“Sorry, let me make sure I understood you correctly,” I ask Dr. Alona Barnea. “Are you really saying the IDF plans to create precise digital replicas of senior commanders that soldiers could consult at any moment, via chatbot?”

Barnea, head of the newly revealed neurotechnology department at MAFAT, the Defense Ministry’s Directorate of Defense Research and Development, does not hesitate.

“Yes,” she says. “The idea is to support decision-making using a digital twin. This is an AI system that thinks the same way a specific human expert would think. We are already collecting data and building digital decision-making profiles of individuals, including mapping their brain activity. There are early signs that it works, and this is something we are building over the next decade.”

A digital twin, for those unfamiliar with the term, is a detailed digital representation of an object, system, organ or process that can be operated on a computer as if it were real. Doctors use digital twins to simulate beating hearts before surgery. Aircraft manufacturers use them to run tests digitally rather than in the sky or wind tunnels.

“So I could ask a digital version of a regional commander for operational advice, and it would respond after ‘thinking’ the same way the real commander would?” I ask. “Is it even possible to replicate cognition?”

“In principle, yes,” Barnea says. “It requires extremely extensive data collection on brain activity across different situations. This allows us to build a framework that examines how the brain operates and how it could operate. These questions are crucial in intelligence work, in challenging assumptions and in understanding how different people interpret reality differently.”

Translating sound into sight

Until just weeks ago, Barnea’s name and even the existence of her department were classified. The reason becomes clear once you see what they are working on.

Barnea, 41, is an unusual figure within MAFAT, Israel’s civilian-military research body that produced Iron Dome, the Arrow missile and laser interceptors. A neuroscientist with international credentials, she previously worked as the right-hand assistant to Nobel laureate Prof. Paul Greengard at the Rockefeller University in New York.

Married to Nimrod, a venture capital investor at NFX, and a mother of two, Barnea returned to Israel during the COVID-19 pandemic as a returning scientist, planning to establish a stem cell research institute focused on incurable diseases.

Then the Defense Ministry called.

“I didn’t even know what MAFAT was at first,” she says. “They asked me to advise on a project combining biology and robotics within the Science and Technology Unit, which focuses on future battlefield challenges. I realized this was a place where ideas that sound like science fiction are explored deeply and systematically.”

Over time, she noticed that while many projects focused on human-machine interfaces, they approached them from the machine’s perspective.

“So we shifted focus to the human side,” she says. “Hybrid teams of humans and robots, brain-computer interfaces, and integrated intelligence that combines human and artificial cognition.”

4 View gallery

BrainsWay helmet using brain stimulation for the treatment of anxiety and depression

(Photo: BrainsWay)

Among the non-classified projects her team is pursuing are systems controlled solely by eye muscles, translating sound into visual information, silent speech using facial muscle electrodes, and hybrid human-AI decision-making teams.

Skeptics may question whether such delicate technology can work under fire.

“In the past, the focus was on vibration-based alerts,” Barnea explains. “But on the battlefield, adrenaline is so high that people may not even feel a bullet wound, let alone light vibration. So we are developing systems that reach the senses effectively, and we test them in real field conditions.”

The goal is intuitive systems that require no learning curve.

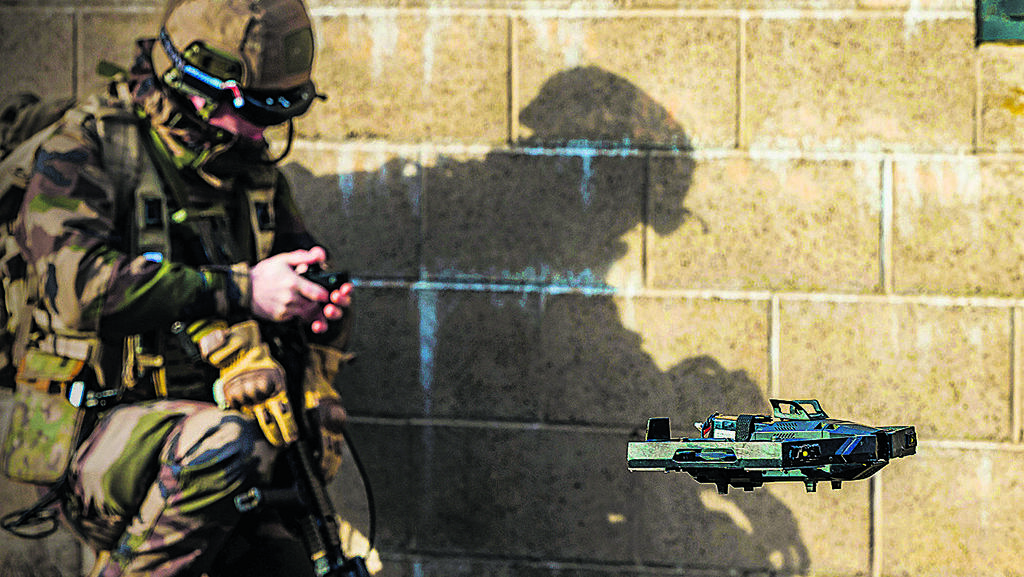

“A commander should not have to take their hands off a weapon just to issue a command or control a drone overhead,” she says. “It should work through eye movement, hand motion or even brain activity alone.”

And no, she insists, this is no longer science fiction.

“We know a lot about the motor cortex,” she explains. “When you move your hand, specific neurons fire. Even thinking about moving the hand activates those same neurons. The brain can easily learn to issue simple commands like left, right or forward.”

It does require training, she admits.

“A pilot does not fly an F-16 on day one either. We study how people learn to control their brain activity. It is possible.”

Seeing with sound

Another area her department explores is sensory substitution.

“Can people learn to ‘see’ with sound?” she asks. “Can we teach healthy individuals to process visual information through hearing?”

The project builds on research from Reichman University that developed a treatment for blindness known as the ‘musical eye,’ which converts visual space into sound. In Barnea’s work, sighted individuals are trained to process visual data through auditory cues.

Functional MRI scans show that over time, participants begin using visual regions of the brain to process sound.

“They literally see sound,” she says.

High risk, high failure, high impact

Barnea is candid about the failure rate.

“This is high-risk research,” she says. “We expect many failures. But when it works, the impact is long-term and dramatic.”

The strategy, she says, aligns with Defense Ministry Director-General Maj. Gen. (res.) Amir Baram’s emphasis on maintaining Israel’s technological edge.

Since October 7, her department’s mission expanded dramatically.

“We realized that much of what we develop for combat also applies to mental health, resilience and rehabilitation,” she says.

The result was a surge of joint projects with the IDF, Health and Science ministries, hospitals, universities and startups. The scale grew so large that it required a dedicated department.

This dual-use approach means that technology developed for battlefield drones can also power brain-controlled prosthetics.

Diagnosing the mind

One flagship effort focuses on objective mental health assessment.

“Unlike diabetes, we have no blood test for mental health,” Barnea says. “Diagnosis relies on subjective reporting.”

Her team is developing AI systems that analyze voice, facial expression, eye movement and physiological signals to assess stress, trauma and cognitive load.

One application is a pilot-assist system that detects fatigue or stress and redistributes tasks within the cockpit.

Another is an AI avatar that conducts psychiatric interviews, generating transcripts, summaries and treatment recommendations for clinicians. The system is already in use within the IDF’s rehabilitation and bereavement units.

“We are talking about diagnosis, not replacing human care,” Barnea stresses. “Responsibility and empathy remain human.”

Surprisingly, some patients reported opening up more to the avatar than to human clinicians.

“They said it was the kindest psychiatrist they ever met,” she says. “It wasn’t rushed.”

Humans stay in charge

Barnea also addresses fears about humanoid robots replacing soldiers.

“I do not believe that will happen anytime soon, certainly not in Israel,” she says.

She acknowledges the emotional complexity of working alongside human-like machines.

“When a robot walks next to you, you start developing feelings. That raises ethical questions.”

Still, she insists that humans remain central.

“In an increasingly autonomous battlefield, human judgment, values and context matter more, not less,” she says. “AI executes. Humans decide.”

Her guiding analogy is Waze.

“I usually follow it, because it is often right,” she says. “But when it is wrong, I ignore it. Responsibility always stays with the human.”

For Barnea, that principle is non-negotiable, even as technology pushes the boundaries of what was once imaginable.

“What sounded like science fiction five years ago,” she says, “is already in advanced trials.”