said: “The state abandoned me. In hospitalization they beat me, pinned my head to the floor and gave me an injection in front of everyone. I did not resist. I was lying there with my hands behind my back.”

We parted with a hug and agreed to stay in touch. I did not know she had sunk into deep depression. We never spoke again before her death.

Following her death, a committee was established to examine the circumstances of the suicide, headed by Prof. Gil Zalsman, chairman of the National Council for Suicide Prevention. The committee, formed at the request of Lev Hasharon director Shmuel Hirshman following the family’s claims that the hospital bore responsibility, examined her hospitalization.

The committee determined that while no direct link was found between the hospitalization and the suicide, the family’s complaints regarding violence Shirel experienced in the ward were found to be justified. It ruled that her transfer to isolation included throwing her to the floor, which appeared to the committee as “an unnecessary act of force when it was no longer required.”

Staff members claimed Shirel resisted strongly and they found no other way to carry out the procedure without being harmed themselves, but the committee assessed that a different professional approach was possible.

“I imagine her being thrown into isolation, screaming her soul out and no one answering her, and I collapse,” says her brother Lior. “The closed ward hospitalization was a mistake,” he adds. “She came voluntarily because she lost control. After they put her in a closed ward, she completely lost it. During the week she was there, I met with one of the doctors and said, listen, she’s a Nova survivor, you have to treat her differently. You put her in a closed ward with people in far worse condition, and it labels her as if she’s insane.”

'Being without Shirel is like being without life. Her absence is so great, it feels as if it happened today. The sense of what was lost, when I see the survivors now, is overwhelming. I tell myself that if she had just held on a little longer, she would have made it through. I look for her, for her touch, for her scent. I have a dress of hers that I like to smell. Her scent still clings to it'

Dr. Assaf Shalev, deputy director of the hospital, testified before the committee that the family complained about violent isolation and demanded her release. He examined Shirel and assessed that she was in a manic-psychotic state with danger to her surroundings. The family pressed to move her to an open ward, claiming she was being treated violently, and he refused. That same day the family filed an appeal to a regional psychiatric committee requesting her release, but the appeal was denied.

Shirel remained hospitalized for four more days.

“That week caused her a crisis of trust in medical institutions,” Lior claims. “She no longer agreed to treatment. She refused to go to ‘Kfar Izun.’ She stayed at home and sank into depression.”

Adi, who reunited with Shirel after her release, says, “They shut her down. She came to them in a high and they shut her down and sent her home. Before Nova she was happy, social, full of ambition.”

“These are young people who came to the best place and were waiting for sunrise, the peak of the party, and someone brutally shattered their world,” explains Karen Golan, a social worker and psychotherapist at the Izun Association.

She describes the difficulty survivors have in accepting treatment. “We saw young people who thought that if they smoked, went back to parties, distanced themselves, they would return to themselves. In reality, the opposite happens,” she says. “Often they take unknown substances and then experience severe panic attacks. They would call me in the middle of the night confused.”

The Izun Association specializes in treating young people with trauma. In an effort to help Nova survivors, it has held 12 retreats for survivors in India. Shirel herself participated in similar retreats run by other organizations.

What she experienced there is unknown, but a glimpse into an Izun retreat, which lasts four and a half days, gives a general sense. “The survivors were so scattered that even a daily schedule like yoga and meals gave them a sense of security,” Golan says. “We worked from morning until night, breathing, meditation, mindfulness. We touched lightly on memories seeking relief. We did not call them traumas.”

She adds that some extreme cases required extended stays.

“There was a woman who was supposed to arrive at Nova but did not, yet was at a nearby kibbutz,” Golan says. “Her friends were murdered at the party. She came to India, took mind-altering substances and called me in the middle of the night from Dharamsala. She said she was confused and terrified. I told her, ‘Take a taxi and come.’ I met a broken woman with cuts on her arms. She stayed for two weeks and then continued traveling.” Golan did not treat Shirel, but refers to similar edge cases.

“There is helplessness. There are party survivors who have not touched what they went through at all. They suffer greatly and experience suicidal attempts. Some are only now ready to begin treatment. And it’s not that they immediately open their hearts. It takes maturity to dare touch the wounds.”

She explains that the process is gradual. “I know there is trauma but we do not touch it yet. It takes patience. If I touch it now, I flood them. We do a lot of work on resources and only afterward work on events. We choose an event, not the hardest one, and we invite the memory.”

She adds that many survivors carry overwhelming guilt. “Some have not told me the hardest event even after a year and a half. The point is that through the work they learn that I am not overwhelmed by the memory every moment. I can hold it.”

“I still imagine her walking through the door asking, ‘Mom, what’s there to eat?’” Yaffa Golan says during a meeting at her home. Photos of Shirel are everywhere in the living room, her drawings hang on the walls, and her mother displays jewelry she created for sale.

After her hospitalization, Shirel decline was severe. She sank into deep depression and barely left the house. At night she asked to sleep with her mother. “I stopped working so I could help her,” Yaffa recalls.

A month before her death, Shirel attempted suicide for the first time.

“I came home and saw she was swollen,” Yaffa says. “She said, ‘I took pills because I wanted to feel good.’ She did not want to go to the hospital, but I insisted.”

Only at the hospital did Yaffa learn the painful truth. Shirel hid the truth even from her partner. “I asked how many pills she took,” Adi recalls. “She said just a few.”

Her family is angry. During that period, Shirel was still undergoing follow-up examinations by senior doctors at Lev Hasharon, who did not signal her distress.

“The point is that when she was not supposed to be hospitalized, they hospitalized her in a closed ward. And after her suicide attempt, when she should at least have been under supervision, no one saw her,” Lior says.

Adi adds, “After the hospitalization she fell into severe depression. I would come over, we would just sit and watch TV. I would say, ‘Let’s go out, grab a drink.’ She would say she didn’t feel like seeing people.”

The family also blames the local authority.

“The social worker from the regional council who accompanied her for a time was not available before her death,” Yaffa claims. “Twenty days before Shirel died, I spoke to the social worker and she said, ‘I can’t do anything until she comes to my office.’ Shirel was not getting out of bed. I asked her, ‘And if she kills herself?’ She answered, ‘I don’t know what to say.’”

Omri Frish, president and founder of Kfar Izun, says that around May, “a lovely young woman arrived, with good energy, like a ray of sunshine, full of smiles. She said she wanted to join the program. For two weeks she came but did not persist. That was about six months before her death.” After her suicide attempt, they tried in many ways to convince her to return, even partially. “A week before the incident, I personally spoke with her on the phone,” Frish says. “She loved coming to me, getting a hug, talking. I said, ‘Just come chat with me a bit.’ She did not want to.”

“There are people who are hard to save,” Golan says. “They don’t come to treatment. They travel the world, use drugs and alcohol, telling themselves they are treating themselves, when in fact they are stuck.”

In a recent Knesset committee discussion, National Insurance Institute data revealed that of 3,559 recognized Nova survivors, only half returned to work for at least five consecutive months. Ten percent worked three to four months. The rest have not returned to work and are dealing with severe trauma. Committee chairwoman Naama Lazimi said that two years after the first discussion, government responses are still lagging.

Another tragic case recognized by the Health Ministry as suicide following the massacre is that of Roi Shalev, 30, who witnessed his partner being murdered. He himself was under terrorist attack for long hours and was seriously wounded in the back. At the party, he also lost his close friend Hili Solomon. Two weeks after the attack, his mother, Rafaela, died by suicide.

In the months that followed, Roi began speaking publicly across Israel and around the world. “It was extremely important to him that the whole world know what happened here,” his father, Ronen Shalev, says. “The problem was that he did not take care of himself.”

Eight months before his death, his strength ran out, and suddenly Roi decided to stop lecturing. “He was simply exhausted,” Ronen says. “He settled at home and seemingly returned to routine, but inside he was dead.” During that period, Ronen decided to move with his son to a quiet moshav in central Israel. Ronen says he saw sadness in his son’s eyes but did not understand how deep the crisis was.

“He was murdered on the 7th, and he died two years later,” he says.

On October 10 of this year, Roi wrote on social media that he could no longer cope with the grief and asked forgiveness from his family. Hours later, he was found lifeless in his car near his home.

“You have to push survivors to go to professionals and explain that it is not enough just to seek help. You also have to want the help,” his father says. “The big problem is that the soul is transparent, even in the eyes of the state. Every medical committee of the National Insurance Institute crushes them. They collapse because they are forced to think and tell the story all over again.

“They bring proof of how hard it is for them, and if the psychiatrist hears that they traveled abroad or returned to work, they assume they are rehabilitated. But that does not mean a person is rehabilitated. They are only trying to recover. They are not there yet. A situation has been created in which survivors fear these committees and think only about how to present themselves as more broken. They need to go to work knowing the state supports them. Only then will they be able to return to a normal life.”

“Today, two years later, it can be said that the events of October 7 are unlike anything we have known in terms of mental health,” adds Omri Frish. “Just as legislation was enacted for Holocaust survivors, a law must first be passed that allows for an appropriate response. In addition, paths must be found that do not force survivors to declare themselves mentally disabled.

“Today, almost every lawyer advises them not to go to work and not to tell committees about travel or studies. That is not good. They should be encouraged to reintegrate into society without this harming the assistance they receive from the state.” Frish also emphasizes that government ministries must provide a special response for extreme cases.

“They do excellent work, especially the Welfare Ministry and the National Insurance Institute, but of course there is room for improvement,” he says. “More than a year ago, we proposed that the government adopt a model once used by the Defense Ministry, to establish dedicated teams for survivors who are at the edge. The moment a report of a suicidal case is received, people would immediately go to that person.”

Two months ago, the family of Shirel Golan marked one year since her death.

“Being without Shirel is being without life,” Yaffa says through tears. “Her absence feels as big as if it happened today. That sense of what was missed, when I see the survivors now, is overwhelming. I tell myself that if she had just held on a little longer, she would have gotten through it.

“I look for her, for her touch, for her scent. I have one of her dresses that I like to smell. Her scent still clings to it.”

Yaffa sits in her living room and looks toward the small window from which the caravan where Shirel lived can be seen. “We sit here, see the outline of the caravan and think that any moment she will come, walk in and open the pots. Every Friday I used to prepare several dishes. Today I no longer cook. Life has lost its flavor.”

“I was so happy she survived Nova,” says her brother Lior. “And it was so shattering that she died by suicide. It does not register. I thought she was shutting herself at home because she had gone through a hard year and had a lot to catch up on. I had no idea.”

Her former partner understands her words only in retrospect.

“When I remember that sentence, ‘Who knows what will be tomorrow,’ I realize she was probably thinking about it already,” he says. “It was not a spontaneous act.”

“People reach a breaking point where death seems preferable to life,” Frish says. “We will not manage to save everyone. But we are obligated to try.”

Responses

In response to the claims against Lev Hasharon Medical Center, the Health Ministry said: “The Health Ministry provides therapeutic care to every patient in need, taking into account their medical, emotional and mental condition, in accordance with the law. The Health Ministry expresses its deep condolences to the family. Due to medical confidentiality, we cannot address the details of the case.

“The review committee established by the Health Ministry was composed of professionals external to the ministry and carried out its work thoroughly and over an extended period. The Health Ministry instructed that the deficiencies identified by the committee be corrected. We note that some of the claims are in significant discrepancy with the facts found by the committee.”

The Lev Hasharon Regional Council said in response: “The council and its head express their deep sorrow over the tragic case and the loss of Shiral Golan, of blessed memory. Our hearts are with the family in this difficult time, and we share in their profound grief.

“The council, through its welfare department and professional staff, acted throughout to the best of its ability to provide Shiral, of blessed memory, with the best possible support and services. Out of respect for Shiral and her family, and in order to preserve privacy, we will not detail the actions taken. We remain in close, continuous and supportive contact with the family and accompany them with sensitivity and respect. The council is committed to continuing to act responsibly, sensitively and professionally for the community of Lev Hasharon, especially in complex distress situations.”

If someone around you is in crisis and may be suicidal, do not hesitate. Speak with them, encourage them to seek professional help and stress the importance of doing so. Try to assist them in reaching community professionals or national support services, including ERAN’s hotline at 1201 or via WhatsApp at 052-845-1201, the Sahar website, or headspace.org.il.