Chapter 1: The nightmare scenario

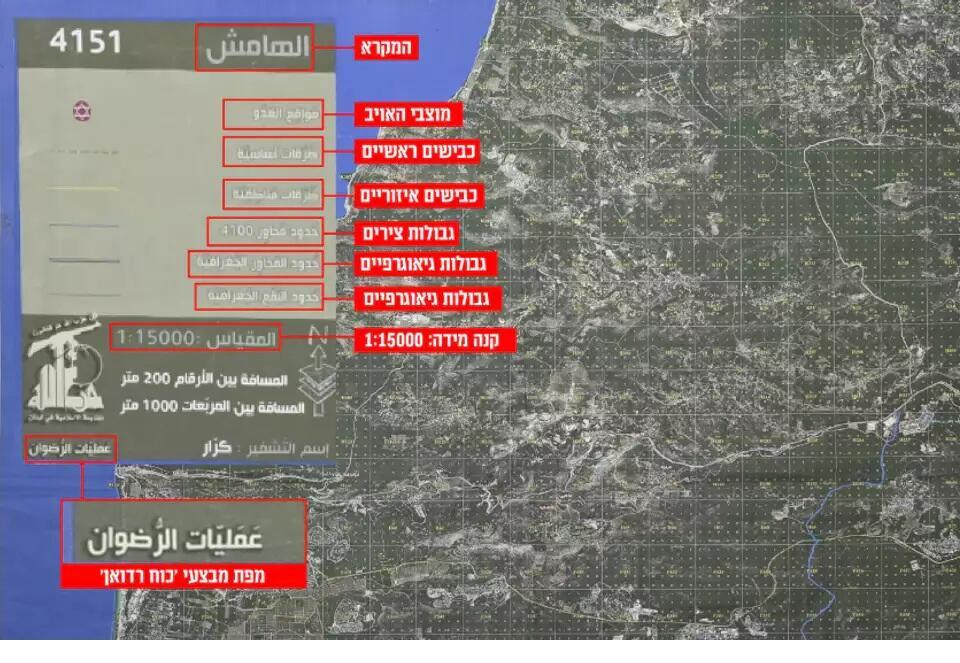

Beneath the ground, within touching distance of family homes in the northern Israeli towns of Metula, Shtula and Nahariya, the clock was already ticking backward. Inside tunnels dug close to the border fence, the transition to combat readiness was swift. Thousands of Hezbollah terrorists who had entered roughly 30 border villages minutes earlier dressed in civilian clothes and sandals were now sealed inside full combat gear. Fifteen reduced-size elite battalions known as “fouj,” together numbering about 3,000 Radwan Force commandos, some of them veterans of the Syrian civil war, stood ready. They knew the activation order could arrive at any point within the next six hours.

On shelves around them, wrapped in sterile plastic packaging that would not have looked out of place in an Israeli military emergency depot, waited the tools for the slaughter ahead: lubricated assault rifles, loaded magazines, encrypted radios and even refrigerators stocked with blood units for immediate transfusion to wounded fighters. Shortly beforehand, the assault had begun without warning. Massive barrages of hundreds of rockets per minute pounded every strategic point along the border, while precision sniper fire and anti-tank missiles methodically destroyed surveillance cameras and sensors embedded in Israel’s northern concrete barrier. Then the ground shook.

Under cover of the chaos, they broke through. Hezbollah did not need the cross-border tunnels Israel had destroyed in a 2018 operation. Instead, Radwan fighters emerged from proximity tunnels ending just short of the fence, where explosive charges had already been prepared. The charges were attached and detonated, collapsing sections of the barrier. Through the breaches, the Radwan Force poured in, not in small cells but as an invading army advancing on five axes designed to sever the Galilee region from the rest of Israel.

One brigade sped toward Nahariya. Only seven kilometers separate the coastal city from the border, and no natural obstacles stood in the way. From the sea, about 150 naval commandos arrived in fast boats, landing on the city’s promenade with one goal: abduct as many civilians as possible to use as human shields and deter Israeli airstrikes in Lebanon. A second brigade encircled the town of Shlomi, whose roughly 9,000 residents woke to find their community, just 300 meters from the border, under occupation. A third brigade cut Israel’s main northern artery, the Acre-Safed highway, advancing toward the city of Karmiel. A fourth seized the Ramim Ridge, capturing the border communities of Malkiya and Yiftah to prevent Israeli artillery from firing into Lebanon.

A fifth brigade, a reserve force, waited for instructions coming directly from Iran. Would they push toward the Acre-Haifa road? Attack oil refineries in Haifa Bay? Strike the port of Haifa or the airfield at the Technological College in the city? Above, swarms of explosive drones, including some launched from Iran and Yemen, buzzed toward Israeli bases and reinforcement hubs rushing north. Rocket fire did not let up. In the first 46 hours of the attack, about 16,000 rockets were fired. Inside the captured communities, resistance was minimal. Many members of local civilian emergency squads had no weapons available, not even in locked armories. Terrorist cells barricaded themselves inside homes with surviving hostages. Snipers established concealed positions, while others, armed with anti-tank weapons, set ambushes. They waited for Israeli rescue forces they knew would eventually arrive.

On televisions flickering inside bullet-riddled living rooms, unimaginable images appeared. Radwan terrorists racing almost unhindered along the Acre-Safed highway past burning vehicles. Yellow Hezbollah flags flying over Nahariya’s fishing pier and the cedar monument at Shlomi’s entrance. Alongside them, live footage from Israel’s south showed burning communities and terrorists roaming the streets of Sderot and Ofakim. The Israeli military activated its northern emergency plan. Most units rushed north had trained primarily for ground maneuvers inside Lebanon, not for fighting to retake Israeli towns. Some had rehearsed scenarios involving one or two captured communities, but no one had prepared for the collapse of an entire border line.

Soldiers tried to reach emergency depots to collect weapons, armored vehicles and equipment. Some were killed en route at intersections already controlled by Hezbollah units. Those who made it found depots burning or already captured. Even the headquarters of Israel’s Galilee Division, located at Camp Biranit on the border, fell. Troops stationed along the fence, long instructed to “keep the sector quiet,” lacked both equipment and training to limit the devastation. Hezbollah’s Radwan fighters, by contrast, were highly organized, well trained and heavily armed.

About 48 hours after the initial breach, another 5,300 Hezbollah terrorists from regular and reserve units poured through the widened gaps in the barrier. This was the second wave. Though less elite than the Radwan Force, they were well equipped. Due to Hezbollah’s strict compartmentalization, they had received their assembly orders only hours earlier. They expanded the occupied territory and intensified resistance against Israeli forces. Around captured towns and along key routes, Hezbollah fighters planted roadside bombs, mines and anti-armor charges, supported by observation posts and sniper fire. Their intention was clear: hold the territory “liberated” inside Israel to the last drop of blood.

The Israeli Air Force struggled under these conditions. Pilots and drone operators were trained to strike strategic targets and conduct targeted assassinations across the border. Bombing a dairy farm because terrorists might be hiding inside, or a guard booth at the entrance to an Israeli town, was another matter entirely. Israel’s limited attack helicopter fleet was forced to shuttle constantly between the southern and northern fronts.

Only after many days, and at a staggering cost, did Israeli forces regain control of the Galilee. The death toll climbed into the thousands. Tens of thousands were wounded, some still trapped in the field and pleading for rescue. Hundreds of Israeli hostages, including soldiers captured at overrun bases, were taken across the border. Some were dispersed throughout southern Lebanon and Beirut as human shields. Israeli intelligence later learned that several captured officers were being brutally interrogated by Iranian personnel at facilities in Syria.

This scenario is not fictional. The core elements of Hezbollah’s plan to conquer the Galilee were known to the Israeli military long before October 7. Parts of it were published in Lebanese media as early as 2011. Hezbollah is an organization deeply penetrated by Israeli intelligence, and the disclosures likely did not surprise analysts specializing in Lebanon. Yet on that terrible Saturday, Israel was unprepared for such a scenario. What prevented it from becoming reality was a single phone call from Tehran.

More than two years have passed. The detailed, realistic scenario described here did not materialize. After a brutal war that exacted a heavy toll, it was removed from over the heads of hundreds of thousands of northern residents. Hezbollah suffered a severe blow. Its leaders were killed, its weapons stockpiles diminished. In the meantime, countless words have been written about the chain of failures that led to the catastrophe in Israel’s south. Somehow, the failure along the northern border, where a massacre potentially far worse than October 7 was narrowly avoided, faded from public view.

No one was held accountable for the exposure of the Galilee. The investigations the Israeli military conducted into the northern front that day were not presented to the public. Most were never published. No senior officer was summoned to explain why northern Israel was left so vulnerable.

The military says lessons were learned and the security concept along the northern border has changed completely. Still, the October 7 failure in the north remained in the shadows until now. “It was clear to everyone that if something started here in the north, it would be a mass slaughter. We saw what Hezbollah had prepared for us,” a reserve officer told ynet “We had a miracle from heaven.”

Over recent weeks, we spoke with military officers, intelligence analysts and security officials deeply familiar with conditions along the northern border before October 7. The word “miracle” came up repeatedly, and not sarcastically. When one dives into the depth of that day’s failure, it becomes clear why. It also becomes impossible to ignore the reality: Israel’s security establishment knew what could happen in the north and simply did not prevent it. Now, more than two years later, the time has come to understand exactly what happened there.

Chapter 2: The northern concept

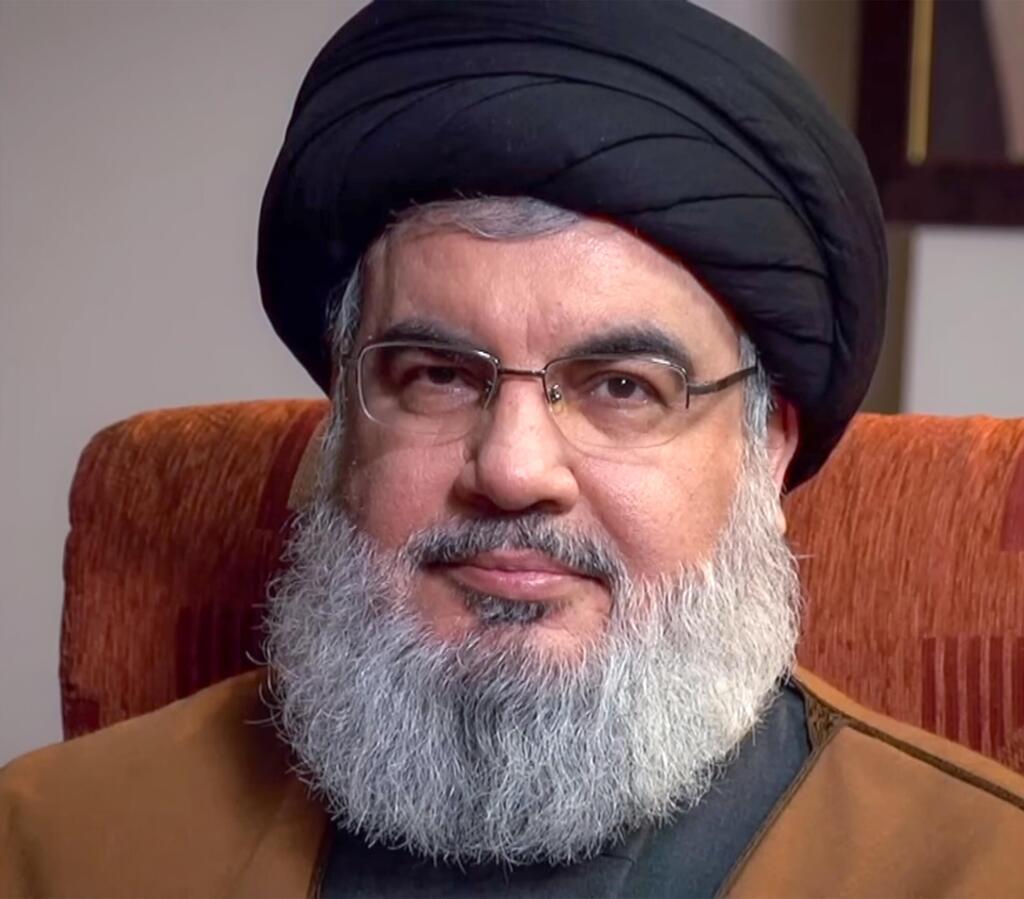

Hezbollah’s invasion plan was developed under Iranian guidance years before what many now call a miracle. The plan has existed since at least 2011. Since then, Israel has had three prime ministers, five defense ministers, dozens of Cabinet members, three chiefs of staff, four heads of Northern Command and hundreds of senior security officials. None prepared the system for a mass invasion. All were convinced Hezbollah’s threats were psychological warfare and that its leader, Hassan Nasrallah, would not risk Lebanon by launching such an attack. And if he did, Israel would receive early warning and stop it.

This was the “northern concept”: Hezbollah was deterred and would not go to war. If it attacked, Israel would know in advance and respond. But on October 7, Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar launched an attack in the south without coordinating the exact timing with Nasrallah, who was surprised and perhaps offended. For his own reasons, Nasrallah joined the fighting the next day in a limited way, without activating the full invasion plan. Had he decided otherwise, or received a different order from Iran, Israel would likely have faced a far greater collapse than what unfolded in the south.

This was no secret. Responsibility lies with both the political and security leadership, all of whom will eventually face a state commission of inquiry, one the government has worked hard to avoid establishing. Among the intelligence officials long familiar with Hezbollah’s plan was Brig. Gen. (res.) Shimon Shapira, a former senior officer in Israel’s Military Intelligence Directorate. “They would have abducted and slaughtered, and we would have had exactly what we saw in the south, only far worse,” he told ynet.

Shapira, who has followed Nasrallah for 40 years and authored a book on Hezbollah, said the operational plan to conquer the Galilee was formulated in early 2011. “I learned about it on October 27, 2011, in the Lebanese newspaper Al-Joumhouria,” he said. “It wasn’t secret.” According to the report, Nasrallah instructed commanders to prepare for a scenario in which Hezbollah would fire rockets at Tel Aviv at the start of the next war while simultaneously sending forces to seize the Galilee. The source emphasized this was an operational directive, not psychological warfare. Hezbollah did not deny it.

In late 2011, about 5,000 Radwan Force terrorists were sent to Iran for intensive training. Each battalion studied the specific terrain it was assigned to conquer. The Syrian war interrupted training but provided extensive combat experience. In December 2018, Israel destroyed six cross-border tunnels. Then-Chief of Staff Gadi Eisenkot confirmed Hezbollah had planned to infiltrate 5,000 fighters underground while launching heavy fire. The tunnels were lost, but the idea of conquering the Galilee was not abandoned.

Those meant to defend the communities until military forces arrived were members of the local emergency response squads. In the north, however, a wave of weapons thefts led to a decision to take firearms from most of them and store the weapons at the regional brigade base. This was the logic before October 7: an emergency squad member would hear that Radwan Force units were racing toward the community, drive to the base to arm himself and only then return to fight for his home

Nasrallah continued to threaten publicly that Hezbollah would capture Israeli towns in any future war. Meanwhile, the group invested heavily in digging attack tunnels that stopped short of the border, planning to breach the barrier with explosives instead. In early 2023, retired Lebanese Gen. Hisham Jaber described how a Hezbollah ground assault would begin, warning that Israeli air power and tanks would be largely ineffective once terrorists embedded themselves among Israeli civilians.

When Israeli forces later maneuvered in southern Lebanon, they uncovered countless infrastructure sites stocked with weapons and equipment for thousands of fighters awaiting orders. Nearly every home in some villages contained arms. Pharmacies, orchards and garages concealed rockets, mortars, explosives and launchers, along with detailed maps of Israeli targets. During ground operations, Israel seized more than 85,000 weapons and intelligence items, including thousands of rocket launchers, explosives, anti-aircraft missiles and vehicles. Military officials stressed this was only a fraction of what existed. Now imagine all that weaponry carried by 3,000 Radwan fighters and more than 5,300 additional Hezbollah operatives crossing into Israel.

Chapter 3: Who deterred whom?

The Israeli military may have been shocked by the scale of Hezbollah’s weapons stockpiles, but not by the intent behind them. One month before Hamas’ attack, on September 7, 2023, Israel’s Northern Command held a special conference on preparations for the next war. Hezbollah had already escalated provocations, including drone infiltrations, a deadly roadside bombing near Megiddo and the establishment of tents inside disputed territory near Mount Dov.

Each incident could have justified a severe Israeli response. Instead, officials repeated the familiar refrain: Hezbollah was deterred and did not want war. Only a few senior officers dissented. Col. Uri Dauba warned that if Hezbollah attacked, it would breach all defenses and capture bases and towns, and existing forces would not stop it. His warning went largely ignored.

Others raised alarms. A former division commander clashed with then-intelligence chief Aharon Haliva over insufficient forces. Haliva dismissed concerns, saying that without warning, the entire General Staff could resign. A classified State Comptroller report completed months before the war warned of severe readiness and equipment failures along the northern border. It was not acted upon. Some officers tried to improvise solutions, forming local rapid-response units with minimal support. They knew it would not be enough. “We were gambling,” admitted one senior intelligence officer. “The system believed blindly in warning intelligence. Civilians asked one simple question: what if intelligence fails? We had no answer.”

Chapter 4: Emergency squads without weapons

Facing all the forces Hezbollah could have deployed into Israel within six to 48 hours, roughly four IDF battalions were spread along the border with Lebanon. On paper, this was a sizeable force, some 3,500 to 4,000 soldiers. In practice, on October 7, there were far fewer troops because of the holiday leave. The element of surprise, combined with rocket barrages and drones, would have impaired the operational readiness of many of them. They were also neither trained nor prepared to contend with the extensive attack plans Hezbollah had devised inside Israel.

Radwan forces, along with more than 5,300 additional terrorists slated to arrive in the second wave of the assault, were meant to operate in a focused manner, sector by sector. All four battalions were stretched across about 130 kilometers (80 miles) of border, in mountainous terrain. By comparison, the Gaza front has just 59 kilometers (37 miles) of border, in relatively flat terrain.

Why only four battalions? Lt. Col. (res.) Meir describes years of erosion in the order of battle deployed along the Lebanese border, in part because of constraints on other fronts and a shortage of combat manpower in the IDF. “The main thing that concerned me in those years was the number of fighters on the fence,” Meir says. “Little by little, I saw how the army went from holding 12 battalions on the Lebanese front to eight, seven and six. Every year they cut a battalion, until by 2023 we were down to just four battalions of fighters along the entire Lebanese front. That force structure is a joke for a border of about 130 kilometers. I have no other word for it but ‘shame.’ Every senior commander at the highest levels should have stomped their feet and done something about this, but IDF commanders waited and hoped that nothing would happen on their watch, and showed us in presentations that everything was fine.”

According to the IDF plan, the forces meant to deal with a ground assault on the communities until IDF reinforcements arrived were the local standby squads. But unlike in the south, where members of the standby squads fought bravely and in some cases even prevented terrorists from entering their communities, in the north only a few members of the standby squads had access to weapons. Where were the weapons? In some cases not even in an armory, but at the regional brigade base. The reason was a wave of weapons thefts in the north. That was the pre–October 7 logic: a standby squad member would hear that a Radwan cell was on its way to the community, then drive to the regional brigade base to arm up, and only then return to defend his home.

“At seven in the morning on October 7, when I saw the reports about what was happening in the south, I asked myself, where is Hezbollah?” recalls Dotan Ruchman, head of the security and emergency department at the Upper Galilee Regional Council. “In my mind there were two possibilities: either they were simply delayed by an hour, or they were already past Rosh Pina and didn’t need to fire a single bullet to advance. By 7:30, standby squads with only a handful of weapons were already waiting for Radwan.”

In the town of Shlomi, council head Gabi Naaman says, the first soldiers arrived only toward 5 p.m. A few kilometers east, in the border moshav of Shomera, Eliezer Amsalem, head of the emergency and security department at the Ma’aleh Yosef Regional Council in the western Galilee, watched television anxiously. “God loves us. It’s an open miracle that Hezbollah didn’t break in here first,” he says emphatically. “We had no ability to deal with them in our communities.”

According to Hezbollah’s plan, the first wave of terrorists was to split into five elements: one brigade would race toward Nahariya, including a naval commando force that would land along the promenade and focus primarily on kidnappings. A second brigade would seize Shlomi, a third the Ramot Ridge (and neutralize the artillery deployed there), a fourth would take control of the Acre–Safed road and push on to Karmiel, and a fifth would serve as a reserve, awaiting instructions from Tehran

Amsalem describes a decade of erosion in Israel’s response to the communities along the confrontation line, beginning with the decision to remove long guns from the communities. “We were collectively punished,” he recalls. The result was an operational absurdity: under the “surprise infiltration” order, fighters were required to leave their homes and drive to the brigade to sign out weapons. “They explained to us that there was no concrete threat,” he says. Some standby squads disbanded, and on the eve of the war, there were even discussions about cutting the positions of community security coordinators.

Moshe Davidovich, chairman of the Forum of Confrontation Line Communities and head of the Mateh Asher Regional Council, says that “while in the south at least the residents in the standby squads had weapons waiting in an armory, here, facing a certain threat, there was nothing.” The promise of a rapid IDF response collapsed in the moment of truth: “It took the army about 24 hours to arrive, an eternity in terms of an invasion.”

As noted, the army relied on intelligence to provide timely warning, and on the assumption that while the forces deployed along the border, with the assistance of standby squads and units such as Shayetet Dvora, would block the infiltration, additional forces would be rushed north. Lt. Col. (res.) Sarit Zehavi, founder and president of the Alma Center for the Study of Security Challenges in the North, who served for about 15 years in Military Intelligence, first in the Research and Analysis Division and later in Northern Command, argues that the notion Israel could have stopped such an invasion this way is an illusion. “I argue forcefully with the claim that we would have known how to stop an attack like this,” she says. In her view, the system fell victim to a psychological trap of “normalization.”

What does that mean?

“Imagine a terrorist organization plants an explosive on a route the IDF uses. For three months the explosive is there, and the terrorist doesn’t detonate it. The soldiers get used to the landscape, the commanders get used to the quiet. But can anyone say when he will decide to press the button? That is exactly what happened on the northern border. The presence of Hezbollah operatives on the fence was normalized, and therefore the claim that we could have known in real time is simply irresponsible.”

What caused this?

“The system was captive to the conception that Hezbollah was deterred and focused on reconstruction, just as they thought around the gas agreement. When the assessment reaching the chief of staff is ‘the enemy is not interested in attacking,’ no sign on the ground will change the picture.”

Sarit Zehavi Photo: Rami Zarnegar

Sarit Zehavi Photo: Rami ZarnegarZehavi, who served in Northern Command until 2013, points to the breaking point at which the army stopped preparing and began gambling. “During my service, the IDF prepared unequivocally for a scenario of a massive infiltration and fighting inside Israeli territory. Everyone knew Radwan’s plan to invade the Galilee. The big question that must be asked is what happened in the decade between 2013 and 2023. How did it happen that in 2013 we prepared for a war for our homes, and in 2023 the communities stood completely empty of soldiers, totally exposed to the whims of Nasrallah?”

In June 2025, in an interview marking the end of his tenure as commander of the regional brigade in the eastern sector of the Lebanese border, Col. Avi Marciano, commander of Brigade 769, candidly acknowledged the “luck” on our side, the ability to strike and erase the threat of conquest over the north. “I don’t want to make excuses for ourselves. There is an insane achievement here, but also a lot of luck. Some will say there was divine involvement. The cards were played in our favor,” Marciano said. “We took a very, very hard and painful blow in the south, on one side of the ribs, and because of that we saved the other side. That’s what happened. It could just as easily have happened the other way around, with the attack opening from here and the south going on the defensive.”

Marciano entered his post as commander of the brigade along the Lebanese border about a month and a half before the outbreak of the attack in the south, but before that he served in Northern Command and cannot say he was unaware of the scale of the threat. “To tell you that we were fine as an army beforehand? Absolutely not. I’m ashamed of it. Any officer who isn’t ashamed of this, in my view, missed something at Bahad 1 along the way.”

Chapter 5: The lesson

After October 7, the Israeli military launched about 40 internal investigations into various aspects of the war. Some addressed the northern front, but no comprehensive public report was released. Eighty thousand displaced northern residents remain deeply unsettled. Asked about this, the military said all failures described were thoroughly investigated and corrected, even if no single consolidated report exists. According to the military, forces along the northern border have more than doubled, a new brigade has been added, Israeli troops now operate forward positions inside Lebanon, civilian defense squads have been expanded and rearmed, and engagement policies have changed.

Still, many residents feel lessons were learned behind closed doors. An investigation, they argue, is not just about tactics but about restoring trust.

So why did Nasrallah not invade?

Several explanations exist: ego, loss of surprise, fear of escalation or, most likely, a decision in Tehran. “Iran needed time and calm to advance its interests with the United States,” said Shapira. “They did not give Nasrallah the order to go all in.” When Israel later struck Iran directly, Hezbollah was already battered, and Nasrallah, killed months earlier, never saw his vision collapse.

Israeli military response

In a statement, the Israeli military said its pre-October 7 policy along the Lebanese border was professionally reviewed and fundamentally transformed. “The military failed on October 7,” the statement said. “Out of that failure, deep changes were implemented. Today we operate proactively to eliminate enemy capabilities as they emerge.”

The military said Hezbollah was severely damaged during the war, with thousands of terrorists killed and major capabilities destroyed, and that enforcement actions continue. Force levels along the northern border have more than doubled, additional defensive infrastructure has been built, civilian defense units expanded and armed, and ongoing dialogue is being held with local leaders. “All claims that ignore the profound changes on the northern border misrepresent reality,” the statement said. For residents who lived for years under the shadow of catastrophe narrowly avoided, the question remains whether those lessons will endure.

First published: 05:02, 01.18.26