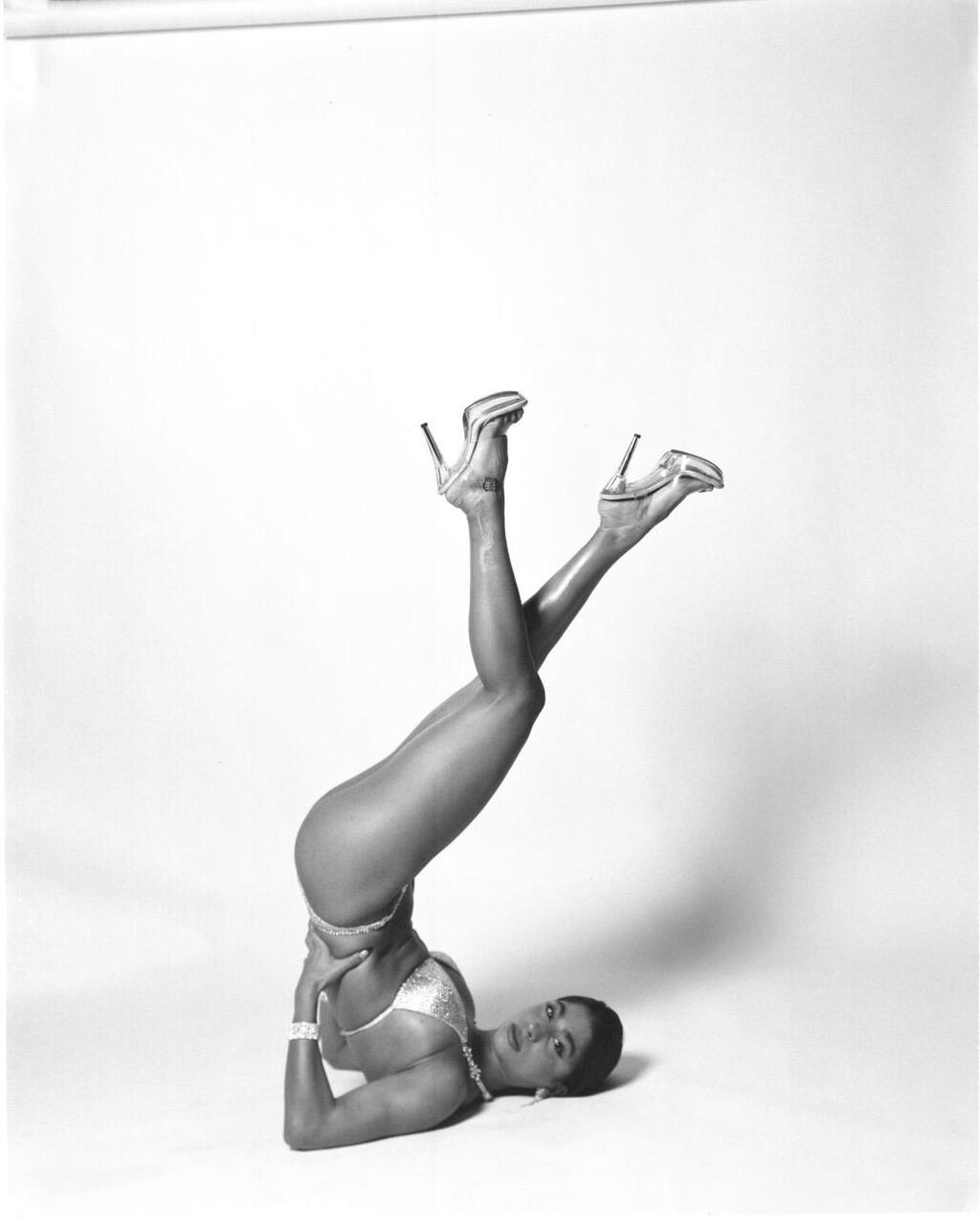

Stav Shalom emerges from a black-and-white photograph, her body inverted on the floor, legs extended upward at a sharp angle, transparent heels pointed toward the ceiling. Her muscles are taut yet restrained, her face calm, almost indifferent to the strain her body conveys.

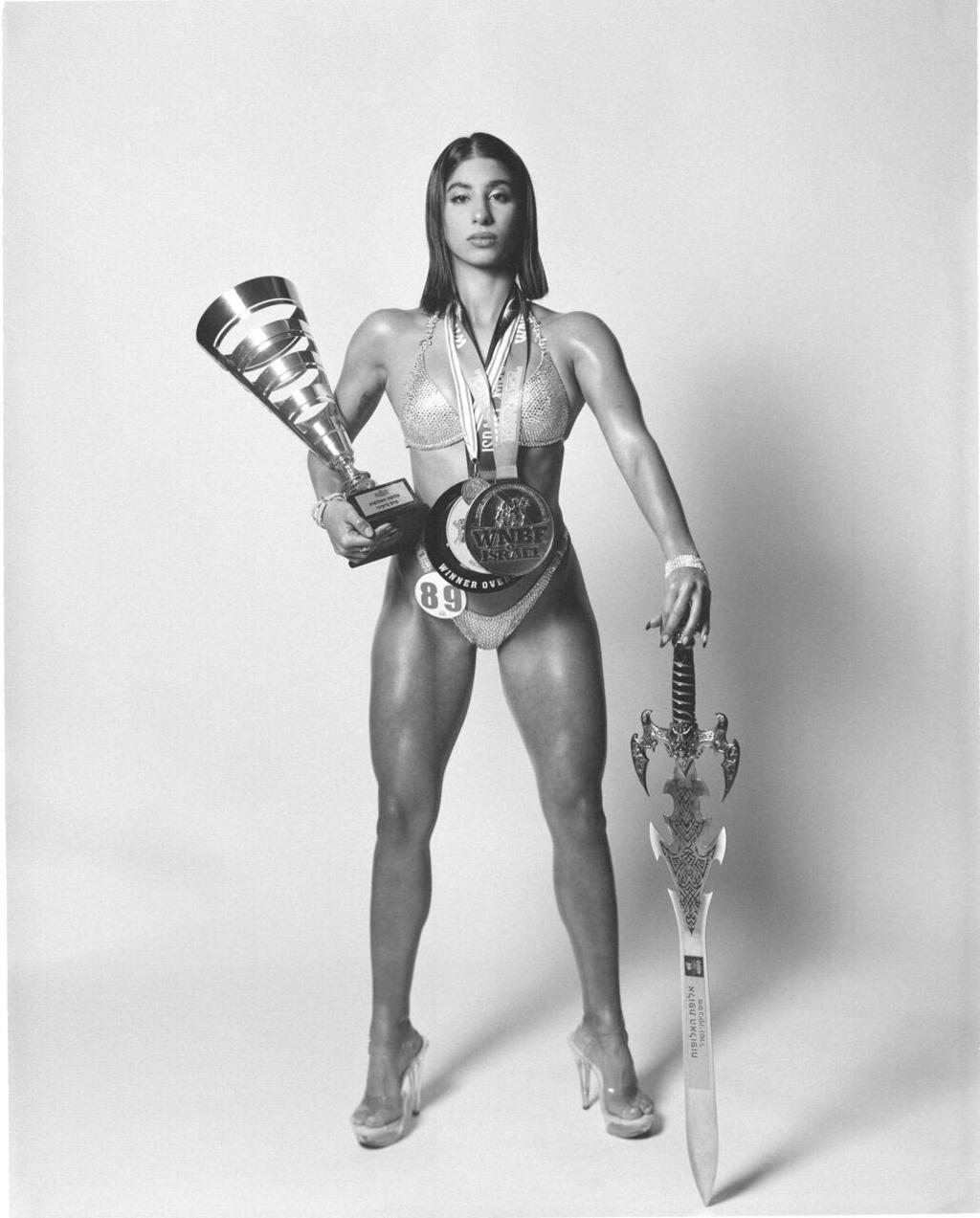

In another image, she stands upright, facing the camera head-on. Her gaze is steady, her muscles sharply defined, a shimmering bikini hugging her body. A heavy medal hangs from her neck. In one hand she grips a trophy, in the other a decorative sword, a theatrical prop that blurs the line between athletic competition and a mythic Amazonian figure.

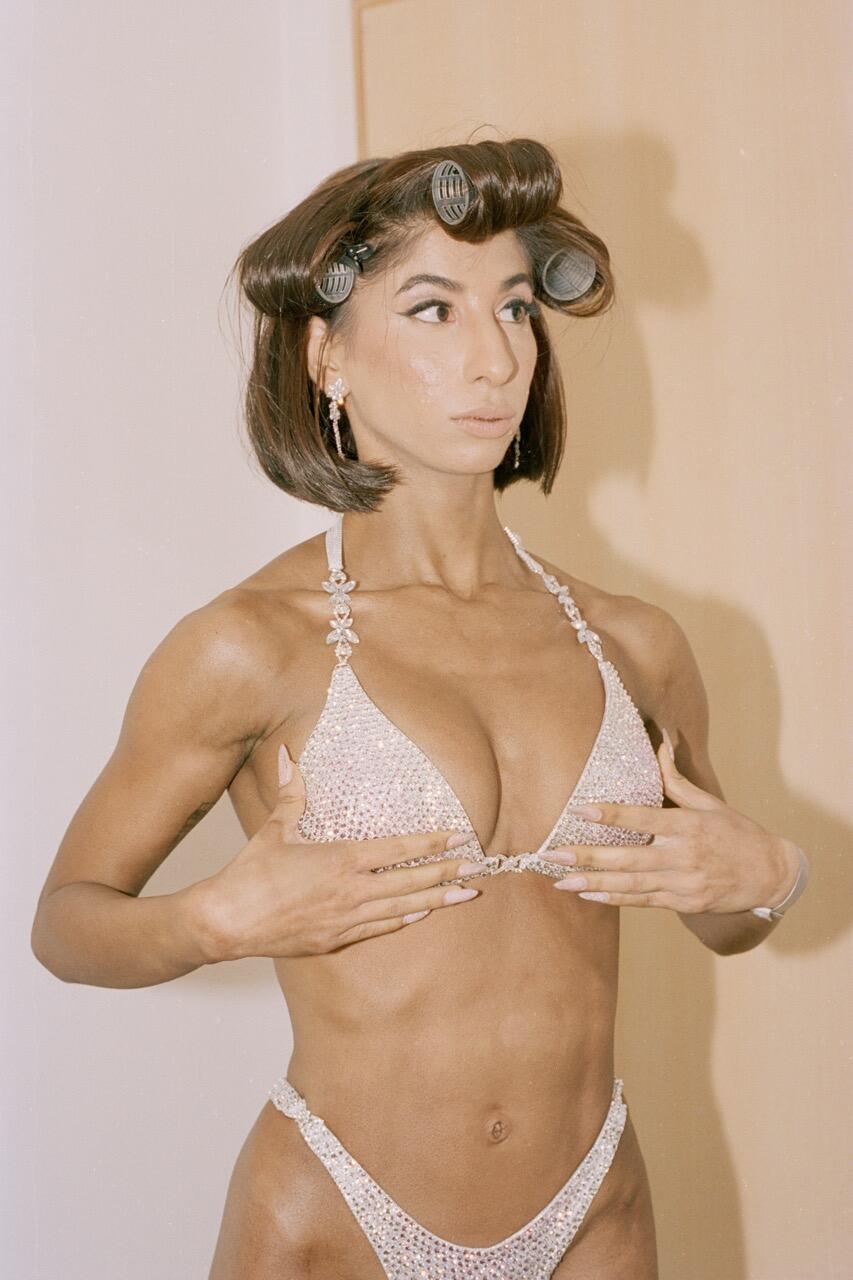

In a third photograph, rendered in softer colors, she appears backstage, moments before or after stepping onto a bodybuilding stage. Her hair is rolled into curlers, her eyes cast to the side, as if briefly withdrawing from the performance itself.

A casual viewer might assume the images tell a story of strength, discipline or control, of a body meticulously built. But those familiar with the story behind them know they conceal a very different narrative: that of a young woman who suffered from eating disorders and found her way out through bodybuilding. And another story, just as central, of two sisters, one in front of the lens and the other behind it, documenting not only a body, but the difficult path that shaped it.

Stav Shalom, 23, grew up as an outstanding ballet dancer. “I was a dancer before bodybuilding,” she says today. “I studied at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance and danced with Ballet Jerusalem, which is considered a very prestigious studio in Israel. The eating disorder developed over time. I’m also, by nature, a very extreme person. The drive for perfection was always there, and ballet represents an ideal that is, in a way, impossible.”

Asked when it began, she pauses. “You can’t really pinpoint a single moment, because it’s something that builds,” she explains. “It took me a long time to understand that something was wrong with my body and my mind. It started when I realized ballet would be my life career, and I decided to give it more gas: eat ‘clean,’ train harder, put it above everything else. I prioritized it over social life and normal pleasures, like going out with friends. And suddenly the thin line between sanity and extremity grew very wide.”

What begins as a seemingly reasonable decision — eating right, training properly, putting a career first — quickly turned into the familiar and troubling chronicle of an eating disorder: a daily negotiation over the right to eat, disguised as perfectionism.

“It became a fear of food,” Stav says openly. “From there it rolled into something much more emotional. If I felt I wasn’t good enough at ballet, I felt I had to pay for it somehow. I felt I didn’t deserve to eat. That if I lost more weight, I would look physically smaller and feel the way I already felt mentally — small.”

She pauses again. “Over the years it became easier for me to talk about it,” she says. “I didn’t eat. If I did eat, I vomited, because my parents eventually became worried. People around me noticed. I hid food. The lowest weight I reached was 39 kilograms.”

Eventually, it was her body that refused to keep playing along. “I had a leg injury from ballet that wouldn’t heal, because my body was already completely depleted,” she recalls. “My father took me to the emergency room at Hadassah Hospital. They ran extensive blood tests and saw that my body was on the verge of system collapse. I was taken to the head of the psychiatric department. He asked me very personal questions, and I couldn’t answer with my father in the room. It felt forbidden. Like I couldn’t sit there and talk about what I was doing under my family’s nose. They asked my father to leave the room, and I told them everything. They said either I enter day hospitalization or I would be forcibly hospitalized.”

From Hadassah she was referred to her health fund’s mental health center: psychologist, nutritionist, weigh-ins. “Honestly? It didn’t really help,” she says bluntly. “I tried, but mentally I was so locked in, and I loved that voice in my head that told me, ‘You’re not enough.’ I believed it.”

Then came 2020. The pandemic shut everything down, and paradoxically, that was when something shifted. “Everything stopped because of COVID. No one knew how to deal with it, and it affected my treatment too,” she says. “Suddenly your routine collapses. You sleep all day, your nights flip. It was harder for my family to watch over me. And at some point I realized I actually had something to lose in life.”

Friends began reconnecting over FaceTime. “You remember people from the past. I had cut myself off from everyone and was stuck in this lonely loop. I missed being happy, social, doing things an 18-year-old girl does. Slowly, very carefully, I started eating again. It was terrifying. I relapsed more than once. But gradually I understood that I wanted to live — and if I didn’t choose that for myself, I wouldn’t listen to anyone else.”

Recovery was not linear. She later moved to Germany and returned to dancing. “The trigger came back, but I had a framework and could ask for help, because I genuinely wanted to stay happy and deal with it,” she says. “When people asked how I felt, I’d say I felt like I was in the middle of a vast ocean, constantly swimming just to keep my head above water. Slowly, the water gets shallower. You can put your feet down. You don’t have to fight just to survive.”

Eventually, she returned to Israel — and decided to quit ballet for good. “Most dancers retire young, and many gain weight very fast. I saw it around me. I didn’t want that to happen.”

She joined a gym. “I thought it would fill the void. I got addicted very fast,” she says. Within a year she was training intensely and began working with a coach who competed in bodybuilding. A casual comment — “If you were wearing a bikini, you’d win” — changed everything.

At 22, she signed up for her first competition. She won. Then she won again. “That’s when I realized I was meant for this,” she says. “I know how to handle it. It’s healthy for me.”

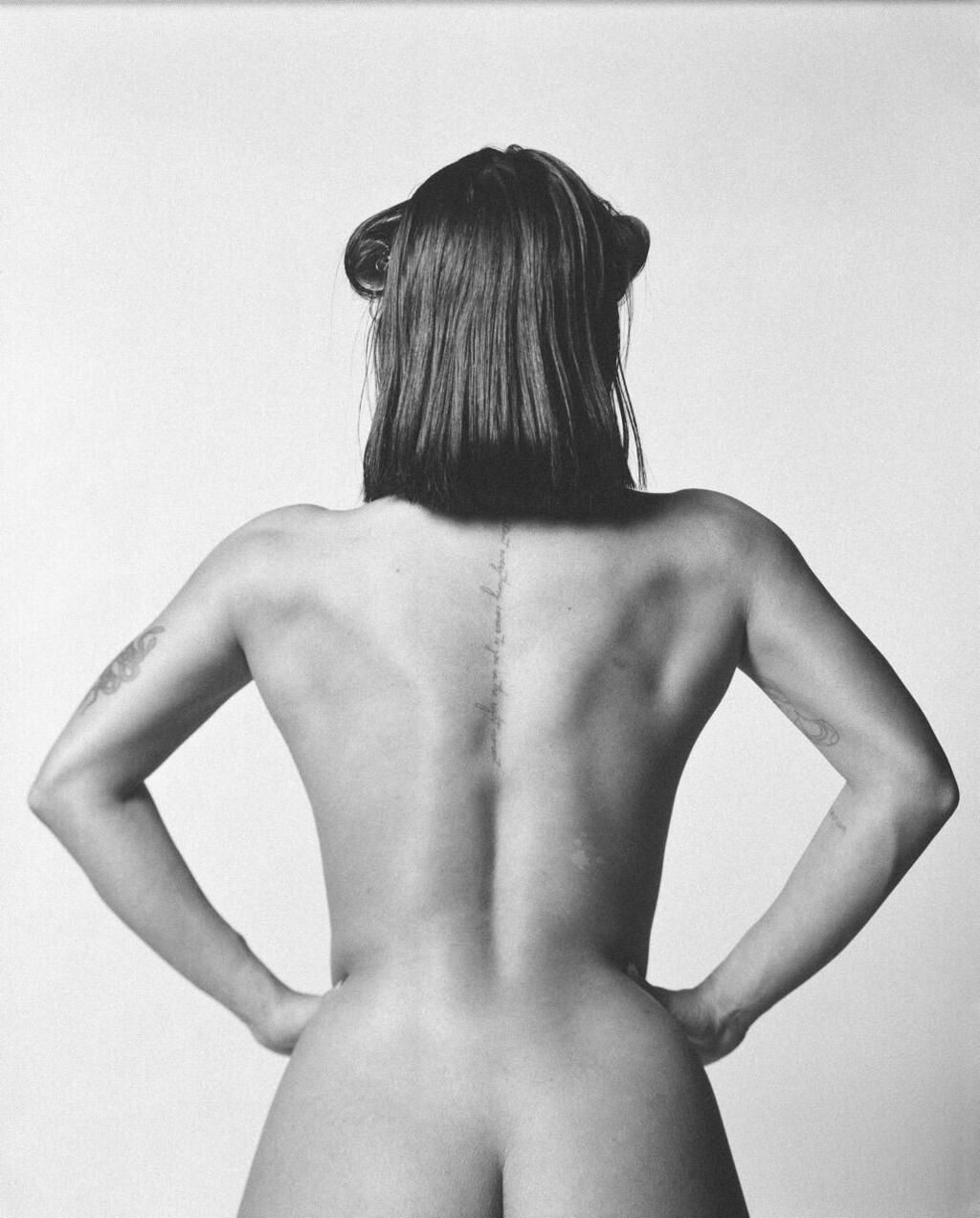

At this point, her sister Ofek, 27, joins the conversation. A photographer and Bezalel graduate, she documented the journey in an intimate project titled “Miss Bikini.”

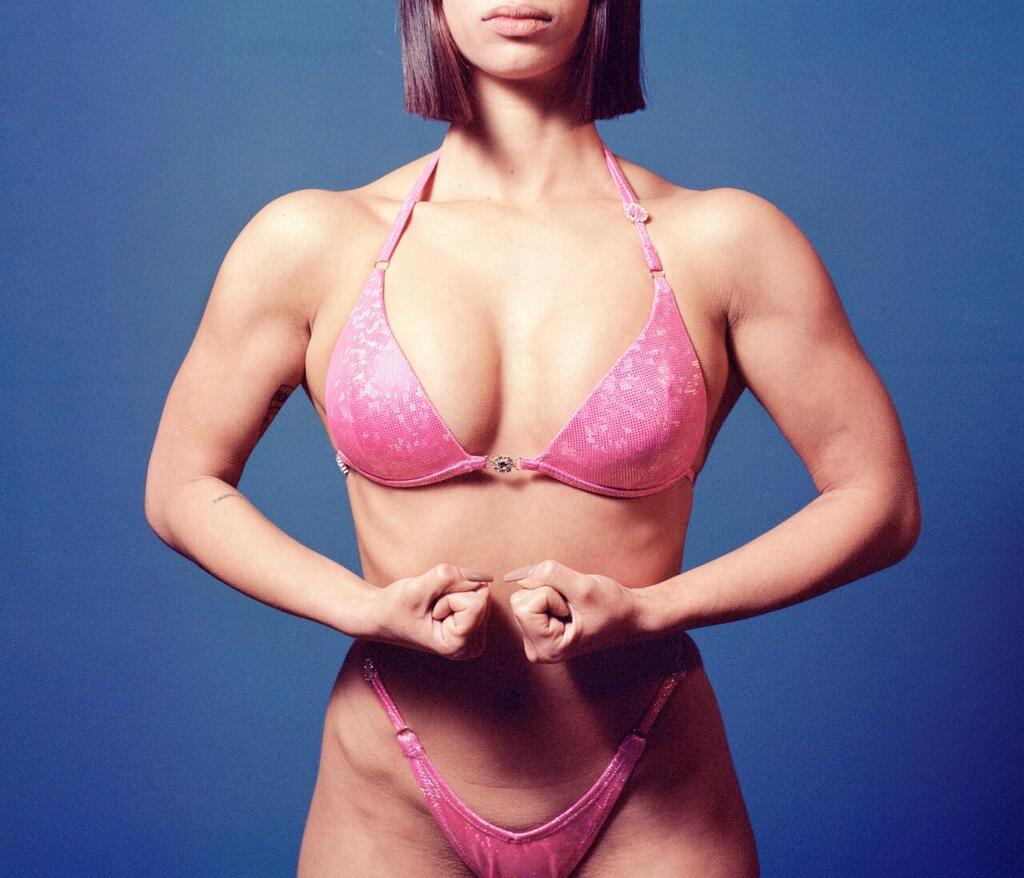

“I started the project as a final-year assignment,” Ofek says. “I was interested in the transition from the extreme femininity of ballet to the extreme masculinity of bodybuilding. The dissonance is enormous.”

The project began on competition day itself. “I followed Stav from morning until night with a small analog camera and direct flash,” Ofek says. “I felt like I was entering her world, seeing how she sees it. And it became a shared journey — not just photographer and subject, but sisters. When she had an eating disorder, I lived it too, from the side.”

The project quickly moved beyond the personal. It was published in a Jerusalem-based magazine, later in Haaretz, and eventually exhibited in Israel’s “Local Testimony” photography exhibition.

“I was nervous seeing my image displayed so large,” Stav says. “These weren’t stage photos at my peak condition. I was heavier, less defined. But I’m in such a healthy place now that I feel proud. I’m proud of the process.”

For both sisters, bodybuilding became a lens through which recovery could be explored without reducing the story to illness alone. “People think bodybuilding is shallow,” Stav says. “It’s not just putting on a bikini and showing your body on stage. It’s an intense mental game. The stage is 10 minutes. The journey is life-changing.”

Her journey now continues offstage, training others — including women who come to her because they know her story.

“I weighed 39 kilos at my lowest. Today I weigh nearly 55. I’ve never been this weight in my life,” she says. “Food is fuel now. A place to grow. And I’m happier than I’ve ever been.”

One photograph from “Miss Bikini” is currently on display at the “Local Testimony” exhibition at the Eretz Israel Museum in Tel Aviv, through January 31.