It’s easy to get lost on the way to the illegal Nahalat Zvi outpost if you're unfamiliar with the area, and reaching it by private car is no simple task. “We’re still working on it,” locals explain. After entering the settlement of Maale Michmash, northeast of Jerusalem, a dirt path leads to an electric gate. “Call and we’ll open it,” said Da‑El, 27, a resident of the outpost. “Just wait until it closes before you drive on, we don’t want anyone coming in who shouldn’t.”

Beyond the gate, a rocky trail climbs uphill. “That’s the hard part,” Da‑El said. “If you can make it up the hill, you’ve earned the view of Nahalat Zvi.” A push on the gas pedal, a short burst of speed, and the vehicle arrives at the hilltop outpost.

Just yesterday, ynet and Yedioth Ahronoth revealed large government budgets being funneled across the Green Line. But beyond the money, the current government’s approach to the West Bank — led by Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, National Missions Minister Orit Strook and their allies — is already felt on the ground.

Nahalat Zvi, named for Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, is a relatively rare sight in the settlement enterprise and a clear example of the shift underway. Its founders are religious Zionists from Jerusalem’s Mercaz Harav yeshiva. Most did not grow up in the West Bank and still study full time in Jerusalem. “We saw the Nachala Movement’s campaign to build new settlements and said, let’s build our own,” said Yishai Shachor, 25, a father of two living on the hilltop.

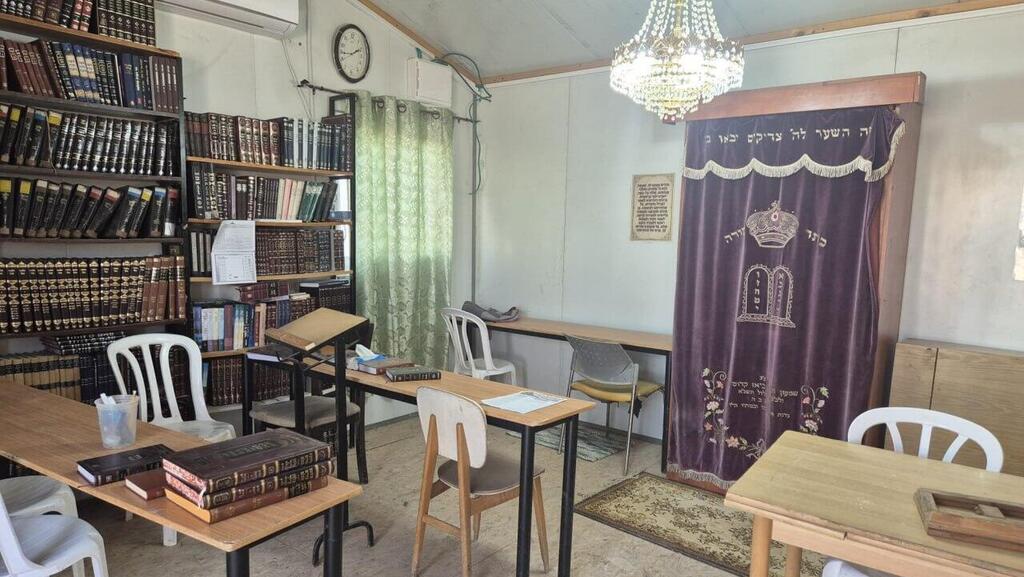

I met Da‑El and Yishai met at the entrance to the outpost synagogue. Sitting on plastic chairs under the open sky, Da‑El poured coffee and brought out cookies his wife had baked. “The yeshiva held discussions about choosing the site,” he recalled. “We respect everyone involved in settlement activity, but we have our own approach. We didn’t look for illegal spots or Area B land — only state land that can be regularized. We’re not looking for trouble. We wanted something close to Jerusalem because of our studies.”

“We gathered building materials, furniture and donations, and came up here during Sukkot of 2022, right after Simchat Torah,” Yishai continued. “Thirty of us arrived at night. There were goat droppings everywhere. This place was unrecognizable. We carried all the building materials on our shoulders for nearly an hour, up and down hills. What you just drove, they walked.”

It’s at this point that Yishai’s story highlights the changing reality on the ground. “Three days after we arrived, the army came and confiscated our tents and issued a monthlong closed military zone order,” he said. Benny Gantz was defense minister at the time, and orders were clear. “We took shifts to maintain a constant presence. People rotated in and out. Every time we were evacuated, we came back the same day. We went through at least ten evacuations.”

During that period, enforcement was tight. “Inspectors from the Civil Administration were here constantly putting up cameras, flying drones, checking who was around. The army too. We were under a magnifying glass. Then, one day, it just stopped. It was hard to believe. They used to come with stop-work orders. They took our equipment, trucks, tractors.”

According to Yishai, the turning point came after the new government took office. “There was one last eviction we didn’t understand, but then the evacuations stopped. Normally they’d remove us after three or four days. Sometimes five. Suddenly, the forces didn’t come. The buildings stayed. Days passed and no one came. We could finally breathe, and slowly, we brought more structures.”

Nahalat Zvi sits on state land at a strategic point that disrupts potential Palestinian territorial continuity. But a legal source assisting Palestinians in the area claims that while the buildings themselves are on state land, the road leading to them crosses private Palestinian property. “This is how they remove Palestinians off the land. It’s de facto annexation,” the source said.

The shift experienced by Mercaz Harav students in the field reflects a broader policy transformation taking place in Jerusalem. The government is no longer dismantling unauthorized outposts but allowing them to expand and preparing them for formal recognition, as seen with the so-called “young settlements” (dozens of outposts approved through an expedited process).

Smotrich’s efforts extend beyond outpost legalization. More than 120 agricultural farms have been established across the West Bank, and thousands of dunams have been declared state land. In the past, a place like Nahalat Zvi would never have gotten off the ground.

Now, enforcement has all but disappeared, and settlement activity is expanding at an unprecedented pace.

“It’s a miracle that looks like nature,” Da‑El said. “This isn’t the parting of the Red Sea or fire from the heavens — it’s spirit and faith.