On the wall of the Erez Program’s workspace at Tel Aviv University hangs a large portrait of a tall officer with a thoughtful gaze, holding a short M16 rifle without a sling. This is Brig. Gen. Erez Gerstein, who was killed in Lebanon’s security zone on February 28, 1999. Gerstein, a former commander of the Golani Brigade and the Israel Defense Forces’ Liaison Unit to Lebanon, became a legend both in life and in death. The program is named in his honor.

In that same workspace, there is another corner of remembrance. A small table bears an Israeli flag, a single red rose, a wreath of white lilies, a memorial candle, and a photograph of a saluting soldier. This is 2nd Lt. Itay Yavetz, a trainee in the Erez Program who had reached an advanced stage of the course. He fell in battle in Rafah last month while attached to the Nahal Brigade. The next day, he was supposed to leave Gaza and begin his second year of academic studies.

Now, as his fellow cadets sit with their laptops in the shared workspace or make coffee in the espresso machine in the kitchenette, Yavetz’s photo — much like that of Gerstein — reminds them why they are here, and why they chose to devote three and a half years of their lives to becoming officers in the IDF’s Ground Forces.

Another fallen soldier’s presence hovers above them as well: Sgt. Guy Bazak, who was killed on October 7 in the battle for Kibbutz Kissufim. His father, Brig. Gen. (res.) Yuval Bazak, a lifelong Golani officer, has led the Erez Program since its inception. When Gerstein commanded the Golani Brigade, Bazak served under him as commander of the 51st Battalion. His son, Guy, followed in both their paths and served as a fighter in the same battalion. The first cohort of Erez cadets — including Yavetz — attended Guy’s funeral.

On October 19, the day Yavetz was killed, I attended the completion ceremony for the younger Erez cohort’s Commando training, held at the Har’el Brigade memorial in Har Adar, in the Jerusalem Hills. Before the ceremony, the soldiers planted cedar trees on a nearby hill. One of the program’s staff members pulled me aside and whispered, “I assume you’ve heard that two soldiers fell this morning in Rafah. Don’t say anything yet — the guys here don’t know, but one of them is from Erez’s senior company.”

'Our role, as the Erez Program, is to go through this together. Part of being a combat commander — as Erez Gerstein taught us — is learning to cope with loss: to accompany and embrace the families, to take care of your soldiers, and to continue leading them forward.'

After the tree planting, Bazak delivered a short address, concealing his inner turmoil. “I wish for all of us to see these trees grow and flourish, just as you will grow and advance through the IDF’s command ranks,” he said in closing.

Even during the ceremony held later at the foot of the memorial — before the emotional young cadets in their red berets and their equally emotional parents — the speakers carefully avoided revealing what could not yet be made public.

At the end of the event, company commander Maj. M. called forward two cadets who had started the program in the senior cohort but transferred to the younger one after being injured. They had personally known Yavetz. “When we heard he’d fallen, I was in shock,” recalls Sgt. N. “Just a few weeks earlier, a friend of mine who had been with me for two years in the Ali pre-military academy, Lt. Itay Ben-Itzhak, was killed in Rafah. A year before that, in Lebanon, Capt. Ben Zion Falach, who was with me for three years at the military boarding school in Haifa, was killed. And now, Itay too. I’m tired of hearing about friends being killed.”

When Bazak noticed one of the cadets who had known Yavetz sitting off to the side, crying as his parents tried to comfort him, he approached and embraced him. Later, he spoke of what he was feeling: “When I lost Guy, it was at the very start of Erez’s first class. Parents came up to me and said, ‘You’ve lost a son, but you’ve gained sixty new ones.’ And today, I feel like I’ve lost another. It’s a connection of more than two years — a deep, personal bond.

“Our role, as the Erez Program, is to go through this together. Part of being a combat commander — as Erez Gerstein taught us — is learning to cope with loss: to accompany and embrace the families, to take care of your soldiers, and to continue leading them forward. That’s what we do with our cadets. They are a very strong, cohesive group, and I’m certain they’ll only grow stronger through this.”

He speaks from experience — not only as a bereaved father but also as a soldier who has lost friends. “Five months before October 7, on Memorial Day, I went with Guy — his first time in uniform — to visit the families of my fallen comrades,” he recalls. “We went to the Eliel family in Kfar Tavor, to the family of Lt. Col. Hussein Amir in Julis, and to the Gerstein family in Kibbutz Reshafim. I wanted him to know their legacy. I never imagined that so soon afterward, he would become part of those same photos on the wall, and that we would go from being comforters to being the ones comforted. But that’s life — it’s not ours to choose. What we can choose is how to face it.”

Creating the elite combat officer

It’s not easy to define exactly what the Erez Program is. One could call it the “Flight Course of the Ground Forces” — though in fact it’s longer, spanning three and a half years, including officer training. It could also be compared to West Point, the U.S. Army’s prestigious academy for future commanders. Yet neither comparison fully captures what it is.

As stated on the memorial plaque for Brig. Gen. Erez Gerstein, the program “identifies and trains exceptional recruits with high leadership potential, preparing them for service as platoon and company commanders in the IDF’s ground combat units. It combines comprehensive military training with academic study, emphasizing leadership, professionalism, and love of the land — values that defined Erez Gerstein himself.”

'During our first two days here, almost every lecturer opened the class by saying, “Can someone explain what this many soldiers are doing here?” recalls Sgt. N. 'Then you spend fifteen minutes explaining what the Erez Program is.'

The first class, known as Itay Company, began in September 2023 and continued its track even after the war broke out. The second cohort, Barak Company, started a year later, and the third has just taken its first steps. Candidates are selected through the army’s elite unit screening days and special tryouts. Even before their official enlistment, they complete a three-month pre-military phase known as Kadatz, during which they take Israel’s psychometric exam and get their first taste of military life.

The next phase is basic infantry training at the Golani Brigade’s training base. From there, they move on to the Commando School at the Adam base, where they undergo an eight-month course alongside the training companies of Egoz, Maglan, and Duvdevan.

“The cadets acquire all the professional tools of an elite combat soldier — solo navigation, counterterrorism, and more,” explains Lt. Col. A., commander of the Erez Unit (the program has a civilian directorate headed by Yuval Bazak and a military command structure). “The commando training includes six special ‘Erez weeks’ unique to the program, covering subjects like leadership, command of armored vehicles, explosives, and operational deployment.”

At the end of their first year, they are already certified as squad commanders. They then begin their academic degree at Tel Aviv University. Unlike regular students, Erez cadets remain under full military framework. They live on two dedicated floors of the student dormitories, wear uniforms — even in class — and their days include roll calls and fitness sessions.

“During our first two days here, almost every lecturer opened the class by saying, ‘Can someone explain what this many soldiers are doing here?’” recalls Sgt. N. “Then you spend fifteen minutes explaining what the Erez Program is.”

Their studies are condensed into two years instead of three, making them extremely intensive. The degree is dual-track: general studies in the humanities with a focus on military and security topics, and a second major chosen from four options — management, Middle Eastern studies, political science, or digital sciences for high-tech.

Their first semester break is dedicated to advanced certification courses in a range of fields: two and a half weeks at the School of Firepower in Shivta, two and a half weeks at the Armored Corps School, and one week at the Combat Engineering School. During the summer break, they already know where they’ll be posted as future platoon commanders, and each cadet spends a month attached to the unit where he will eventually serve. At this stage, they exchange their red berets for those of their assigned brigades or corps. Cadets designated for armor, engineering, or artillery undergo professional command courses specific to those branches.

After this stage, they begin their second academic year, during which they periodically join their future units for on-site training. Three years after enlistment, they move on to the officers’ course.

Hard-earned stripes

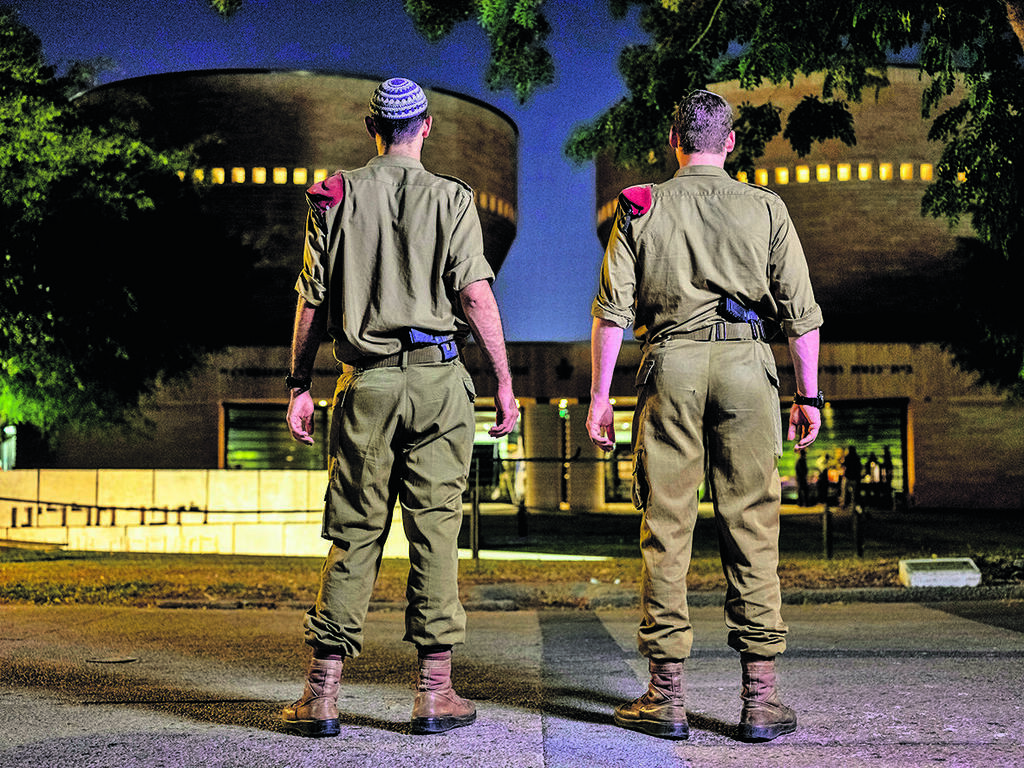

At the start of the current academic year, a moving ceremony was held at Tel Aviv University’s Cymbalista Synagogue and Jewish Heritage Center. There, the team commanders presented the three-stripe tags to the senior cohort — now officially named Itay Company — who in turn presented the two-stripe tags to the younger Barak Company, which had completed commando training and begun its first year of studies.

'There were cadets who left because they wanted to go fight,' says Lt. Col. A. 'I deeply respect that urge. I tell him, "There will be plenty more wars in our neighborhood." But he wants to go now — and I can’t stop him. We’re a volunteer unit'

Sgt. A., a friend of Itay Yavetz from his company, spoke on behalf of the cadets. A 22-year-old from Jerusalem, wearing the beret of the Kfir Brigade — where he served for a month in Gaza and will return as a future platoon commander — he told the audience, “This year, there’s a pair of triple-stripe tags that were earned with full merit but will never be worn. We will remember and honor Itay’s spirit, and let it guide us from now on — his joy, his firm principles from the back row in the Gilman building classroom, his desire to be with the team even when his arm was broken, even when things were hard.”

On the wall behind him, a slideshow of photos from Itay’s training played. “When we planned this ceremony, we thought there would be a hundred warriors here,” Bazak told the cadets — ninety-nine in total. “And the truth is, there are. Itay is still with us — in training, in workouts, in class, in our hearts. My son Guy was very much like Yavetz — mischievous, full of spirit, a natural leader — and people like them never disappear. They continue to live in our hearts, to be present, to inspire.”

Yavetz had been attached to the Nahal Brigade’s 932nd Battalion and was killed by an anti-tank missile alongside his company commander, Maj. Yaniv Kula. Two days later, I met his fellow cadets at the Adam base, where they had come to return their combat gear after completing their attachments to operational units and before resuming classes at the university. The first time they had met again as a company since deployment was at Itay’s funeral.

Sgt. A., 22, from the Hefer Valley, says the tragedy only strengthened his sense of purpose. “Itay is deeply missed, but it pushes me to continue, to excel, and to fulfill the mission I came here for — to lead people in battle.”

“Sitting in class on Memorial Day and Itay isn’t with us, going to the university and he’s not there — it’s strange,” adds Sgt. A.N., 20, who lives in a moshav in the western Negev. “But we all know that despite the pain, we have to move forward in his spirit, to push harder. He’s with us, even if he’s not physically here.”

Like Itay, A.N. is assigned to the Nahal Brigade. He spent his attachment period with the 931st Battalion in Gaza as part of Operation Gideon’s Chariots II. Sgt. A., slated for Kfir, fought in Gaza with the “Leopard” Brigade and later helped hold the “yellow line” near Khan Younis during the cease-fire. Sgt. A.G. is headed for the Paratroopers’ 202nd Battalion and spent his deployment on the line in Hebron. “At first, we were disappointed not to be sent to Gaza,” he admits, “but in the end it paid off — the level of friction there was very high, and we did things you don’t usually touch during training. When you’re shadowing a platoon or company commander, you really understand what it means to lead in combat.”

Their attachments weren’t their first taste of real operations. During training, they had already taken part in missions in the West Bank, entered Gaza, and even joined an arms-search operation in Lebanon with Golani’s 12th Battalion.

A bullet to the chest, above the vest

For cadets who began their training just before October 7, the shadow of war has never really lifted. Many felt frustrated at sitting in university classrooms while their friends were fighting at the front.

“There were cadets who left because they wanted to go fight,” says Lt. Col. A. “I deeply respect that urge.”

What do you tell a cadet like that?

“I tell him, ‘There will be plenty more wars in our neighborhood.’ But he wants to go now — and I can’t stop him. We’re a volunteer unit.”

A.N. understands that feeling. “During my first year at the university, I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue,” he says. “It felt like I wasn’t in the army for this — people you know are out there fighting, and you want to join them, to contribute your part. But in the end, you realize the purpose of the program: that you need to go through a certain path to reach the place you’re meant to be.”

Almost all of the program’s commanders have fought in Gaza and Lebanon. One of them, Capt. Yahel Gazit led one of the Kadatz teams. On December 4, 2024, he was killed in Gaza while serving as a deputy tank company commander in the 188th Brigade.

'At one point, I was hit in the chest, just above my ceramic vest,' he recounts. 'I managed to fire a few more shots before collapsing. The deputy battalion commander who was with me was also wounded. Our rescue and evacuation were an act of heroism'

The previous head of the academic phase — who oversaw the cadets during their university studies — was Maj. A., deputy commander of the Paratroopers’ 101st Battalion during the first year of the war. His successor grew up in Golani’s reconnaissance unit, fought in the Iron Swords war as a reserve officer in the brigade, and returned to permanent service afterward.

The commander of Erez’s younger company, Maj. M., is also a Golani officer. On October 7, he was stationed at the Kissufim outpost as the operations officer of Battalion 51. When the terrorists broke in, he ran out to fight. “At one point, I was hit in the chest, just above my ceramic vest,” he recounts. “I managed to fire a few more shots before collapsing. The deputy battalion commander who was with me was also wounded. Our rescue and evacuation were an act of heroism.”

He spent a month hospitalized at Soroka Medical Center and another eight months in rehabilitation at Hadassah Mount Scopus. “I came straight back to this role,” he says. “My victory is returning to the army and training the next generation of commanders.”

The commanders’ combat experience is not just a bonus — it’s a cornerstone of the training. “My team commander served in Yahalom during the war and worked closely with many units in Gaza and Lebanon,” says Sgt. Y., 21, from Barak Company. “He brings us incredible firsthand knowledge — real, relevant lessons. Sometimes he’ll say, ‘Yes, that’s the doctrine, but on the battlefield, it doesn’t always work like that.’ The same goes for Maj. M., our company commander, and all the other officers.”

Y., like six of his peers, originally enlisted in the Armored Corps. “At the end of basic training, I was named outstanding trainee and offered a transfer to Erez,” he says. “We also have guys who started in Kfir, Nahal, and Givati. Everyone who came from another unit is meant to return to it as an officer.”

Sgt. N., another cadet, has a story of his own. He and his twin brother — identical twins — attended the Haifa military boarding school together, then a pre-military academy, and finally enlisted together in the first Erez cohort. Half a year in, during the parachuting course, N. was injured and shattered his leg. After eight months of rehabilitation, he returned to Erez, joining the younger company instead. Their mother, whose identity cannot be revealed here, once appeared as a teenager in one of the most iconic photographs in Israel’s history.

Staying awake in class

Although the younger company’s cadets wear red berets and boots, the spirit of the Golani Brigade looms large in the program. Gerstein commanded the brigade; Bazak was once its deputy commander; and his deputy in the program’s civilian directorate, Col. (res.) Idan Galili, served as Golani’s personnel officer during the Second Lebanon War under then-brigade commander and now deputy chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Tamir Yadai.

Galili was the one who conceived the program and pitched the idea to Yadai upon his appointment as head of the Ground Forces Command. Yadai — who, as a young lieutenant in Golani, had served under Gerstein when he was a battalion commander — decided to name the program after his revered mentor.

Gerstein’s legacy is an inseparable part of Erez. “At the start of training, every cadet receives a copy of Udi Eiran’s book Essence of Longing: The Story of Erez Gerstein and the War in Lebanon,” says Sgt. A. “Each year, we have an ‘Erez Day,’ when we visit Kibbutz Reshafim, meet people who knew him, and attend his memorial service. At the entrance to our compound at the Adam base, there’s a sign bearing one of his quotes: ‘Those who don’t want to win shouldn’t participate.’”

That spirit carries into their daily life. “Just yesterday, we had a conversation with our training commander,” A. says. “He told us that even at the university, we should act according to Erez’s values. ‘If you’re nodding off in class or checking your phone,’ he said, ‘ask yourself if that fits or doesn’t fit the image of Erez Gerstein.’”

After Bazak’s personal tragedy, his son Guy’s legacy has also become part of the program’s ethos. “He took the entire company to Kissufim and taught us the full story of his son’s battle,” says A.N. “We walked through all the places where Guy fought until he fell.”

Sitting with Bazak at a picnic table in the Har’el Brigade memorial site, just hours after he lost one of his own cadets, he told me what his son’s legacy means:

“Fifteen guys left the outpost — barely ten months into their service — running straight into the fire, outnumbered and outgunned. Guy went out without even body armor, and with their bare hands they stopped what could have been a far greater massacre at Kibbutz Kissufim.

“Guy was the team marksman. He spotted the terrorists entering from the southern gate and opened fire. In the combat debrief, Hamas radio transcripts revealed they’d been stuck for an hour, unable to move because of a sniper who killed four of them and wounded several more. That sniper was Guy.

“When I arrived at Kissufim after October 7 and went to the position where he’d been, I saw 30 or 40 spent casings on the floor and imagined that boy loading and firing them one by one, holding back a Hamas squad. Later, the second wave came from the northern neighborhood, and they fought house to house. Guy was up front with his partner, who got wounded, and Guy treated him under fire — then charged forward and was hit by a burst, a bullet straight to the heart.

“What kept his friends going in those impossible hours were professionalism, brotherhood, and the spirit of Golani. And those are the values we’re passing on to the next generation of commanders.”