They know each other very well from their joint operations in Gaza, the West Bank and Lebanon. But a heart-to-heart conversation is a whole different battlefield for them.

On the eve of Israel’s 77th Independence Day, the commanders of the IDF’s elite commando units — Duvdevan, Egoz and Maglan — open up about everything: how to comfort a soldier who’s lost friends, how they cope with the findings of the October 7 investigation reports, what it feels like to take out a terrorist at point-blank range and what it’s like to become a father between an operation in Jabaliya and the daring Operation Arnon to rescue hostages

As the joint interview draws to a close, the three commanders begin making their departures elegantly. Lt. Col. Z, commander of Maglan, apologizes that a certain situation demands his attention. Lt. Col. S from Egoz hints it's getting late, and Lt. Col. A from Duvdevan casually mentions he’s hungry, showing his phone. An incoming call: his wife is trying to reach him.

That’s roughly when I ask if, on this Independence Day, the people of Israel can hoist the flag with pride, because after all, October 7 still lingers; October 6 haunts us again. The hostages are still in captivity. The Israeli leadership has lost its people. The nation is examining its way forward. So many circumstances have made even raising a flag a nontrivial act. We need someone to remind us we can. Perhaps these three, the commando unit commanders, who’ve seen the price of war from very close, will be able to do so.

“Factually, yes, the people can raise the flag after an attempt to wipe us out a second time,” says the Duvdevan commander. “Make no mistake, Hamas had no intention of stopping their massacre at the Gaza border communities. If Hezbollah had joined in, it would’ve been something else entirely. So yes, we experienced the most traumatic event since Israel's establishment. But the flag can wave with pride in Be’eri, in Kfar Aza, in Nahal Oz. No one is going to rest, no matter the price we pay, and we are paying, so that life can go on and for the flag to be hoisted proudly."

“Not only can we raise it, we must, every day, not just on Independence Day,” the Egoz commander adds. “Not for the fabric, but for what it represents - the people of Israel, our unity, our bond. So, yes, there’s a lot of background noise, but I don’t think that’s the mainstream."

The Maglan commander reacts with some irritation. “There are ten million Jews worldwide, and not a single neighbor who likes us. We’ve lost so many, so many are injured, and maybe we are threatened more than ever. So, after all the insanity, the threats, and pardon the word, all the crap we’ve swallowed, you’re telling me that I cannot wave my flag with pride?"

“This week, I did inspections. The protocol requires hoisting a flag in the center of the unit, but there wasn’t a single room without a flag - I saw it everywhere, on patches, walls, wherever they could put one."

“So yes. From where I stand, absolutely. I’m proud. If I gave up a year and a half of my personal life and did not spend time with my family, it’s only because I believe in that flag. I hope that answers your question."

Espresso and cows

In a freezing air-conditioned office, the three commanders gather. Though they know each other well from the battlefield in Gaza, Lebanon, the West Bank, sitting down for an open heart-to-heart conversation is a rare occasion. They usually have enough fronts on their minds.

It’s the eve of Israel’s 77th Independence Day. This year marks a decade since the founding of the IDF’s Commando Brigade, yet the timing of this meeting is far from celebratory, and not just because a missile alert is expected to be heard soon.

They’ve just wrapped up a day of listening to combat debriefings about Oct. 7 in several communities near the Gaza border. Two of them fought there, yet still learned new details. A., who was with the Paratroopers in Kfar Aza that day, discovered that a Givati force had been fighting the same terrorists nearby. “Totally reasonable for that day,” he notes.

The debriefings, I suggest, are essentially about reliving the failure. “We live that failure every day,” “a punch to the gut,” their voices overlap. “We don’t need to be reminded of it, okay?” A., now Duvdevan’s commander, takes over. “You just get another perspective on a certain area that keeps echoing the lessons we were taught, in every parameter.”

At the time, all three held different roles. A. was a Paratroopers commander. That morning (Oct. 7), he went out for a run in the fields near his home in a kibbutz near Kiryat Shmona (in the north), without his phone. Around 7 a.m., on the way back, he ran into his wife’s parents. “Looks like you need to get to the army,” they told him. At the kibbutz gate, his wife waited for him with his phone.

Then came a frenzied drive to the country’s opposite end, to Sderot, a 1-hour-and-50-minute dash, at speeds reaching 240 km/h, he estimates, while holding his gun outside the window. “The drive on Route 6 was perfect. As I neared the south, passing Beit Kama, the situation unraveled."

By noon, he reached Kfar Aza, where he would remain for the next three days. Fighting. Clearing houses. Evacuating families. Fragmented images running in his head: an armored personnel carrier on a suburban street; a tank bombing a house harboring terrorists; the nighttime rescue of a family.

He describes entering a home; inside, there were a mother, a father, and daughters. The mother looked at him and asked if he wanted coffee.

"That was crazy. A second ago, I was driving past corpses, burned-out cars, terrorists, and exchanges of fire. My whole command post was hit, and three of them were shot in the legs as they entered Kfar Aza. I’d had a brutal, intense day of combat, I was worn out, and then this moment. I said, ‘Yeah, I’d love an espresso’; I saw they had a coffee machine."

"Then I said, ‘Pack it up, we’re leaving.’ The father, who had this strange little silver pistol on the counter, told me, ‘Listen, I’m not going right now.’ The daughters were on their phones, looking at TikTok or whatever. The mother was rolling meatballs. I take a sip from my coffee and say, ‘Look, there's no need to cook, let’s go.’ These were moments when you think, ‘What a surreal day this has been.'"

Z. from Maglan, then a Givati commander, also reached Sderot to fight in that morning. “After two and a half hours, it felt like we were in the wrong place."

An officer, he doesn’t remember who, called, urging him to get to Nahal Oz immediately. “They’re slaughtering the kibbutz. No forces are there. Don’t stop on the way."

“It was unreal,” Z. recalls. “On the way to Nahal Oz, we passed clashes. We saw 15 terrorists there, and Yasam (the Israel Police Special Patrol Unit) officers facing them, conducting a fierce firefight, and I ordered, ‘No one stops, we keep moving'."

As he reached Nahal Oz, there was silence, he recalls. A silence that belied the heavy toll the kibbutz had already paid - in murdered and kidnapped residents- and gave no hint of the 12 hours of fighting and evacuation of 400 people that lay ahead.

“And then, at 6 a.m., I hadn’t slept for who knows how long, and was already seeing double, the kibbutz chairman comes to me and says, ‘I know it sounds crazy, and I know you’re still clearing the kibbutz, but you must milk the cows, or they’ll die.’"

“I had a deputy company commander who grew up on a kibbutz and was a cow keeper. I told him, ‘Take a few soldiers and do it.’ For three days, my troops milked cows in Nahal Oz. The smell of the barn mixed with the smell of corpses."

S. from Egoz, then a Golani commander, had just stayed the weekend with his troops in a different sector. When the attack (of Oct. 7) began, he prepared for escalation in his own area. He remembers the uncertainty. Golani commanders who were fighting in the south weren’t answering. When reservists came to replace him, he headed south with his troops. What was left to do, he says, was mostly handling the aftermath - evacuating the wounded, the dead, and weapons. He will never forget the faces of the soldiers he encountered.

“Their faces were different. Haunted,” he says, running a hand across his own to demonstrate how it looked like. “You realize something hit the guy in front of you that he can’t even put into words. Some, you’d turn to leave, and they’d ask, ‘Don’t go'."

Then came the Gaza maneuver. Then Lebanon. Tactical successes. Tunnels. Casualties. They still haven’t had time to visit all the bereaved families. And amid all this, they assumed command of the commando units.

From Saluki to Balata

I ask the three commanders to share a meaningful battle they experienced through a photo of their choosing.

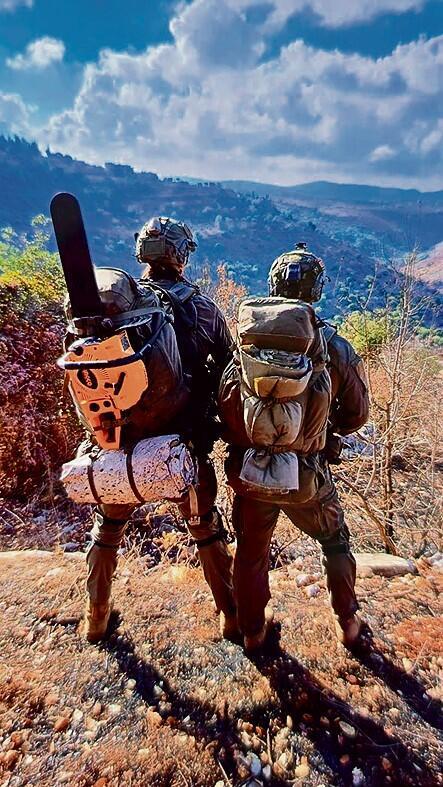

The Maglan commander goes first. His photo shows two reservists on a hill, facing the mountains. A magical blend of clouds and sky bathes the scene in blue.

They’re heading toward the Wadi Saluki in south Lebanon - a tangled, fortified area where they would fight for four days alongside fellow soldiers, striking at a region that had long been a source of rocket fire into Israel.

During the war, Duvdevan, Maglan and Egoz units operated across every front: Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and the West Bank. Here, for the first time, they fought together.

Each of the two soldiers in the photo is weighed down by 70 kilos of equipment, such as camouflage kits. One carries an electric saw to cut through the dense terrain. “No one told him to bring it,” Z. notes.

Soon, on a foggy night, the two will lead a force into a kill zone. Four terrorists will be watching, ready to strike.

“The terrorists were sure they could kill us,” Z. recounts. “They didn’t realize we were watching them. Within 16 minutes of contact, using a special technique, we killed them one by one. I’ve been in many encounters over the past 18 months, but here I got so close, he didn’t even know where I was. When I say close, I mean one-meter close. I’d say 'I was looking him in the eye,’ but it was dark, so I'd say I was close enough to see the flash of his Kalashnikov."

What’s it like to kill someone at point-blank range? I ask. He pauses. “You see the soul leave the body. But he’s in the same situation as you, wishing to do the same to you."

S., the Egoz commander, also shares a photo from Lebanon. It shows a house in the town of Khiam, with a balcony overlooking Mount Dov and an entire surveillance setup.

In his previous role in Golani, S. recalls sitting on Mount Dov as Hezbollah shelled him with mortars and anti-tank missiles. And now, from the house they had taken deep in Lebanon, they were watching that same mountain from Hezbollah's perspective. "You think, wow, we conducted a crucial battle. That was a real moment of closure."

8 View gallery

The house in Khiam, Lebanon where Egoz soldiers found an observation post system facing Mount Dov

(Photo: IDF)

Then it’s Duvdevan’s commander’s turn. His photo shows 12 unit commanders gathered in a Lebanese home overlooking the Wadi Saluki, seated on ornate chairs with drapes behind them. “An Airbnb we rented for the week,” he laughs.

Duvdevan is traditionally focused on the West Bank, but over the past 18 months, it has found itself in unfamiliar arenas, from Gaza operations to its first combat in Lebanon. "This is a unit of skilled people,” A. calls it, describing a battle in Saluki.

“Most of the time, we fought at night, hidden. Then we flipped the script and fought in daylight, exposed. We did it in an interesting way that made the enemy see us, but in doing so, the enemy revealed themselves. Through that deception, we were able to take out four to six enemy squads quickly, with help from the air force."

I ask about other operations, undercover raids. A. describes a daytime mission in the Balata refugee camp to take out a terrorist preparing an attack. Disguised as local youth, Duvdevan fighters entered the area using local transportation.

“Every location has its own characteristics. Jericho is different from Balata, which is different from Jenin. You wouldn’t drive a Ferrari into a kibbutz, though maybe in Tel Aviv it’d make sense. So we use local vehicles to blend in,” he explains.

As the Duvdevan fighters closed in, gunfire erupted. Four were wounded, two seriously. One was hit in the clavicle, damaging an artery. A chase ensued. It was intense.

“In units like ours, the drama is controlled,” A. says coolly. “These are fighters who deal with contact every day. No one is surprised by gunfire or injuries. For the record, all four returned to operational duty."

Thickets, fog and radio call

What a harrowing start to the year. On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, six Egoz soldiers were killed and 30 were wounded in a fierce battle in Odaisseh, Lebanon. A pall of grief hung over the country.

“It was a battle that set the tone, both for us and for Hezbollah,” says S., the Egoz commander. "The price was steep, but the enemy understood we weren’t playing around. We slammed into them. Thirty-seven terrorists killed, by count."

S. began the Gaza maneuver, still as a Golani commander, with a personal setback: during a firefight in the village of Juhor ad-Dik, known to troops as “Chicken Tunnel”, a soldier accidentally discharged a machine gun bullet into S.’s leg. It sidelined him for a month. “It was so frustrating, I thought, better it had hit me in the head and ended it.”

Then, his first operation as Egoz commander would be a grim one: retrieving the bodies of five hostages from a tunnel in Khan Younis. From there, the unit moved north for covert raids, preparing for the potential ground maneuver in Lebanon. “We went two and a half kilometers into a village and found a freshly-dug tunnel, the drill was still hot."

Two of those raids were in Odaisseh, now familiar territory. But nothing prepared them for what erupted there on New Year's Eve.

S. leans forward as he speaks, gripping an imaginary weapon. His eyes shine.

It was a freezing night. Fog. Complex terrain, thicket alongside build-up area. Then we were told on the radio about a clash in one of the houses. He remembers sprinting to the scene amid gunfire. Mortars. Anti-tank missiles. He called in for reinforcements nonstop.

There were wounded, some trapped inside the building. Rescue efforts have been made, and fears of kidnappings have been raised. They were evacuating the injured down a slope, while grenades flew their way. Long, hard fighting was taking place alongside acts of heroism.

S. remembers Capt. Harel Ettinger, a commander in the Egoz unit who insisted on blocking the terrorists’ escape. “I’m going,” Ettinger said. “Wait,” S. told him, "We'll guide a chopper in.” But bad weather made air support impossible.

“He looked me in the eye and said, ‘I’m going,’” S. continues. “I told him, ‘Hold on a second.’ But I realized there was no choice. Ettinger and I went out flanked by his team. We entered the heart of the kasbah. We realized this was where we had to stop the terrorists. Then Ettinger was hit. I remember how we lifted him out. A terrible loss, but the values in that battle were at the highest level."

“Then dawn breaks. It’s twilight, it starts to rain, and you think, ‘God, what more are you going to throw at us?'"

How do you cope? I ask. “When you’re in commander mode, you filter. You don’t let things in. You don’t think about your wife, your kids. You can’t, or you’ll have a personal weak spot. That’s not acceptable in combat leadership."

So, when do you let it in? I insist. “There’s a time for peace, a time for war, and a time to process,” S. replies. Then he pauses, looks at his comrades and says, “Correct me if I’m wrong." They don’t.

Solitude and an embrace

Over the past year and a half, their passports have been stamped not only by every neighboring country Israel has but also a spectrum of emotions: pain, pride, satisfaction, longing, perhaps guilt, and certainly loneliness.

“You’re alone, alone, alone,” says Z., the Maglan commander. “At some point, you realize it’s all on you. When a company commander stands before you having lost 15 soldiers, he’s looking to see if you can support him and show him the best way to act."

They sit silently, arms folded. They listen. There’s a wordless understanding between them, forged by their experiences and the heavy price they paid. Such understanding goes beyond the battlefield.

“Once, if you’d sat us together, I don’t think we could’ve even listened to each other,” Z. says.

They recall their wartime conversations. Jokes. Consults at moments of crisis, such as after the deadly battle in Odaisseh, when S. the Egoz commander, lost six soldiers, and Z., the Maglan commander, called him. They spoke for over two hours.

“Even before he said a word, I knew where he was mentally,” Z. says. “I told him, ‘I’ve got a buck and a half of advice. Listen to what’s coming next for your unit. This is what a crisis means.'"

S.: “He said, ‘I remember how I experienced my commanders in Gaza, who was there for me.’”

Z.: “Basically, I told him he should talk about it. Say the truth, however hard. Not just to the bereaved families. Stand in front of your commanders, understand the mistakes. And it’s hard. It’s hard when people are killed. It’s hard to say, ‘I made a bad call.’ I advised him: 'Start with your own mistakes. And most importantly, don’t let up, no matter what.”

A., the Duvdevan commander: “Before Oct. 7, if you had a messed-up incident, you could call a battalion commander from the ’73 war, say, ‘I read a post-command course paper, stating that you had a crisis in your unit, tell me about it.’ But these days are over. This is a different generation. They’ve experienced 400 times more than any IDF commander, maybe apart from the 1948 generation. And there are things you can’t discuss with your wife or your parents. Only with another commander who’s been through the same experience."

More than a year ago, in his previous Givati post, Z. lost his entire chain of command - four company commanders, a deputy battalion commander, their replacements. So, how do you tell a soldier who’s lost friends that he has to keep going? I ask.

“First, I try to get them back out on missions to restore confidence. Because when you get hit, you feel like a personal failure, even if it wasn’t your mistake. Like falling off a bike, you don’t want to ride again. So you have to get that soldier or commander to a place where he regains trust in himself. And then you give a hug. Show you’re support of him."

And what happens in that hug?

“Each one is different. Sometimes you look him in the eye and say, ‘You did what you could, that’s life.’ Sometimes, it’s a dark, cynical joke."

And who hugs the commander who lost four company leaders? I ask.

“Sometimes a hug from a soldier is enough. He doesn’t have to be the chief of staff to give a hug."

He remembers a bloody battle in Khan Younis. Two soldiers were killed. Nine were wounded, including a company commander.

“I found myself pulling people out", he describes. "The next day, some soldiers asked to speak with me in private. They said it was personal. Then in the room, one started crying, saying, ‘I just wanted to say thank you. If it wasn't for you, we wouldn’t have made it alive.'"

“So I decided to go to the company and tell them what happened. In that battle, I tried three times to storm a room with two terrorists. Twice, I got blown back by grenades. Then, at one point, with everyone else tending to the wounded or killed, I realized I was alone. I was about to go into the room and knew I wasn’t coming out alive. That it was over for me.

“Then I felt a tap on my right shoulder. A soldier stood there, saying, ‘Commander, I’m with you.’ It was surreal, it had never happened to me before. I looked at him, couldn’t even speak, and suddenly I had confidence. I knew we were going to win that room. And we did. We went in and killed the terrorists.

“So I decided to gather the unit and tell the story, explaining: ‘I don’t know if I could’ve gone in there without him. You wanted to thank me, but I want to thank you.’”

Some redness in the eyes

I ask when they last cried. The Duvdevan commander, a father of two, is the only one who remembers. It was exactly a year ago when his wife gave birth. “Let’s not exaggerate,” he smiles. “Call it a little redness in the eyes.”

Recently, he and his wife went through old photos and realized there were none from her latest pregnancy. No one was around to take pictures. Still, he made it to the delivery. He had just come from fierce fighting in Jabaliya, then participated in Operation Arnon to rescue the hostages, and had four days in between for another mission.

“I told my wife, ‘You've got four days,’” he says, raising four fingers. “‘Let’s go up to Ziv Medical Center. Get induced. It’s your call, but I think it’ll work. I may not be a certified doctor, but I’ve been trained by war.’ She gave birth in the morning.”

Life is born amid war and loss, I note. “I came straight from a horrific battle in Jabaliya. I lost six soldiers there. I had some really rough days with myself. But on the other hand, life teaches you to swallow hard, learn your lessons, and move forward. There's no other option. You can’t stop. You’re responsible for so many people. You can’t wallow, you can’t start twisting with thoughts. Some psychologists will say we’re messed up, that’s fine. I think we’ve seen life from angles most never will. And we know the difference between good and bad. And even here, a child was born. You give a kiss, make a cut, and you're back to Operation Arnon.”

Then he smiles. “I won’t lie,” he adds. “You leave a newborn and come back to a fully 'baked' baby. There’s something really positive about that."

“When I went to war, my son was in kindergarten,” says Z. from Maglan. “When I came back, he could read, write, and he finished first grade.”

The Maglan commander has three boys. The youngest, now a year and a half, was born just before the war. With missions that take him away for four months at a time, he hasn’t seen much of his growth. “But I still have a strong connection with him. I savor every moment.”

He recalls a rare day off when he picked up his toddler from daycare. “The neighbors looked at me and said, ‘That’s not your kid’s daycare.'"

Right now, his wife is heavily pregnant. A fourth son is on the way. He’ll never forget how he found out. He was in the middle of a battle in Khiam, Lebanon, when a message came through the secure line: your wife’s trying to reach you. “I thought the car broke down or something. It took me hours to process.”

“And when you get home,” adds S., father to a 3 and a half-year-old, “you can’t say a word. Like if the kid’s watching TV, and I would say, ‘Since when do we have TV time at home?’ And my wife would answer, ‘Don’t butt in. Be here every morning, then we’ll talk.’”

You’re describing these things with a smile, I say, but you're missing whole pieces of life. “There are also hostages,” the Duvdevan commander replies. “And I think that if I do the right things, I might, with one move, help bring them back. And I’ve got a battalion I want to speak to before the next operation. I have two kids, but 700 soldiers, and at this point in my life, I’m responsible for them. So personal life goes on hold. Did any of us sit on the beach with a beer and chill? That's not happening.”

“Hasn’t happened for me in a year and a half,” says the Maglan commander, doubled by the Egoz commander.

The spirit of the fighters

Now it’s time to wrap it up. First, a few questions about issues on the agenda, such as, "Can the IDF still be considered the most moral army in the world?

“When mistakes happen, and they do, we stop, we investigate, we ask hard questions and take disciplinary action, when necessary,” says A.

And can military action alone bring all the hostages home? “The answer is no,” says S.

And finally, I say, "There is a chance that one of you might end up on the IDF General Staff someday, maybe even as the future chief of staff. What kind of generals would you be?

The Duvdevan commander answers first: “We’d understand that we live in a neighborhood where nothing can be taken for granted, and that our enemy is so ideologically driven that we can never think they’ll stop wanting to destroy us. We must never forget the basics: training, techniques, discipline, order, but most of all, listening to the troops on the ground."

His two fellow commanders agree. “There’s so much knowledge and wisdom at the lower levels,” says the Egoz commander. “In the end, it’s the spirit and professionalism of the people that win wars."

The Maglan commander adds: “Maybe like the Yom Kippur War generation, today’s battalion commanders don’t trust anyone, in a good way. I’ve learned that intelligence assessments are important, but you have to constantly imagine the thing no one thinks can happen. And not just imagine it, but prepare for it. That’s the scar Oct. 7 left us with.

“Besides, you’ll always want more weapons, more training. But in the end, it’s about the outcome. It doesn't matter what you had or didn’t have. I’ve fought battles with 10 tanks, and I’ve fought without any. You have to win with what you’ve got. No excuses.”