For more than two years, IDF reserve soldiers have been repeatedly called up, leaving their lives behind, rotation after rotation, despite exhaustion and mounting hardship. Their businesses have been harmed, sometimes collapsing entirely. Their children cry and beg them not to go. Their partners remain behind to hold the household together alone.

The People of the Year for 2025, chosen by ynet and Yedioth Ahronoth, are the reservists. In a special project, they sum up the past year and speak about the heavy price, the trauma and severe injuries, the friends they lost, but also the sense of mission and their hopes for 2026.

‘When my husband finished his sixth rotation, I began mine’

With two small children at home, Private (res.) Hadas Krisi, 28, enlisted as an operations sergeant and along the way became one of the leading figures in the struggle for an equal draft law.

Krisi, head of the Aderet pre-military academy, is married to Rotem and the mother of two children: Ishi, 5 and a half, and Telem, 1 and a half. At 18, she completed national service at a hostel for at-risk girls in Jerusalem and served as a youth counselor in the Bnei Akiva movement.

“On the day my husband finished a rotation, I left for basic training,” Krisi said.

During the war, alongside the hundreds of reserve days completed by her husband, a fighter in Brigade 16, Krisi decided to put on a uniform herself for the first time.

“From the outbreak of the war, I wanted to enlist, and every time my husband was called up for another rotation,” she said.

After giving birth in March 2024 to her youngest daughter, she formally enlisted in June as an operations sergeant in the 188th Brigade.

“On the day my husband finished one rotation, I went to basic training. On the day I returned from training, he left for another rotation. When he returned from his sixth rotation, I began my reserve duty,” she said. “I’m glad I did it. I hope they call me again so I can help.”

Alongside her family’s contribution to the reserve system, Krisi is among the leading figures pushing for an equal draft law on behalf of the Reservists Movement, serving as head of its youth headquarters.

She vividly recalls the first time she visited the Knesset.

“I arrived with youth from the pre-military academy because they decided to draft them in the middle of their year,” she said. “We came to fight to prevent that, to allow them to complete the year so they could enlist as prepared as possible, as they had hoped. The decision changed, and the students will enlist at their designated time and serve in the significant roles they were assigned.”

Since then, Krisi has frequently attended committee hearings, giving voice to those who serve and their families.

“I hope they understand there is a historic opportunity to change reality through a draft law,” she said. “We need to help the army create adapted frameworks and lead ultra-Orthodox political figures and rabbis to change their approach. Together, to build a partnership in sustaining the Jewish people, in the only place it can live.”

Looking ahead to 2026, Krisi shared the hope she holds.

“That what’s happening in the country will drive young people into the streets,” she said. “They are the future. The responsibility is on them to build a different reality and society here. I believe the question shouldn’t be what I feel like doing or what I have energy for, but what is right to do now, what is required of me.”

‘In the field I’m at war, and in the Knesset I’m fighting a battle’

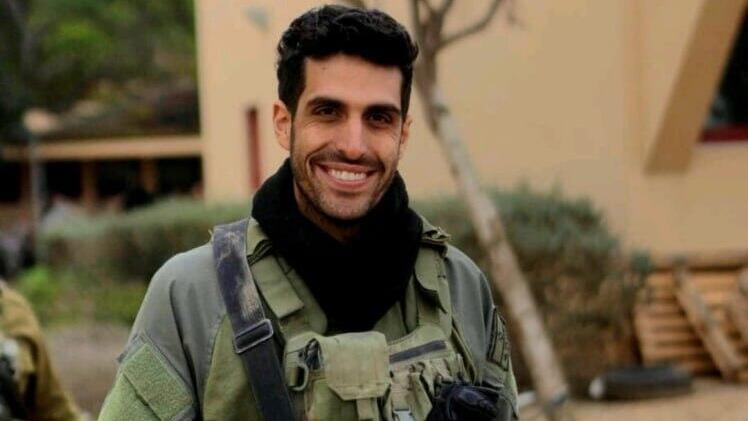

Warrant Officer (res.) Nir Issachar, currently serving on the Lebanon border, is fighting to raise awareness of the price reservists pay.

“If we continue in a loop of rotation after rotation, we’ll collapse,” he said.

After serving about 350 reserve days as a commander in the 55th Brigade, Issachar is now in his fifth reserve rotation on the Lebanon border. At home in Givat Yeshayahu await his wife, Miriam, who is currently pregnant, and their two daughters: Hillel, 5 and a half, and Noam, 2 and a half.

“We lost a teammate, Nitzan Sessler,” he said. “On Simchat Torah last year, we lost Yedidya Bloch and Guy Ben-Harosh. Twice I was almost killed, a matter of a second one way or the other.”

Issachar said those losses and near-death experiences led him to act publicly.

“I decided I didn’t want to return to the routine we had before the war. I understood we had to talk about the reservists,” he said. “As a member of the leadership of the ‘Fourth Quarter’ movement, which seeks to change Israeli society, it also has to lead this issue.”

As a commander in the field, Issachar said he knows firsthand the personal prices paid by reservists and their families.

“People whose partners had miscarriages and they weren’t there the next day. Guys whose businesses were broken into at night while they were in the middle of a rotation. Students who dropped out of degree programs and realized they couldn’t continue. This is our daily reality, even before the larger manpower crisis in the IDF,” he said.

That personal familiarity led him to raise his voice in the Knesset.

“There was no one to speak for the ordinary soldier at the edge,” he said. “We understood that if we keep going in a loop of rotation after rotation, we’ll collapse. In the Knesset, our goal is to raise the challenges of burnout and clarify the price.”

“Most lawmakers didn’t serve in the IDF or weren’t combat soldiers,” Issachar added. “If we don’t explain to them the cost to relationships, children and work, they won’t understand. Even now, when I share, I’m not sure they understand, but I know I’m giving voice to the few percent who serve.”

He said with frustration that reservists are no longer invited into discussions.

“It’s absurd,” Issachar said. “I arrive at the Knesset with the same energy I report for reserve duty. On the ground I’m at war, and in the Knesset I’m fighting, instead of the people who represent me fighting for me. We’re not supposed to fight for something that should be self-evident, appreciation for our contribution. We earned the right to say what we need.”

Issachar said he is proud that his fighters have shown 100% turnout, but warned how fragile that is.

“It’s one punch,” he said. “The moment two or three break, it affects everyone. In our last team meeting we already talked about the difficulty of reporting for the next rotation, which again falls during summer vacation and the holidays. Again away from family and life.”

‘Rehabilitation doesn’t end when you leave the hospital’

Master Sgt. (res.) Or Shizaf, 36, from Mitzpe Ramon, was wounded in Khan Younis, underwent long rehabilitation and now asks only one thing.

“Remember that the person standing in front of you may be carrying something heavy,” he said. “We all need to be more inclusive, kinder and more patient.”

Shizaf was called up on the morning of the October 7 surprise attack moments after completing a 26-kilometer run.

“In that moment, it was clear I was reporting,” he said. “I still didn’t understand the scale of what we were entering.”

In civilian life, Shizaf is a running coach and educator. He served in the 5th Brigade, 8111th Battalion, until he was wounded.

“I thought they’d take us for a week or two to the line to replace ‘real soldiers,’” he said. “Then we went into clearing the communities near the Gaza border. It took time to understand we were becoming a significant force in the war.”

“The realization came during a clash with a terrorist near Kissufim on October 12. In hindsight, we learned he was the last terrorist in the kibbutz.”

Three fighters were wounded in that clash, and Shizaf said he experienced combat shock.

“My head worked sharply during the event. I fired, reported on the radio, treated the wounded,” he said. “After the evacuation, my head slowed down, I couldn’t concentrate, and everything was very frightening. It took me several days to recover.”

On December 10, 2023, during an operation in Khan Younis, Shizaf was wounded again.

“We went on a raid of a house in a UNRWA school complex with intelligence about hostages,” he said. “When we found a tunnel entrance in a nearby yard, explosives were detonated on us. I was seriously wounded, three others were wounded, and five were killed.”

Only after waking from surgery did he understand who was gone. “The pain has accompanied my rehabilitation ever since,” he said.

Shizaf was evacuated to Soroka Medical Center, where he underwent four hours of surgery and was hospitalized for two and a half months in rehabilitation.

“In the first days I was completely dependent,” he said. “Out of four limbs, only my weaker hand functioned. I was wounded in both legs and my right arm. The bones in my left foot were shattered. As a runner, I asked them to treat my legs first. For me, they are breath.”

It took him six months to return to running. What remains most vivid for him is the embrace he received from society after being wounded.

“At first, they wrapped us in love,” he said. “People came to the hospital, said they cared, said thank you. It gave us strength to lift our heads and start rehabilitation.”

Looking toward the new year, Shizaf shared an important message.

“Rehabilitation doesn’t end when you leave the hospital. In some cases, it never ends,” he said. “People don’t see my scars. They don’t know I’m wounded. The consequences are sometimes invisible. Remember that the person in front of you may be carrying something heavy. We all need to be more patient and tolerant. It will make us a better society. The war may be officially over, but our rehabilitation as a society is just beginning.”

‘I want recognition for our sacrifice’

Order after order, rotation after rotation, the responsibility for holding the home fell on Noga Eliasaf. “Now we’re learning how to live again as a family,” she said.

Her partner, Capt. Tomer Eliasaf, 35, a fighter in the 8th Brigade, completed about 450 reserve days during the war, including officers' training. Each time he reported, he left behind their children, Oz, 12, and Maayan, 3.

“We were at a holiday gathering with family in the south, about half an hour from the Gaza border,” Noga recalled of October 7. “Everyone was religious, observing Shabbat, so we weren’t on our phones. My brother-in-law heard calls on the radio and went out to evacuate the wounded as an ambulance driver. When he returned, we understood the scale.”

Her brother-in-law was later maneuvered in Gaza and was critically wounded.

“From that day, Tomer left, and we understood we were entering this deeply,” she said. “He left without knowing what he’d face. We didn’t know when he’d return.”

11 View gallery

'Learning now how to live again as a family,' Noga, Tomer and their children, Oz and Maayan

(Photo: Yariv Katz)

As rotations accumulated, Noga said the sense of isolation deepened.

“I lost patience. I felt alone,” she said. “Reservist families and the rest of Israeli society feel like parallel worlds. People tried to normalize his repeated absences, so I stopped sharing and asking for help.”

The economic toll followed.

“Tomer lost his job due to extended service,” she said. “Since then, he’s been on unemployment between rotations. I haven’t been able to return to my profession. I didn’t have the time or capacity.”

Looking ahead to 2026, Noga said her message is simple.

“I don’t want thanks or to be called a lioness,” she said. “I want recognition of our sacrifice. We need understanding from workplaces, schools and society. Sensitivity and patience. We’re learning how to live again as a family, like every reservist family, when at any moment someone is called up or already on a rotation.”

‘The thing that keeps me sane is music’

The business collapsed, debts piled up and his baby grew up far from her father, but Osher Partuk did not give up reserve service.

“I understood I was fighting for home,” he said.

Master Sgt. (res.) Osher Partuk, 32, from Lod, is married to Simcha and the father of two children: Ranel David, 5, and Tevel, 1.

For more than two years of fighting, Partuk completed about 405 reserve days as a vehicle officer in the 16th Brigade and is now on another rotation expected to last about 60 days.

Because of his service, his events business suffered a sharp blow. “It was hard to get released for events,” he said. “Productivity dropped by about 50%.” He took out a loan to survive.

“The bank refused. My wife’s boss helped,” he said. “It hurts. Like a knife in the heart.”

Despite the cost, his commitment did not waver. “I understand I’m fighting for home,” he said. “I have 15 soldiers under me. If I don’t come, their morale drops.”

Partuk also carries loss. “Ten minutes after we switched, my friend Sgt. Maj. (res.) Mordechai Yosef Ben Shoam was killed by an explosive,” he said. “Every time I enter Gaza, it costs me, but it also drives me.”

At home, the impact is visible. “My five-year-old begs me not to go,” he said. “He asks to come with me to Gaza. It’s absurd.”

What keeps him going is music. “When I play, it heals me,” he said. “I wish we could return to real life. That’s the most important thing.”