“When we took off, we knew nothing. On the radio, they told us there was concern about an infiltration at Zikim. On the way, they changed the message and said it wasn’t Zikim but Re’im. Originally, the leader was Deputy Squadron Commander B. At 7:40 a.m., close to the Re’im area, we split the formation, and I took the lead and the communications with the division headquarters. ‘They’re at the gate,’ we heard on the radio. We arrived above division headquarters, and a shoulder-fired missile was launched at us, very close, and right after it, another one. We managed to evade both missiles, and then a third one was fired. ‘Our border has shifted,’ I told the formation. ‘From now on, the border is Re’im.’

“Near the guard post of division headquarters, I noticed several figures. I didn’t know if they were our soldiers or terrorists. I saw them running toward an orchard adjacent to the gate of the base. By the gate were several cars, all with open doors, but no one was inside them. I didn’t understand what was going on. At the division, they couldn’t tell me for sure whether there were any of our civilians among the runners. Without receiving permission, I fired a missile near the entrance to the division headquarters. I wanted to create order and understand who was who. I also authorized the second helicopter in the formation to fire a missile at the other side. It was not an easy decision. At that stage, we feared we were causing more damage than benefit.”

— Lt. Col. (res.) Tavor, from the book War Machine – The Faces Behind the Helmet: Attack Helicopter Pilots Tell Their Story

Oct. 7, 2023, 6:40 a.m. Lt. Col. (res.) Tavor (all names in this article are pseudonyms for information security reasons), an attack helicopter pilot in Squadron 113, was on routine holiday standby and already awake. He had time to check the red-alert warnings in the Gaza envelope when the sharp sound filled the squadron at Ramat David Airbase in the north: a scramble.

“Something there felt odd,” he recalls this week. “Usually, there’s no logic in scrambling two attack helicopters from the north to the Gaza envelope. An attack helicopter cannot deal with Grads, Qassams or rockets fired from Gaza. There’s Iron Dome and other systems for that.”

At the same time, driving south in his car was Maj. (res.) Boaz, a helicopter pilot from Squadron 190 based at Ramon Airbase. Four years earlier, Boaz had helped draft the “eruption protocol” for sudden incidents. In an emergency, it was determined in advance that he would serve as the squadron’s battle manager.

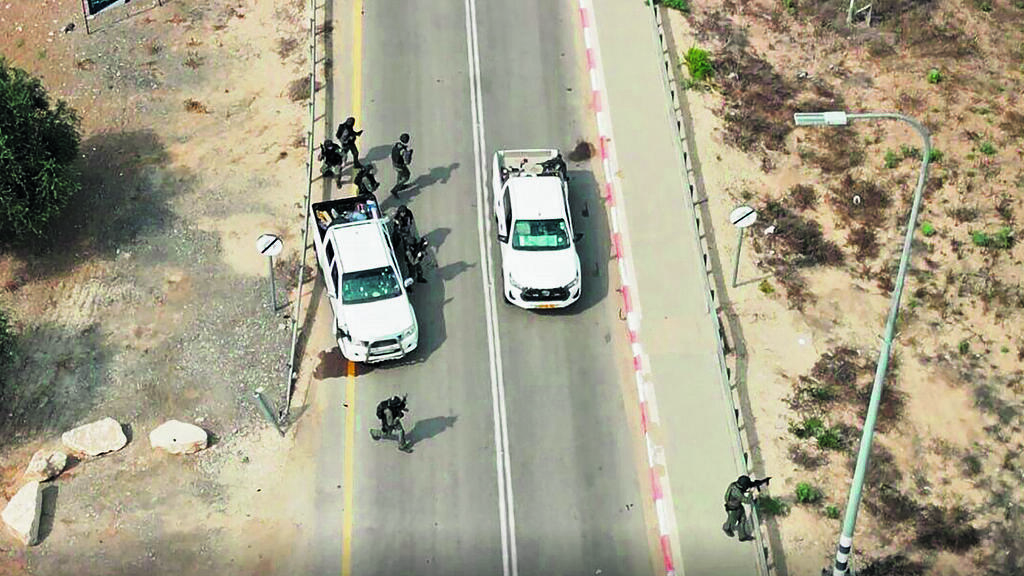

“With all the shutdowns of the helicopter squadrons,” he explains, “the IDF Operations Directorate decided that standby would sit in the north. So in our squadron, we ‘invented’ a protocol for a rapid response in the south. We had trained extensively withthe Gaza Division and the regional division responsible for the Egyptian border. So when I saw the pictures of the pickup trucks that morning, it was clear to me this wasn’t people who had crossed a tunnel or accidentally breached the fence — something big and bad was happening at the division. We always trained for an exaggerated scenario. In reality, it wasn’t even close to what happened. Reality was far bigger than what we drilled.”

“Maybe it’s unfair to say, but when they said ‘the diamonds are in our hands,’ my thought was that it referred to Kfir and Ariel Bibas, may they rest in peace. I thought it was strange to call two adults ‘diamonds.’ I assumed they meant children — little diamonds.”

The day before, Oct. 6, 38-year-old Boaz had called his squadron commander to announce his resignation. The background was the decision (later canceled after Oct. 7) to shut down Squadrons 190 and 113. The Apache, it was argued, was too expensive and it was better to invest in drones.

After leaving permanent service eight years earlier, Boaz had worked as a commercial airline pilot and devoted time to cycling. He felt he was no longer needed in the attack helicopter array. As a father of three young children, ages seven, five and not yet two, he preferred to spend more time with family. But his commander did not answer the call, and Boaz postponed the conversation to the next day, which, of course, never came.

In the first 24 hours, he functioned as battle manager, then handed the role over to regular personnel and went up himself in a helicopter. “But the first two hours,” Boaz says this week, “were the formative event of the war for me. To be in operations, with the sense that everything above you had collapsed, that systems weren’t functioning, that there was no one to talk to, in total uncertainty, while people were being killed and murdered — that’s a hard feeling. Those in the air also faced great difficulties. Everything was a matter of life and death. It’s not easy being in a position where every word or action determines whether people live or die. At first, I carried a lot of anger about everything that didn’t work that day. I felt ashamed to be part of a defense system that failed.”

A call from a soldier’s mother

Much criticism was heard, and still is, about the performance of the attack helicopter corps that morning. “Where was the air force?” cried Gaza envelope residents, Nova festival participants, and parents of soldiers in western Negev bases.

The new book by Meirav Halperin, War Machine – The Faces Behind the Helmet: Attack Helicopter Pilots Tell Their Story (Yedioth Books), describes the events of Oct. 7 through the eyes of those in the cockpits. One is Lt. Col. Tavor, 48, married and father of four children, ages nine to 20. He retired from permanent service five years ago and now works in hi-tech while also leading social initiatives to connect Israel’s periphery with elite IDF units.

On Oct. 7, Tavor was among the four pilots of the two Apaches that took off from Ramat David and were the first to reach the envelope. “That was the hardest dilemma I faced that day,” he says of the decision to fire missiles near Gaza Division headquarters. “In general, the first missile launched from a helicopter is the hardest of the sortie, even if it’s the second or third mission that day. There are a few seconds until it hits the ground, and in those seconds, you don’t breathe, waiting for it to strike properly. Once they tell you, ‘it’s OK, keep going,’ the second one is easier.

“I cried several times,” Boaz adds. “For example, after the anger gave way to the realization of how many people were kidnapped, murdered, burned — everything that happened, together with the voices and the phone calls from operations, it just came out as tears. Tears of sadness.”

“In my case, the first missile was right near the entrance to Gaza Division, around 8 a.m. Every parameter was against us. It was inside Israel, at the division headquarters. This wasn’t one soldier fighting — it was a whole division HQ with who knows how many inside, not just ten. Cars were driving on the road, and we couldn’t say if they were civilians. You think: what if I’m wrong, what if the controller on the ground doesn’t understand the picture or even points me the wrong way? The officer guiding me did an amazing job, but you could hear in his voice that it was the first time he had ever spoken to an attack helicopter. Later, I found out it was a lieutenant who had just arrived at the division war room.”

Months later, Tavor received a surprising call from the mother of a female soldier at the division. “She told me, ‘Thanks to you, my daughter is alive.’ At a meeting we held, I told her: ‘I didn’t save your daughter. I’m glad she’s alive, but I won’t crown myself with laurels that aren’t mine. It’s very hard to link one action to one outcome that day.’ From her, I learned that the lieutenant guiding me was the same one. I left that meeting strengthened.”

Did you ever meet the lieutenant?

“No. Afterward, I entered a year of war, and now we’re already two years later. I think I have a tendency to move forward, and I chose not to dwell on things that won’t help me. What I was interested in was whether we were effective. In the end, the ones who shouted loudest on the radio were the ones who ‘got’ us, the air support, and you think: if I hadn’t been at Re’im division, maybe we would have saved someone else. Just a month ago, I was told our fire probably disrupted the takeover of the division, because that Nukhba company, which tried to link up with militants already inside the base, turned away from the gate and fled.”

At the same time, a handful of officers and soldiers under the command of the division’s tracker officer fought a heroic battle inside the base. Later, commando unit Shaldag joined, led by its commander. Some of the militants who barricaded themselves inside the gymnasium were eliminated by fire from another helicopter that arrived at the scene.

The escape from Nova

Lt. Col. (res.) Tavor: “I couldn’t understand how there were no military forces on the ground — only militants. I announced to everyone in the air that they had crossed the fence, that there were terrorists on our territory, and that I had already fired inside Israeli territory. I said it in order to break for the other pilots the psychological barrier against firing on our side of the border. In routine, it is strictly forbidden to fire in our territory, and I wanted to make clear to the rest of the formation that we were in a new reality.

“We had run out of munitions. Fuel in the helicopter was running low. I flew quickly to the base to refuel and rearm. On the way, I saw convoys of civilian cars, hundreds of them, some driving, some stuck in traffic. I had no idea what all those vehicles were doing there. Only later did I realize these were the cars fleeing from the Nova party.

“When I landed at the base, the first and only thing I said to the pilots waiting on the runway to take off was: ‘There’s a war, I fired in our territory, they’re shooting at us, I’m out of ammo.’” (from the book)

“A few weeks after Oct. 7,” Tavor recounts, “I attended an Air Force event and spoke with someone who had once commanded Squadron 113. He asked me to tell him about that morning from my perspective. Only then did I realize I needed to sit with myself and with the footage before I started mixing up missions, because I had done so many and the days blurred together in my memory.

“One day blended into another. I watched every video, minute by minute, several times, and then I corrected myself. For example, after the strike at division headquarters, I went to another dilemma, of a kidnapping incident, where the target was a vehicle supposedly carrying kidnapped soldiers. Again, I was in discussion with that same lieutenant. I remembered that event as taking place at Kerem Shalom, but later I discovered it was actually at Khan Younis.”

And do you know who the soldiers were? Was it really a kidnapping?

“I don’t know, because I don’t check. That’s what keeps me professional. I don’t say it proudly — maybe it’s just the defense mechanisms I need for myself.”

Tears of pilots

Maj. (res.) Boaz: “I started handing out missions and declared the eruption protocol. For the technical crews, it meant they didn’t check helicopters in the usual way, just fueled them, loaded missiles, and launched. ‘We’re in battle protocol,’ I told them. ‘We need as many helicopters in the air as possible. Every helicopter gets fuel, weapons, and flares and goes up. Don’t hold us back — just bring us helicopters.’

“I understood every minute on the ground cost lives. Calls began pouring into the squadron from the field — operations officers, watch officers, staff officers, people we had trained with for years, and suddenly they couldn’t get an answer anywhere else. They called us out of desperation and helplessness.

“All the calls were in the same tone: ‘They’re shooting at us, we’re holed up, they’re closing in on us, militants are overrunning us.’ In some calls, I heard screaming and gunfire in the background. Those were the worst two hours of that day for me.

“After 24 hours, I left operations to rest, but I couldn’t sleep. I thought about the time wasted, asked myself if maybe we could have prevented civilian and soldier deaths. I began to cry. After I calmed down, I returned to the squadron.” (from the book)

“I cried several times,” Boaz adds. “For example, after the anger gave way to the realization of how many people were kidnapped, murdered, burned — everything that happened, together with the voices and the phone calls from operations, it just came out as tears. Tears of sadness.”

Two weeks ago, a video was published claiming helicopter pilots deliberately did not fire. At Be’eri, there were claims that if the road leading from the kibbutz to Gaza had been bombed, so many people would not have been kidnapped.

What do you think, as pilots who were in combat helicopters that day?

“I also could have ordered the bombing of the road at Be’eri,” Boaz replies, “but what if a ground force commander was planning to enter there, and then you block his route? At that stage, when command and control were not functioning, missions went out through operations. It wasn’t that someone in operations dispatched a squadron and could tell them: ‘Bomb this.’

“Understand — it took a whole year until they built a complete enough picture to debrief. Do people expect a combat crew to understand the battlefield picture in three minutes? There were cases where our fire hit our own forces, and cases where not firing saved our forces. People on the ground thought everyone around them was the enemy. If we had fired without understanding at whom, much of that fire would have been on our own troops.

“But to say there were pilots who could have fought the enemy and chose not to? I can’t think of anyone who truly believes that.”

Lt. Col. (res.) Tavor: “I’m not here to defend the air force, but when I hear people saying, ‘Where was the air force,’ I say — even as a civilian — you have to understand the limitations of the platforms. In the end, you scramble with an attack helicopter, it has a limited number of missiles and munitions. Despite its immense power, it can’t stop 3,000 people running.

“In Re’im live the parents of an air force officer who was in the control room that morning. He had the greatest interest in bombing there, and still it didn’t happen. Why? Because the central problem was command and control, and the link between need and capability. That’s for the commission of inquiry to explain — how we got to that situation.

“On that day, every person in the envelope who needed help and saw a helicopter flying overhead surely asked himself: ‘Why isn’t it spraying?’ But maybe that helicopter was on its way to Kerem Shalom, because someone demanded it, and no one told him: ‘We need you here, too.’

“And if people are in a shelter, should their fate be to die by helicopter fire? Who gave us the authority to decide life and death? I’m sure I could have done things better, and I’m sure I didn’t do some things well enough. But overall, I stand by every munition that left my helicopter.”

And yet, if you appear before a commission of inquiry and they ask you, “Where was the air force?” what do you answer?

Tavor: “The key to successfully defending in this sector is communication between ground and air forces, and in my view, that communication collapsed. As a result, we lost a large part of our ability to deliver fire from the air to assist communities and outposts. The air force found itself with a lot of power but didn’t know where to put it. Add to that the fact the whole event happened in our own territory.

“It’s not as if someone came and said: ‘Guys, all the white pickup trucks are enemies,’ or: ‘From this road westward, everyone is an enemy.’ In reality, in the greenhouses, there are enemies, in the houses, there are enemies, and you have to make decisions within seconds with the one missile you have left.

“And then you say: ‘I take upon myself the decision to fire at a house I know has militants inside,’ when from the air I cannot know where the safe room is. Should I be the one to make that decision? Every helicopter faced incredibly complex dilemmas, and that day required breaking all the rules.”

Six months after the war began, Boaz’s squadron gathered. “My squadron commander and I stood in the hall,” he recalls, “and I said to him: ‘I’m looking at all the empty chairs, and there are quite a few — but it’s still fewer than the number of people murdered on Oct. 7.’

“And he replied: ‘True, but look at all the buildings behind this hall. If you hadn’t done what you did, they would also be gone.’ He shifted the focus not only to what we lost, but also to what we managed to save.”

The kindergarten teacher’s son was killed

Maj. (res.) Boaz: “In the first two weeks of the war, every message about a hostage, every body discovered in the field, every ‘now cleared for publication’ brought me back to Oct. 7 — to a searing personal debrief, to the question whether I could have done something more. I was filled with anger and poison at everyone involved, including myself.” (from the book)

“I came home for the first time after about a month. The moment I entered the house I saw the kids. I spread out my arms and they ran to me. I lay on the floor on my back and we hugged for minutes without moving.”

“I remember one body that was shot in a certain community and was found in a terrible condition,” he recalls. “You try to understand if there was a moment of overlap between you and the person lying lifeless by the fence.

“In the first three days, you focus only on combat, putting aside the pain and the questions. But afterward, you discover more bodies burned, or reports of hostages taken from this community or that outpost, disappearing without a trace. Places the IDF didn’t reach, and you are part of the IDF.”

Were there cases where you connected a name to an incident you were part of?

“Not a face, but names, events, places. There is no place where an air crew — whether helicopter or drone — saw an enemy and did not fire. The case of Efrat Katz, may she rest in peace, who was abducted from her home in Nir Oz and apparently killed by helicopter fire, affected me. It’s impossible not to be touched by that.

“The knowledge that things I said or did saved lives or not — that’s a heavy burden. You process it over time to be able to keep living with yourself, but it doesn’t disappear.

“The war changed how I carry out both my ground and aerial roles. Today I know I need to exercise more judgment and far more doubt. To also do the staff’s job of thinking and planning. I don’t question the mission itself — only the way.”

Where does that take you in private life?

“I can go with the kids for ice cream, and near us are posters with photos and names of hostages and victims. With one quick glance, I recognize details familiar to me.

“Or when I’m at a picnic on Saturday, on the grass, with blue sky and my children around me, and suddenly the thought passes: how many families like this have vanished? And I know there are children who will never again run with their parents.

“My son was two when the war broke out, and now he’s almost four. In that time, he learned many things like his peers — even toilet training — but he also learned what death is. His kindergarten teacher lost her son in the war, and now he knows her son is dead.

“I came home for the first time after about a month. The moment I entered the house I saw the kids. I spread out my arms and they ran to me. I lay on the floor on my back and we hugged for minutes without moving.”

Closing a circle at Rafah

In May 2024, Tavor closed a circle when he took part in the operation that rescued hostages Luis Har and Fernando Marman, abducted from Kibbutz Nir Yitzhak and freed from Rafah after 129 days in captivity.

“Maybe in 20 years someone will make a film about all the things that happened in this war,” he says. “I was in many events worthy of a full day of study and debriefing, yet they passed us by too quickly to dwell on. I was in a hostage rescue, in special operations, we did things very professionally, very challenging.

What I was interested in was whether we were effective. In the end, the ones who shouted loudest on the radio were the ones who ‘got’ us, the air support, and you think: if I hadn’t been at Re’im division, maybe we would have saved someone else.

“As a pilot in the operation that freed Luis Har and Fernando Marman, you realize the enormous dissonance between the IDF’s and security forces’ strength and capabilities when planning and initiating — versus when an event comes as a surprise.”

Describe what went through your mind when you realized the operation had succeeded and the hostages were freed, especially after the air force failed to prevent their abduction on Oct. 7.

“I was very emotional. I cried a little to myself — I cry inwardly, that’s my built-in problem, as my wife says. I was very moved. At the time, I didn’t know it was them. Only afterward did I understand.

“Maybe it’s unfair to say, but when they said ‘the diamonds are in our hands,’ my thought was that it referred to Kfir and Ariel Bibas, may they rest in peace. I thought it was strange to call two adults ‘diamonds.’ I assumed they meant children — little diamonds.

“So in the air, when I heard that report — because again, each of us is exposed only to what he needs to be — I was sure it was the children. I said: ‘Wow, I hope they’re alive.’ Then came the report that the rescued were alive, and again I said: ‘Wow.’”

And then you discovered they weren’t the Bibas children.

“Correct. It was mixed emotions — joy at the lives saved, and disappointment at those who weren’t.”

Today, after 450 days of reserve duty, hundreds of sorties, and tons of munitions fired (“Today a young crew member in the squadron fires in a single week as much ordnance as a veteran once fired in his entire career”), Tavor has quite a few insights he didn’t have before Oct. 7.

“First, the concept of ‘lead independence’ sharpened for me — the need for autonomy in decision-making on our platform, with all its uniqueness. The freedom we need to receive and to demand.

“Second, I understood that although in the air force you cannot do without obedience, you must be highly professional to also know when to break the rules. And for that, you need to understand the system very well, and the rationale behind the rules.

“And finally, and this is important to stress, I am part of the military failure of that day. When I tell my story to anyone who wants to hear, I say: ‘Guys, I’m telling my personal story.’ It’s not a combat legacy with any kind of victory. It’s part of a military failure, in which I did the best I could.”