On a quiet stretch of Mediterranean coastline in the Western Galilee, just north of Nahariya, a cluster of stone buildings faces the sea under a flag that suggests something slightly out of the ordinary. It is not the flag itself that draws attention so much as the insistence behind it.

This is Akhzivland — a self-declared micronation founded in 1971 by Eli Avivi, which over time became less a political statement and more a long-running coastal curiosity. Neither fully a state nor merely a private home, Akhzivland settled into a space of its own: part museum, part guesthouse, part personal universe shaped by one man’s ideas of freedom, eccentricity and endurance.

The site sits beside the ruins of ancient Achziv, an important port city dating back more than 3,000 years. Archaeological traces from the Iron Age, Roman period and later eras are scattered throughout the area, which today includes a national park, coastal and marine nature reserves and the remains of the Arab village of al-Zeeb, whose residents fled during Operation Ben-Ami in 1948.

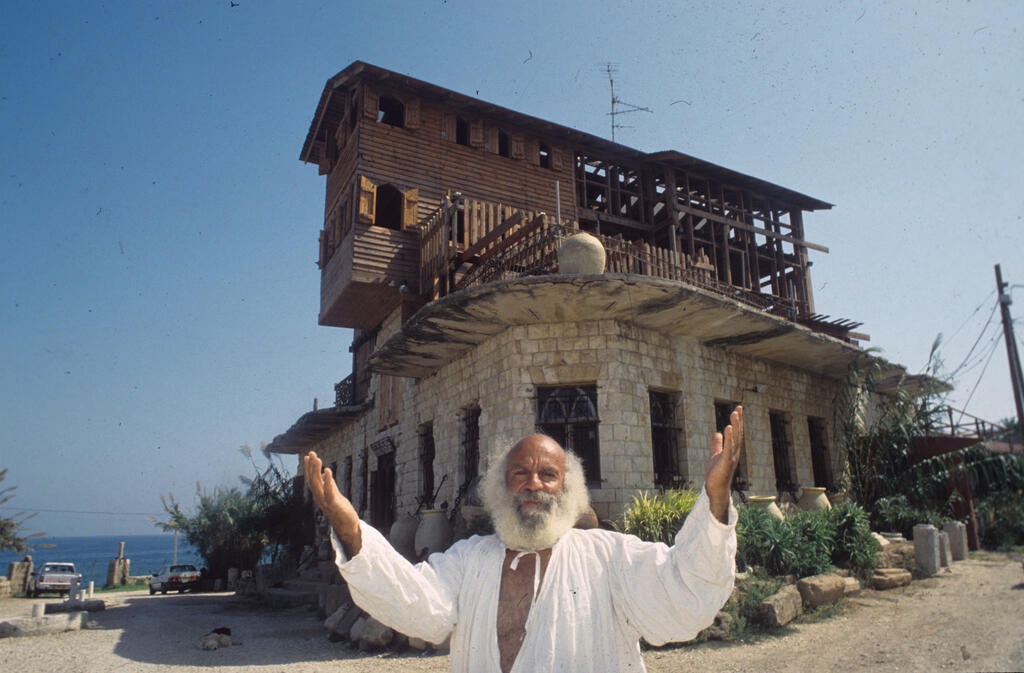

Avivi arrived here in the early 1950s. Born in Iran and a Palmach veteran, he leased two neglected stone structures along the shoreline and rebuilt them using unconventional methods — stone at the base, wood above, finishing touches guided more by instinct than regulation. Inside, he assembled an eclectic museum of local finds, from anchors and pottery to everyday objects recovered from the sea, displayed openly and without glass.

The place gradually attracted visitors. By the late 1960s, young people, artists and travelers were coming not for ideology but for atmosphere — informal, permissive and largely disconnected from the routines of daily life elsewhere. As interest grew, development plans followed. Authorities approved a national park and a nearby resort, and in 1970 Avivi was informed that his home would be demolished.

The response was characteristically unorthodox.

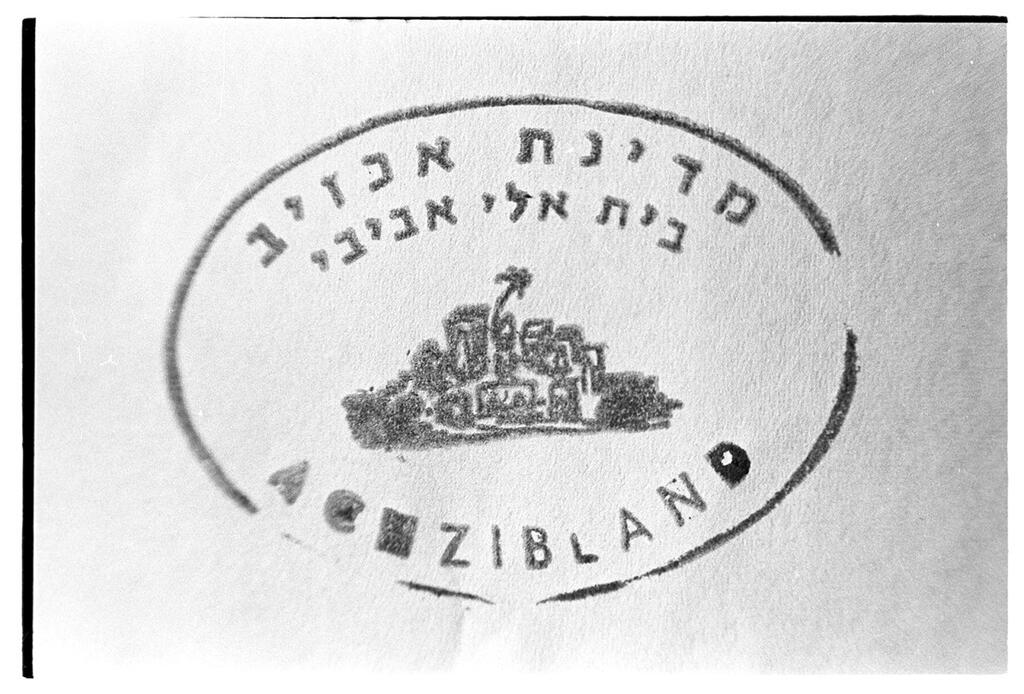

In 1971, Avivi and his wife, Rina, announced the founding of the “State of Akhziv.” The declaration came with a flag, an anthem, symbolic passports and a constitution that named Avivi president, elected by his own vote. Visitors could request a special stamp in their passports — a novelty that became part of the site’s identity and occasionally caused confusion far beyond the beach.

Authorities arrested Avivi and charged him with creating a country without permission. A judge later ruled that no such offense existed in law. Avivi was fined a token amount for destroying his passport and released. After further legal proceedings, the land was leased to him for 99 years, without recognition of sovereignty and without further attempts to remove him.

Over time, Akhzivland became known less for its legal oddities and more for its lifestyle. It functioned as a loosely regulated enclave, attracting travelers, artists and couples seeking civil marriage ceremonies unavailable through official religious institutions. Public figures visited over the years, sometimes out of curiosity, sometimes simply because the place existed at all.

Avivi himself became part of the attraction. He cultivated a public persona that mixed provocation, storytelling and deliberate ambiguity. Among the more persistent elements of that mythology was his claim to have amassed a vast private archive of nude photography over decades, much of it taken at Akhzivland during its freer years. In interviews, Avivi spoke openly of the collection, which he said numbered in the hundreds of thousands of images.

The photographs were never formally exhibited and were known mostly through Avivi’s own accounts, which blurred the line between fact and exaggeration. Like much else about Akhzivland, the archive existed more as legend than institution — an extension of Avivi’s tendency to turn his personal life into part of the site’s ongoing narrative. What became of the photographs after his death remains unclear.

In 1971, the enclave briefly intersected with regional violence. Six members of Fatah arrived by boat from Lebanon, intending to kidnap Avivi. One entered the house carrying explosives and was confronted by Rina Avivi at gunpoint. He dropped his weapon and fled. Security forces later detained all six infiltrators. The episode passed quickly, and Akhzivland carried on.

Electricity arrived in 1988. The museum expanded. The self-declared state gradually shifted from countercultural experiment to recognized oddity, eventually even promoted as a tourist attraction. Today, it includes a guesthouse, beachfront campground and a museum displaying archaeological finds without barriers, at eye level, accompanied by handwritten explanations.

Avivi lived at Akhzivland until his death in May 2018 at age 88. Since then, the population has remained stable at exactly one permanent resident: Rina Avivi, its only remaining “citizen.”

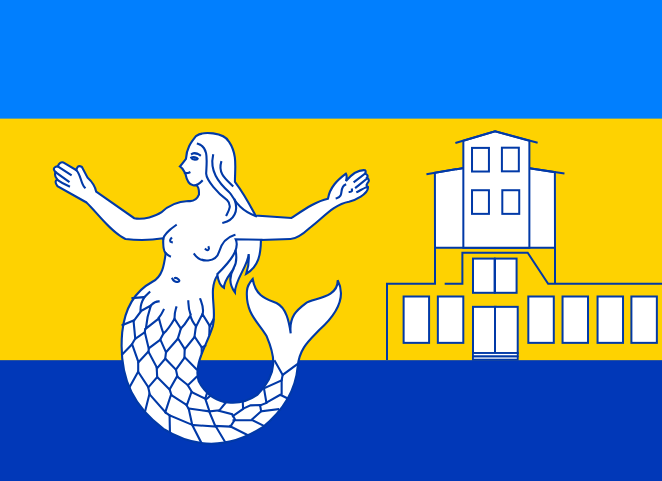

The flag still flies — two blue stripes with a wider yellow band between them, bearing a stylized image of the museum and a mermaid borrowed from a Dutch municipal emblem. The passports are souvenirs now. The presidency is vacant.

Akhzivland never changed borders or laws. What it did instead was linger — a place where history, personality and performance quietly fused, leaving behind a coastal anomaly that continues to invite visitors to decide for themselves where the story ends and the legend begins.