Last month, after who knows how many reserve duty call-ups and hundreds of days in uniform, Dudi, the husband of Merav Geva-Grumer, finally came home. No more parent-teacher meetings and kindergarten parties without a father. No more jolts of fear at every knock on the neighbors’ door. On the face of it, this was the happy ending. From now on, it is a calm, harmonious routine and life ever after.

But the truth is that the story is far from over. In some ways, it is only the beginning.

It sounds paradoxical, but the days without Dudi were somehow easier for her, at least at first. “Everyone was very mobilized, supportive and helpful,” Geva-Grumer says. “But now, when that period is supposedly behind us, I feel like everything is coming up. It feels like we are back to routine, but not really.”

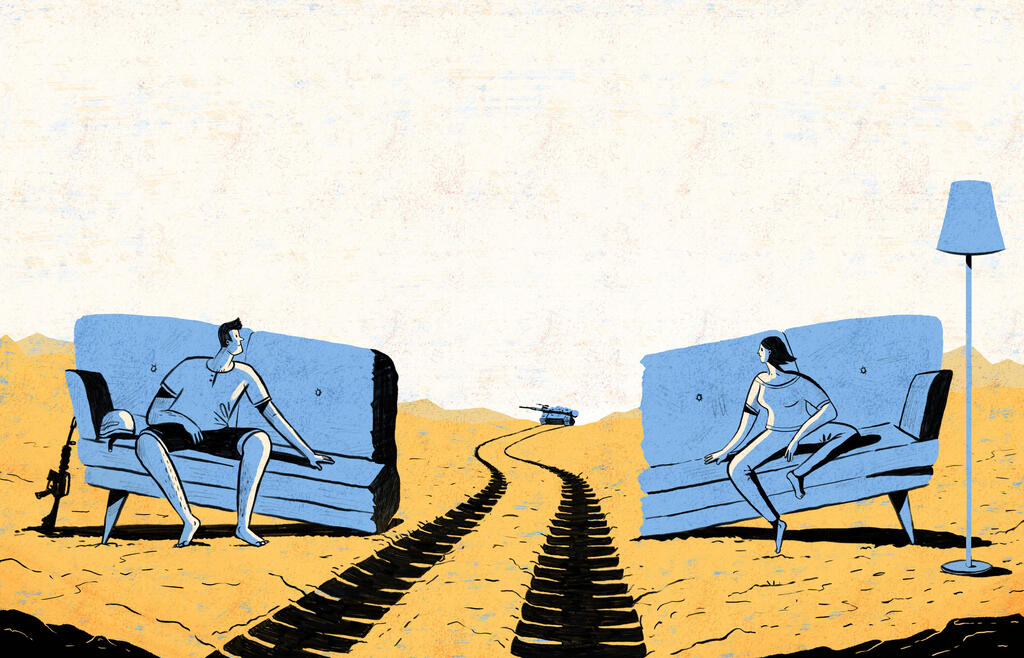

The difficulty of getting back to the couple dynamics they knew before October 7 is felt everywhere. For example, when Dudi, a reserve armored company commander and a VP marketing at a high-tech company in civilian life, tries to readjust to life outside the army, it takes more than switching from khaki to jeans. Even the language and manners need to be 'civilian' again.

“There is a gap between the two worlds,” Geva-Grumer says. “In the army there are missions and targets. You feel very significant. At home it is different. Not everything happens the way you want. It works differently from the military. At home, you cannot give orders.”

Dudi, whose reserve duty was everywhere, fighting in every front, sometimes feels that returning home is a signal that everything is fine. Geva-Grumer, who stayed behind with two young kids and put her life on hold, explains that it is not as simple as that. “No, not everything is fine. I went through things. The kids went through things. You went through things."

Geva-Grumer, an actress and creator, a member of the Ramat Gan City Council and an activist for reservist families’ rights, also speaks about anger and frustration. “It feels like he doesn't fully appreciate my effort. I stopped my life while he was in reserve duty, and it is not always sufficiently acknowledged.”

The expectation that he would return from reserve duty and immediately make up for the lost couple and family time crashes into reality. Old arrangements were shaken, and now a new relationship contract has to be written.

“Before the reserve duty, there were days he came home late and evenings when I was not around,” she says. “During reserve duty, everything was on me. So when he came back, there was an expectation that he would ‘compensate' for that period, that I could also 'breathe'. But he also has to make up for the time he was absent from work, and that creates tension.

Tension, frustration, a shaken old order are words that come up again and again in the conversation with Geva-Grumer, and she hears them repeatedly in conversations with other couples. “I hear about many couples who are facing problems,” she says. That does not surprise her. “We are relatively young people, dealing with something insane. Not everyone can cope with it. Not everyone manages to bridge the gaps."

“‘I told him, take the backpack out of the room, it is staring at me,’ Michal said as she shared how hard it was to get close during one of the leaves. ‘I realized I was afraid to open up to him again, because it was only a matter of time until they took him away again and my heart would break. Only after he came home did I understand that since he was drafted, I had switched into anger mode. I think it helped me close my heart and not go crazy from worry and longing. And now that he is here and I want to open my heart again, I cannot. And when my heart is closed, my body does not want to either.’”

Only years from now, if ever, will we fully understand what hundreds of days of reserve duty, round after round, do to the family unit. What does a home look like when one of its pillars disappears and returns, disappears again and returns again? Perhaps years from now we will be able to sum up divorce rates, the scale of post-trauma, the number of people who will never be who they were before.

Each couple is still far from reaching its own conclusions. For now, it is only possible to begin sketching the contours of this crisis, hidden in the space between the bedroom and the kitchen. Like an injured body, like a soul exposed to unbearable sights, like a collapsed business, the relationships of reservists and their partners also need rehabilitation.

The book ‘You're Suddenly Back’ (Sela Meir Publishing) tries to offer some answers, and above all to send a message to the hundreds of thousands of couples now trying to return to a cautious postwar routine. If you feel anger or resentment, if your sex life is faltering, if it is hard to function again as a two-parent family instead of a single mother and a father who occasionally calls to say good night, you are not alone. And you are very, very normal.

The book was written by Smadar Miller Levi and Shay Urim. He lives in Peduel in Samaria. She lives in Kiryat Tivon. He is a clinical social worker, sex therapist and reserve mental health officer who still moves between his private clinic and the military brigade he accompanies in service. She is a teacher of mindful sexuality and healthy relationships who runs, together with her partner, a school for couples.

The literary pairing, initiated by the publisher, can be seen as a bridge across Israel’s social divides. But conversations with the two reveal that when it comes to relationships, there are no disagreements. This crisis is unlike anything they have known, even after more than a decade of guiding and treating couples.

“The book includes the voices we heard in the clinic, in meetings, in the mental health officer’s room,” Miller Levi says. “I thought I'd seen everything in the field of relationships, truly everything. But here something else is happening, something we are not familiar with and do not fully understand. The relationship system was shaken not once, but again and again, in every round of reserve duty. This is a different event.”

"It's not that couples in the past did not have to cope with prolonged absences or temporary separations. But these rounds of reserve duty are something entirely different, because of the life-threatening danger, the ongoing anxiety and the call-ups that seem to have no end. “Taken together, these factors make the situation unprecedented,” she adds.

Urim, who served as a reserve mental health officer at the start of the war and now serves in a regular battalion, knows the cost of war very closely. Two of his five children were wounded during the war, one of them still in rehabilitation. Alongside that, he has been exposed up close to the relational price paid by reservists.

What happens inside the family unit worries reservists no less, and sometimes more, than issues related to the fighting itself. “It was very clear and present,” he says, and Miller Levi agrees. “In our culture, even if we argue like hell on the way to a family meal, we end up smiling when entering the room. No one talks about what is happening inside the relationship, so there is no way to know that the same crisis is happening for others."

“When Yohai came back after a month of reserve duty, they simply could not reconnect. ‘We felt like two hedgehogs trying to hug,’ Hadas said. ‘It was frightening. Maybe our magic was broken?"

We do talk about the difficulties faced by reservists, the heavy burden, the price paid by children, the problems with workplaces and collapsing businesses. But somehow, at least in the common public image, once the round ends and the partner comes home, the difficulties end as well.

Reality, however, is not a bank commercial. In real life, the closing scene of the embrace is sometimes only the opening moment. “In reality, that hug is not always just joy,” Miller Levi says. “And then cycles of shame and guilt begin, of ‘what is wrong with us.’ Another layer of worry comes up.”

The book’s first goal, they say, is to dispel loneliness. To normalize. So that couples now dealing with the consequences of the war and with the open wound in the middle of their living room know they are not alone. “As with many things related to the soul, people often feel alone, as if they are the only ones dealing with this kind of difficulty.”

“It took us a long time to get used to the fact that Dad was not around, but eventually we managed. And now, when he comes back, the order is disrupted again. And just as we get used to him being here, he is being drafted again. It's exhausting.” Urim and Miller Levi hear these sentences all the time. Sometimes, behind closed clinic doors, there are even harsher ones.

“There were women who said, 'I am waiting for him to go back to Gaza',” Miller Levi says. “A family is a bit like a soccer team. Everyone has a role. There is a striker and a linesman. One child cracks jokes, another always causes trouble. We take on roles. But what happens to the team when the striker suddenly disappears?”

The answer is that the team keeps playing. The family continues to function as a family. But the roles are reorganized. “We settled differently. We already have a routine without you. Now you're back and disrupted our new order.”

That new order does not always match the wishes of the woman who stayed behind. “I am not the mother I want to be,” one woman testified in the book. Instead of raising the children together, as she and her husband had dreamed, she raised them alone for long stretches, under relentless pressure.

“I just need him to come back and say, ‘Wow, you did an amazing job,’” another woman shared. “I know it wasn't perfect, but I need his validation that everything is OK, that the house is OK, that the kids are OK.”

“I felt my hands were rough, and I was afraid I would scratch her when I touched her. For a month and a half I was operating heavy, dusty equipment. Everything had to be strong, forceful, with a slam. Suddenly, I felt like I had forgotten how to be gentle. It was the first time in my life that I couldn't function. I could not believe it was happening to me. And while I was in shock at myself, I was also thinking about how long she had waited for this and how badly I wanted to make her happy. I felt like a rookie. Like nothing. I wanted to disappear."

When it comes to sex, the gap between expectation and reality can be especially painful. “Something about his touch feels strange, rough and unpleasant. My body does not recognize him,” one woman quoted in the book says.

These stories repeat themselves. One example is the story of Sarit and Yoav. Yoav returned from prolonged service in Gaza. When he walks through the door, the longed-for hug arrives, Sarit relaxes and feels her body begin to release the stress accumulated over weeks of waiting. She feels calm and believes the evening will unfold exactly as she imagined. But after a few minutes, something changes. She feels Yoav restless, moving uncomfortably, eager, reaching for touch as he did throughout the weeks in Gaza. This time, she is the one in the space, not the enemy. He speaks little. He asks about her, but she knows him, senses the rhythm and understands he has no patience for conversation. In an instant, her sweet anticipation turns into unease and a sense of estrangement.

“For most couples we met, both partners automatically assumed that the accumulated sexual hunger would produce a unique reunion,” the authors write. “Some imagined it passionate and wild. Others dreamed it would be emotional to tears, closer and more intimate than ever. Almost everyone expected something different from their usual sex life, something better, unforgettable. But distance does not always work in favor of physical intimacy. “When couples spend a long time communicating only digitally, without their bodies in the same space, it has an effect,” Miller Levi says. “Sometimes it is subtle, but it is significant and affects the ability to understand one another.”

When physical distance finally closes and the moment of embrace arrives, a sense of estrangement can appear. The mind says, 'This is my beloved, but the body signals, 'Wait, who is this? Why is he so close?'. When that happens, the transition to sexual touch can falter. For one partner it may be obvious, for the other it may be, 'wait, I need emotional closeness before physical closeness'. Around that moment, tension, feelings of rejection, hurt and appeasement can accumulate.

And that is before speaking on the collective trauma, the horrifying videos, the stories from captivity. These, too, can seep into relationships and sexuality. “We are making love and suddenly I remember something I saw in a horrific video,” Miller Levi explains. “In the end, we are creatures that respond to danger, fear and distance.”

The book does not offer magic solutions, but first and foremost recognition. “We went through something enormous, and it affects and seeps in,” she says. “It's normal. Sometimes you need help and guidance. It is an invitation to breathe, not to panic about the fact that we are affected by what we went through.”

So what can be done? “Enlist optimism, compassion and understanding,” Miller Levi says. “Have some patience until things settle."

Her most important message is that the crisis is not only normal but almost inevitable. “If your relationship does not go through a crisis now, that would be the abnormal thing,” she says. “You went through an unreasonable event, with so many pressure points, over such a long period. The relationship was challenged on so many layers. If you are experiencing chaos now, it is not you. It is not your fault, and it does not mean there is no love between you."

"What you are going through now is not only the result of your personal story, but of an unreasonable and prolonged strain on your relationship.”

And perhaps something sweet can emerge from the bitter. “A lot was shaken by the war, and there is an opportunity to shake up the relationship too. A relationship is a living thing that needs to develop. There is an opportunity here to do that. People often come to couples therapy after a crisis. Now there is a chance to use the crisis before it's too late.”