In a cemetery outside Kingston, Jamaica, several weathered tombstones stand apart. Their inscriptions are in Hebrew. Carved above some of the lettering is an unexpected emblem: a skull and crossbones.

The graves belong to some of the earliest European settlers of Jamaica — Spanish and Portuguese Jews who fled persecution in Iberia and rebuilt their lives at the edge of empire. In the upheavals of the 16th and 17th centuries, some of those exiles became merchants, diplomats and, in certain cases, privateers operating in the violent maritime conflicts of the Mediterranean and Atlantic worlds. Their story begins in 1492.

3 View gallery

Capture of the Pirate, Blackbeard, 1718 depicting the battle between Blackbeard the Pirate and Lieutenant Maynard in Ocracoke Bay

(By Jean Leon Gerome Ferris)

In March of that year, Spain’s Catholic monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, issued the Alhambra Decree ordering all Jews in their realms to convert to Christianity or leave within four months. The edict came as the monarchs consolidated political control after completing the Reconquista with the conquest of Granada, the last Muslim-ruled kingdom in Iberia.

For centuries, Jewish communities had lived in Iberia, some tracing their presence to Roman times. By the late Middle Ages, however, anti-Jewish violence had intensified. In 1391, widespread massacres and forced baptisms dramatically reduced Spain’s openly Jewish population and created a large class of conversos — Jews who converted to Christianity, voluntarily or under duress.

Many conversos integrated into Christian society. Others were suspected of secretly maintaining Jewish practices, becoming targets of suspicion. In 1478, Ferdinand and Isabella established the Spanish Inquisition to investigate heresy among New Christians. The institution evolved into a permanent bureaucracy that relied on denunciations, secret testimony and, in some cases, torture. Convicted individuals could face imprisonment, confiscation of property or public execution in ceremonies known as autos-da-fé.

By 1492, religious conformity had become central to the crown’s vision of political unity. Jews who chose exile were required to sell property quickly and were barred from exporting gold, silver or arms, often forcing them to accept goods or promissory notes of uncertain value. Many lost their wealth in the process. Families crowded the roads to port cities, uncertain of where they would land.

That same year, Christopher Columbus departed on his first voyage across the Atlantic. His expedition left just days after the expulsion deadline. The twin events — expulsion and exploration — would soon become intertwined in ways few could have anticipated.

The expelled Jews, later known as Sephardim from the Hebrew word for Spain, scattered across the Mediterranean and beyond. Many found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, whose rulers welcomed skilled migrants. Others settled in North Africa — in cities such as Fez, Tunis and Algiers — where established Jewish communities already existed. Some eventually reached the Netherlands, where the Dutch Republic’s emerging policy of religious tolerance created new opportunities.

A significant number of Sephardic Jews had experience in maritime trade. They were merchants, navigators and cartographers, fluent in multiple languages and familiar with Iberian ports and shipping routes. In their new homes, these skills became valuable assets.

In North Africa, corsairing — state-sanctioned maritime raiding — was already embedded in regional politics. Muslim rulers and Ottoman authorities issued commissions to private captains to attack enemy shipping, particularly Spanish and Portuguese vessels. Some Sephardic Jews participated directly in this world, while others financed voyages, brokered goods or provided intelligence.

One of the earliest figures associated with Jewish involvement in Mediterranean privateering was Sinan Reis, described in European correspondence as “Sinan the Jew.” Though details of his origins remain debated, he is widely believed to have come from a family expelled from Iberia and to have risen within Ottoman naval ranks.

By the early 16th century, the Ottoman Empire and Habsburg Spain were locked in a prolonged struggle for dominance in the Mediterranean. The famed corsair Hayreddin Barbarossa entered Ottoman service and was appointed grand admiral by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. Sinan served as one of his close lieutenants.

In 1534, Ottoman forces seized Tunis, seeking to establish a strategic base in North Africa. Spanish forces under Charles V retook the city the following year in a massive expedition. In 1538, at the Battle of Preveza, Barbarossa’s fleet decisively defeated a Holy League navy assembled by the pope and Spain’s allies, cementing Ottoman naval dominance in the eastern Mediterranean for decades.

The corsair world was brutal. Both Christian and Muslim fleets relied heavily on enslaved oarsmen. Raids devastated coastal communities from Italy to Spain and North Africa. While some Jewish exiles saw participation as a form of retaliation against former persecutors or simply as economic opportunity, they operated within a system marked by violence and coercion.

By the early 17th century, attention shifted northward to the Dutch Republic, which had broken from Spanish rule and was fighting a global conflict against Iberian power.

Samuel Pallache, born in Fez around 1550 to a Sephardic family expelled from Spain, became one of the era’s most complex figures. Educated in Jewish law and active in trade, Pallache entered the service of the Moroccan sultan as a diplomat and intermediary.

In 1610, he helped negotiate a treaty of friendship and commerce between Morocco and the Dutch Republic — among the first formal agreements between a North African Muslim state and a European power. Under Moroccan commission, he also engaged in privateering against Spanish vessels.

In 1614, after capturing Spanish ships, Pallache docked in England and was arrested following pressure from the Spanish ambassador, who demanded his execution as a pirate. Dutch officials intervened, asserting that Pallache was a licensed privateer acting on behalf of a sovereign ally. English authorities ultimately released him, treating him as a diplomatic figure rather than a criminal.

Pallache died in 1616 in Amsterdam, where Prince Maurice of Nassau and members of the Jewish community attended his funeral. His life spanned Morocco, Spain, the Netherlands and England — reflecting the fluid loyalties and shifting alliances of the age.

Across the Atlantic, Sephardic Jews and conversos also played roles in the expanding colonial world. Despite Spanish purity-of-blood laws barring Jews and their descendants from settling in the New World, some reached colonies in Mexico, Peru and Brazil through forged documents or by concealing their ancestry. The Inquisition followed them overseas, conducting trials in Mexico City, Lima and beyond.

In Amsterdam, a new generation of Sephardic Jews aligned with Dutch commercial and military ventures. Among them was Moses Cohen Henriquez, whose family had fled Iberian persecution and rebuilt their lives in the Netherlands.

In 1628, Dutch forces captured part of the Spanish treasure fleet in the Bay of Matanzas, Cuba — one of the most lucrative maritime seizures in history. Henriquez is believed to have contributed intelligence that aided the operation. The captured wealth significantly bolstered Dutch war finances.

He later participated in Dutch campaigns in northeastern Brazil, where a period of relative religious tolerance allowed Jews to establish open congregations and synagogues. When Portugal retook Brazil in 1654, some Jewish settlers relocated to New Amsterdam, forming one of North America’s earliest Jewish communities. Others moved to the Caribbean.

Jamaica became a focal point after English forces captured the island from Spain in 1655. Seeking to strengthen the colony and weaken Spanish power, English authorities permitted Jewish settlement. Sephardic merchants, traders and former privateers helped develop Jamaica’s economy, particularly in sugar production and transatlantic trade.

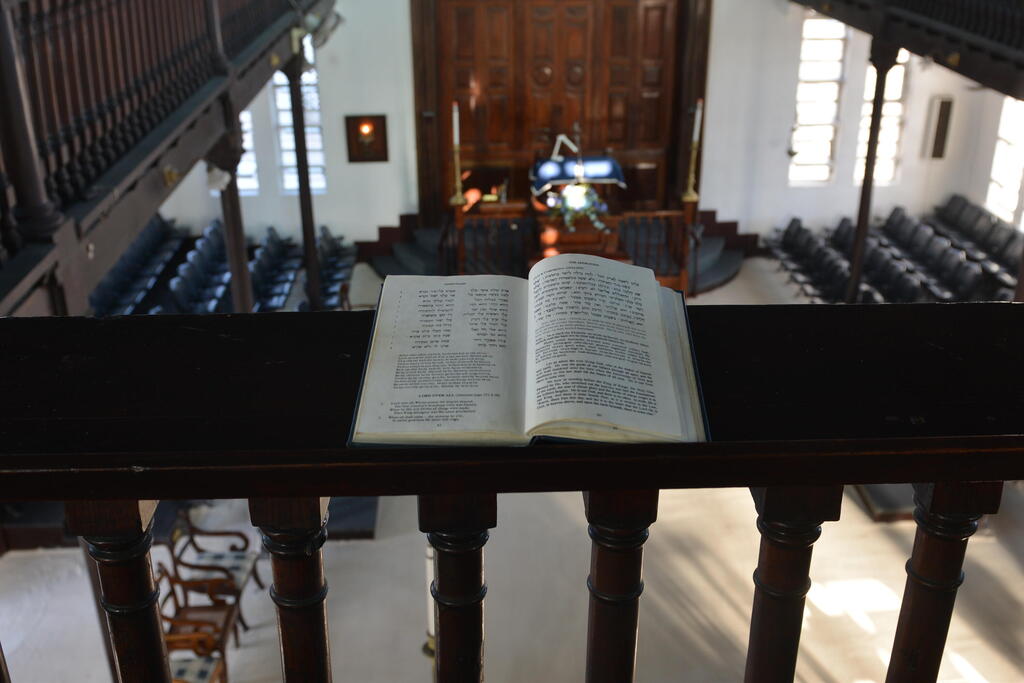

By the late 17th century, Kingston had a visible and prosperous Jewish community. Synagogues were built with sand-covered floors — a Sephardic custom recalling centuries of secret worship under Iberian persecution. Hebrew-inscribed tombstones in Jamaican cemeteries reflect families whose journeys spanned Spain, North Africa, the Netherlands and the Caribbean.

The notion of “Jewish pirates” has often been romanticized, and historians caution that documentation remains uneven. Some figures are clearly attested in naval and diplomatic records; others appear only briefly in hostile European accounts. Not every Sephardic merchant took up arms at sea, and not every corsair labeled “the Jew” in contemporary sources can be firmly identified.

Still, archival records confirm that Sephardic exiles and their descendants were active participants in privateering networks aligned with Ottoman, Moroccan, Dutch and English interests. They appear in treaties, court transcripts, shipping logs and colonial charters.

By the late 1600s, Jewish communities stretched from Amsterdam and London to Recife, New Amsterdam and Kingston, connected by kinship and commerce across oceans shaped by war and empire. Some of those communities traced part of their history not only through synagogues and markets, but through ships, naval battles and captured cargo.

In the cemetery outside Kingston, the Hebrew letters have faded with time. The skull and crossbones carved above them remain.