In order to interview Krystsina Tsimanouskaya, the Belarusian runner who sought political asylum in Poland during the Tokyo Olympic Games, we had to send a written request behalf of Ynet's sister publication Yedioth Ahronoth, photos of our passports and a recommendation from the Polish foreign ministry.

When the approval arrived, we were told to drive to the Mokotów section of Warsaw and there, on a multilane highway, between a derelict supermarket and a store offering goods ranging from a hot tub to nails, we found a newly built four storey office building - which was our final destination.

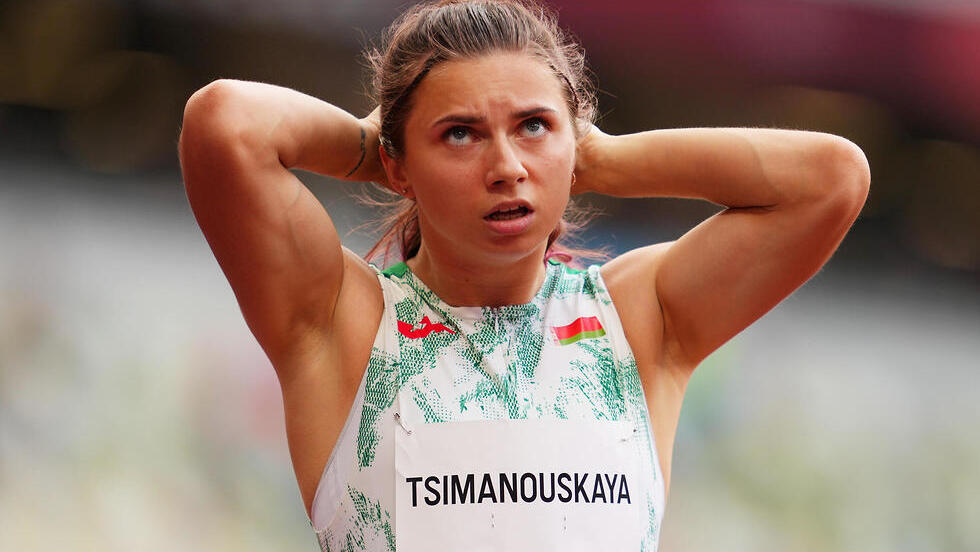

9 View gallery

Krystsina Tsimanouskaya after her arrival in Poland having received a humanitarian visa following her defection from Belarus

(Photo: EPA)

A publicist from the Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation, an organization assisting defectors, punched a code on the security door and led us to a modest third floor office space that had several small rooms and a few potted plants.

This was the Belarus shadow government's base of operations.

Pavel Latushko, a former minister and diplomat in the government of Belarus leader Alexander Lukashenko, occupied an office at the end of the hall.

He is designated to head his native country's government, should Lukashenko be ousted and is also at the top of the Belarus KGB's hit list and had already survived poisoning in an attempt on his life that was attributed to the regime, which has accused him of terrorism.

But the six large Polish security men, in civilian clothes over their bulletproof jackets, with their weapons bulging and earpieces protruding, were not on site to protect the former minister.

They were there to protect the defecting runner after her government attempted to abduct her and deliver her back home.

When we entered, I was told to strip down to my outerwear, my bag was emptied, and its contents searched. Meanwhile, a security guard slowly ran his metal detector along my body.

Tsimanouskaya's husband who is also her personal coach, emerged from one of the rooms. He escaped from Minsk on the night of his wife's defection, having had advanced warning of her intentions. Their wedding date is tattooed on his arm. They've been together for eight years and married for three.

I entered the small room adorned by flags of Poland and the EU with its shutters closed and sat across from Tsimanouskaya. She wore black sneakers, black pants and a white sweater. Even though she is 24 years old, she appeared and even sounded like a child. What she had to say, however, was no childish matter.

Her famously red hair had been dyed blond and a newly purchased pair of glasses rested on her nose. This was her only indulgence in the weeks since her dramatic escape.

While one of the security men remained with us, the publicist came in carrying six bottles of water. The guard poured some into a cup, tasted it and waited two minutes before offering the bottle to Tsimanouskaya.

Let's go back to the moment your world changed, tell me what you felt as events evolved.

"I returned to the Olympic village after the 100-meter race and found a message that I was scheduled to participate in the 4X400 competition – which I had never run, and another race that was more suitable for taller runners with longer muscles than mine. I get tired after 200 meters," she says.

"I remembered Lukashenko's warning to us before the Olympics, that if we do not come back with medals, we need not come back at all and realized that if I participate in that race, I will be destroying my chances for a medal in the 200m race, which was my primary purpose for coming to Tokyo," Tsimanouskaya says.

"This was a failing of the Belarus officials who neglected to send in drug testing results for the runners who were originally set to participate in the race," she says.

"I sent a text to team officials, but they did not respond. I was angered by the lack of respect that is often shown towards Belarus athletes. We train hard, beyond our physical and mental capacities, often deprived of enough proteins in our diet, but are still required to show loyalty. I posted the whole story on my Instagram and said I am being forced to run although I was not consulted, naming the officials responsible and claiming that they were using me to hide their own mistakes," she says.

"This was an emotional outburst on my part and was posted without any consideration of what might follow. Soon after, the head coach of our delegation and an official from the Belarus Olympic Committee came into my room and demanded that I remove the post, which I did."

Tsimanouskaya recorded her exchange with the officials, which was later posted online.

In the recording the coach and another official ask her to remove her Instagram story. She tells them that all she wants is to run her race. The two men threaten her: "This is how you can end up in what will appear as a suicide," they tell her.

Belarus television later interviewed her but broadcasted an edited version of the interview in which she appears to say that she had suffered from temporary insanity when she posted the story.

"It's crazy that they ran my Instagram story over and over but crazy is normal in Belarus," she says.

"I thought that was the end of that but the next day, I was visited by another official and a psychologist who works in a mental institution in Minsk. I was told that I have half an hour to pack my gear and then I will be committed to a psychiatric hospital with rapists, murderers and people who had tried to kill themselves. He tried to cause me to scream at him and cry, but I held it together. I was not prepared to give him that pleasure.

"At that point I understood that when you speak out against the government you are branded insane. Then I realized that I no longer had a country. I felt shocked and was in panic," she says.

"I was also hungry having not eaten for the past 10 hours. I slowly began gathering my stuff. It took about 90 minutes and meanwhile I began making calls."

You've just thrown the past five years of your life away and are being kicked out of the Olympic village with no home to go to. How did you keep from breaking down?

"At first I did not really understand the situation. Then I remembered that in the movies, when the protagonist is injured, he is always told not to lose consciousness. Stay with us' they always say, so I told myself to stay with myself.

"I called my husband and hinted that he must get himself ready to flee the country. Then I called my grandmother and the BSSF that helps exiled athletes from Belarus and they told me the decision to stay or leave was mine alone, but they thought that a return to my country would mean jail or a mental hospital and that if I chose to defect, they would help me," she says.

"I walked towards a car with the psychologist walking behind me. I sat behind the driver and the official sat by my side. My mind was racing. I called my husband again and let him understand it was time for him to move.

Then I called by grandmother again. Like all pensioners she is a supporter of the government. We've had many arguments over that in the past, but this time she said: 'You know I love you my child, but don't you dare come back to Belarus. They've been claiming you are insane for hours.' I became terribly sad but there was no longer any question in my mind. The only thing was to figure out how I was going to escape," she says.

"The drive to the airport took about 40 minutes and at first I considered tearing up my passport but understood that would not help. Then I took out my phone and looked up on Google Translate how to say: 'Help me I am being taken against my will,' in Japanese."

How did you keep so calm?

"I played scenes in my mind from the millions of Hollywood action films I had seen and thought what the hero would do."

What gave you the idea to use Google Translate?

"Brad Pitt in Ocean's Eleven."

There is no such scene in the movie

"Yes, but I learned how to fool the system, from him."

What kind of a dictatorship allows you to keep your phone?

"I think no one expected me to have the courage to take a stand against the regime," she says.

"When we entered the terminal, the officials walked ahead of me towards the gate for the flight to Istanbul. There was a Japanese police officer at a different gate, and I showed him my phone. He had a hard time communicating with me and ran off. I was scared that my minders would turn around a see where I was. My phone battery was also about to run out. But the officer came back with another policeman and they took my passport and luggage and protected me while they called the International Olympic Committee."

9 View gallery

Krystsina Tsimanouskaya after approaching a police officer to ask for political asylum at the Tokyo airport

(Photo: Reuters)

Tsimanouskaya was taken to a hotel in the city under heavy guard. She appealed to the Olympic Committee to be allowed to run the 200m race but was refused.

On the next morning she was taken to the Polish embassy and informed that she would be given a humanitarian visa to Poland. Her husband, who had managed to leave Belarus by car - first crossing into Russia and then to Ukraine - was also granted the same visa.

After boarding a flight to Warsaw, and despite believing that she had survived her ordeal, Tsimanouskaya was suddenly removed from the plane by two Polish diplomats and placed on a flight destined for Vienna.

When the plane was flying over the Russian airspace, the diplomats frantically went over maps and communicated with the cabin crew and pilots. They were genuinely afraid the plane would be forced to land after a Ryanair flight carrying a Belarusian dissident - Roman Protasevich - was forced out of the sky by the Belarus Airforce earlier this year, prompting world condemnation and sanctions against the Lukashenko regime.

"Once we made it past the Russian airspace there was a sigh of relief," Tsimanouskaya says.

9 View gallery

The airline carrying Belarus opposition activist Roman Protasevich after being forced to land in Minsk last May

(Photo: EPA)

Who was behind the attempt to capture you?

Tsimanouskaya hesitated to answer that question for a while. Though her English is excellent, she is careful when speaking of the Belarus dictator and opts to use the services of the translator. Her mother had already received threats at the bank where she works.

"Only one man calls the shots in Minsk," she says.

Freedom always comes at a cost. Especially when it is achieved through worldwide humiliation of a ruthless dictator by a 24-year-old woman.

On the day she was granted her visa to Poland, a Belarusian living in Ukraine who was providing aid to others trying to flee, was found hung in a park near his Kiev home in what was made to appear as a suicide.

Tsimanouskaya is heavily guarded, at all times. Her food and drink are tasted by security men, and before she enters any location, it is inspected carefully.

She cannot speak to any other Belarusians directly and can only communicate via internet. Although she receives many messages of support, she has also been sent graphic messages, threatening her life. "I cannot even shop online because I don't know the address of my apartment," she says. "The street sign has been removed."

She has few clothes. Only what she packed for the Olympics and a few pieces given to her after she arrived in Warsaw. She lives in a modest apartment and has the services of a cook who prepares meals that are appropriate for athletes in training - at the cost of the Polish taxpayers.

She had already competed in a previously booked local event but finished her race with a poor result. "My feet were empty," she says.

Dozens of security men guarded the stadium and as the crowd cheered her, she covered herself with the Polish red and white flag, the same colors that the opposition in Belarus uses.

9 View gallery

Krystsina Tsimanouskaya wrapped in a Polish flag after her first competition since her defection from Belarus

(Photo: EPA)

"If you wear clothes in those colors you can get arrested in my home country," she says.

Poland is home now for thousands of citizens from Belarus who have been granted refugee status by the Polish government.

Tsimanouskaya herself had honeymooned there and Poland was also where she won her first race.

She was born in the small eastern Belarus town of Klimavichy to a father who is a fireman and a mother who works in a bank.

"Until the age of 13 I could not participate in any sports because of otitis media (illness that causes fluid to build up in the ear canal). I was deaf and suffered from a lack of balance. After a medical procedure I was fine and once I began to run, I never looked back," she says.

"At 15 I started a boarding school for athletes in Minsk where I lived on my own and at 18 became a member of the national team. By the age of 19, I was unstoppable," she says.

Athletes receive pampering from Lukashenko as he uses them to present his country as normative, but he also demands total loyalty from them.

Tell me how you were pampered?

"My husband and I lived in a nine square meter (29 foot) apartment. We shared a shower with one family and a kitchen with all nine apartments on our floor. If you cook something you must remain nearby, or your food will be stolen. You are given $200 dollars a month and sometimes an extra amount to purchase proteins for your diet. Most athletes also have a government job. I had a gun license and worked for the Interior Ministry, but the real money is in the international competitions."

After the August 2020 elections in Belarus when Lukashenko declared himself the victor, large protests broke out all over the country, claiming the election results were falsified. The regime responded by violently suppressing the protests and some 40,000 people were jailed, tortured and killed.

9 View gallery

Anti-government protesters in Minsk, Belarus call for the ouster of Alexander Lukashenko, claiming he falsified election results in October 2020

(Photo: MCT)

According to government testimony, dozens of protesters were crammed into a cell - big enough for 10 people - including COVID patients.

Approximately 1,000 athletes signed a petition calling for an end to the violence and new elections. All of them were jailed and tortured, thrown out of their respective teams and jobs, and had their salaries cut. Some lost their sanity, while others escaped.

Tsimanouskaya did not sign the petition but posted a story on Instagram calling for the violence to stop.

"Within 10 minutes there was a knock on my door, and I was asked to remove the post," she remembers. "I was in favor of the protests and thought that there was a momentum for change, but was not prepared to risk my family or my chances of competing in the Olympics," she says.

She did not remove the post and her monthly pay was cut in half. "I was then put on a blacklist which means I was not able to travel to competitions and make real money. That privilege was reserved only for those who were most loyal to Lukashenko," she says.

Was he afraid you would defect?

"Defection was not an option. Maybe he was afraid I would sit down with an Israeli journalist in Warsaw?" she says jokingly.

"At the start of the protests, there was a real sense of energy for change, but then the insane violence began and all you could see, hear and breath, was fear and the disgusting feeling that you could trust no one and that anyone could be an agent of the government," Tsimanouskaya says.

"I know in the end we will win. It is just a question of time and the number of victims. I know my role in the liberation of Belarus - I am a poster child, a symbol. But each and everyone of us must fulfil our duty. I also know that I will no longer stay silent. I understand that my words are inspiring to others," she says.

9 View gallery

Belarus police arrest anti government protestors during demonstrations in Minsk in October 2020

(Photo: AP)

Many Belarus athletes look at Tsimanouskaya with some skepticism. Some have blocked her on social media. They do not like the embrace of the Polish government and especially her relationship with Daniel Obajtek, a Polish oligarch with ties to the government, who owns the Polish national oil company and is currently working to cleanse his name in the local media.

Tsimanouskaya joined his conglomerate and is the presenter in a campaign for one of his companies. "I don't mix politics and spots," she says. "I am all about sports."

But some think she only replaced one dictatorship for another, less brutal one, and is a pawn in the power struggle between Poland and Belarus.

"Krystsina is a special case. She never showed any interest in the struggle," says Andrei Krauchanka, an Olympic medalist from 2008 who was jailed and tortured after signing the athletes' petition and who fled from Belarus to Germany. "But if you try to avoid politics in Belarus, it catches up with you," he says.

"At first I just wanted to be left alone," Tsimanouskaya says of the pressure put on her by fellow athletes to sign the petition. "Now I know they were right."

Tsimanouskaya has only just began to train again, mostly in her apartment. She jumps rope for 40 minutes a day, far from the five or six hours of training in Belarus.

"On the first week after I arrived in Poland, I could not train at all. I slept barely two hours a night and was shaking like mad all day. I couldn't hold on to anything, not even my food. I realized I no longer had anyone to rely on. Only myself.

Are you homesick?

"Very much so. I miss my family, where I trained, the places we would visit. Those are my memories."

What comes to your mind first when I say Belarus?

Tsimanouskaya folds her hands and shuts her eyes. Then she moves a hand and takes hold of her neck as if to strangle it. "I cannot breathe when I think of Belarus and that is almost all the time," she says.

Her freedom of movement is limited for security reasons, and also because she had been vaccinated against COVID-19 with the Russian Sputnik vaccine which is not recognized in Europe.

Everywhere she goes she wears large sunglasses to avoid being recognized. She is the flame that can reignite the Cold War. She is trying to obtain the necessary papers to be able to represent Poland in the next Olympic Games but may not succeed.

One thing is certain though, she will no longer be silenced.

Are you a closet rebel? You don't sign the petition, but you do post your story on Instagram. You won't join the protests but when you do stand up against your government you do so on the world stage in Tokyo?

"Maybe. I was always afraid of being kicked off the team before the games in Tokyo. That fear is gone."

You are called the symbol of freedom, but I do not see freedom in your eyes.

"Freedom is a relative term. Today I recognize the immense pressure that I had to live under, the physical and emotional demands that were made of me to show adoration and loyalty to the leader, while not even being provided with hot water or a private shower," Tsimanouskaya says.

"It is not easy to become a symbol of freedom. It is a difficult transformation. I wanted to be remembered for my running, but instead I've become the most remembered among the participants of the Tokyo Games for something else," she says.

"I've trained my whole life to run fast but I was never prepared for this. I know that if I participate in the Paris Games and win four gold medals, I will still be remembered for Tokyo - even though I hardly competed at all," Tsimanouskaya says.

I watched the games with my eight-year-old son. When I told him that I would be interviewing you he said that I was not going to interview an athlete but rather a hero.

Tsimanouskaya giggles with embarrassment as she moves uncomfortably in her chair and blushes. She is only an innocent young woman and it is difficult to see her as someone who embarrassed a loud and insane dictator.

"I never thought this would happen," she says. "If they had only asked me nicely – I would have run that race. But there are moments in life that if you remain silent, you choke. It is nice to hear that people think of me as a hero, but just one month ago I was no more than a good athlete. This is a bit too much for me, but I do understand the situation," she says.

"When the protests began, no one knew what the reaction of the government would be. I now understand the courage I had to take such a step when I knew full well what the regime's response would be. I hope this inspires a new wave of protests against Lukashenko.

You will be looking over your shoulder for the rest of your life, do you understand that?

"I am not afraid now, but I still walk around with six bodyguards. When they leave me, I will have to be careful of what I eat and drink and of opening my mail.

Would you have done anything differently?

"I would have posted the story on Instagram after the 200m race. Maybe I would have been less emotional, but I don't regret a thing."

We spoke for two hours. Double the time allotted for the interview. One of the guards signaled and pointed to his wristwatch, so we began gathering our gear and the security detail went into action.

Krystsina Tsimanouskaya looked around the room to make sure no one was watching and took a banana out of the fruit bowl. She quickly peeled it and ate it in small bites enjoying a sense of freedom, but still concerned that someone may be observing her. Just like her new life will be.