This is the story of Chaya Moshayev, 35, from Tel Aviv, a social worker, director at the Ma’avarim organization for the trans community and a screenwriter:

“When I was a year old, and we were living in the city of Kokand in Uzbekistan, my parents took me to a barber to shave my head. That was the custom there — boys and girls had their heads shaved at age one. I don’t remember anything, of course, but they say I was terrified. Shortly afterward, my hair began falling out all over my body — my head, my eyebrows, everything.

2 View gallery

Chaya Moshayev: 'My hair all over my body fell out at the age of one'

(Photo: Yuval Chen)

My parents didn’t understand what was wrong and took me to doctors. It was one of the reasons we immigrated to Israel, hoping to find a solution. In 1992, we arrived in Kiryat Gat — my parents and my father’s siblings, four families in one apartment, dealing with absorption challenges, the language barrier and everything that comes with it.

Only at age six did I receive the diagnosis: alopecia, an autoimmune disease in which the body identifies the hair follicle as a foreign object and attacks it. It usually appears after a traumatic event and rarely emerges at such a young age, as it did for me.

The diagnosis was difficult for my parents. They began a long journey that took us between doctors, rabbis, healers of all kinds, numerologists, celebrities with blessing ceremonies — all sorts of charlatans. When I think about the time and money they spent, it’s staggering.

When I was in kindergarten, they decided to put a wig on me. We drove to Jerusalem, to a salon that served ultra-Orthodox brides. They sat me on a big white chair and tried wigs on me that had nothing to do with a five-year-old girl. I went from being the bald girl to the girl with a wig costing thousands of shekels. It was uncomfortable, and I couldn’t manage with it.

At age nine, on rabbis’ advice, they even changed my name from Hana to Chaya. They never explained any of these experiences to me — what they were about to do, or that they planned to change my name.

One of the most vivid memories happened around age ten. A relative took us to an elderly woman in the Shapira neighborhood in Tel Aviv. I saw a box of pigeons on the table and didn’t understand. I had gotten used to being taken to older people who blessed me and performed rituals. But this woman grabbed a pigeon, decapitated it in front of me, took its blood and smeared it on my head. That is how I went home — with pigeon blood on my head.

I was a child who wanted to please, and I felt I had disappointed my parents by not having hair. And they, through everything they did, signaled they were trying to help me, to make me look like everyone else. Eventually, I understood that the world around me was more preoccupied with my hair loss than I was.

I struggled to fit in. I was sensitive, cried easily. Alopecia is tied to sensitivity; hair protects the skin, and without it, everything feels overwhelming. As a child, regulating that was hard. In my experience, adults loved me and looked out for me, teachers tried to support me, but there were school years when I barely communicated. I spoke only when spoken to.

When I was 14, my mother also developed alopecia. It marked the start of a period when I tried to help her, accompanied her to appointments, and she tried to cure the condition — for herself and for me. I didn’t understand her. After all these years without hair, I thought we should accept the situation.

My mother and I are very different, physically and in how we think. As a child, I created a story that I didn’t belong to the family, and once she developed alopecia, it became impossible to ignore that we share the same genes. Our relationship was complicated in those years. At first, I blamed her for passing on her genes. Later, it brought us closer.

At 15, I declared that I wouldn’t marry, and over time, I came out. After my national service, I began studying social work. At the end of the first year, two of my cousins — who are also close friends — convinced me to travel to India. When I bought the ticket, I told them I wouldn’t travel with the wig. One of them said, ‘So why are you wearing it here?’ I thought about it and realized she was right. That evening, I left the house for the first time without a wig. We went to a bar in Be'er Sheva and it felt amazing. I don’t know how to explain it, but I felt beautiful. I never focused much on makeup or appearance, and the wig was always external — a major point of dissonance for me.

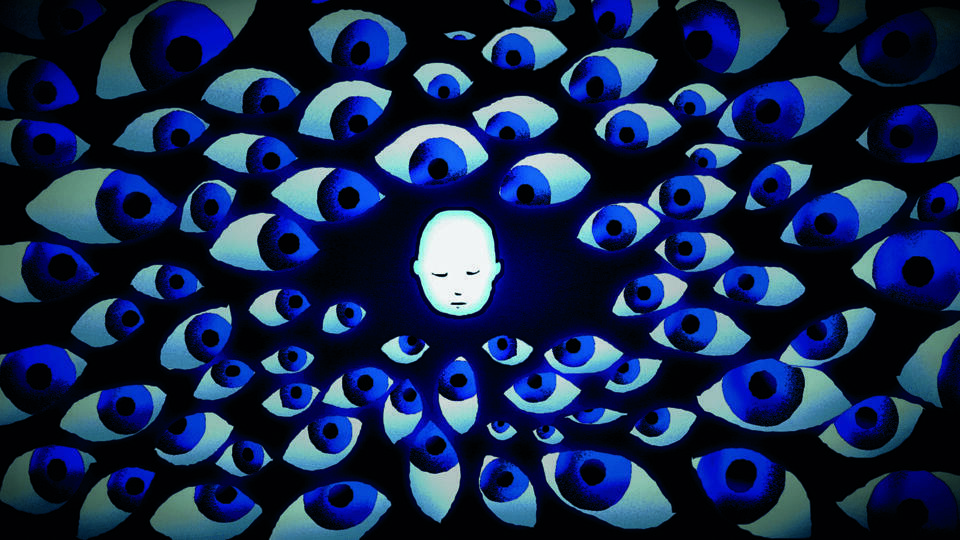

2 View gallery

From 'In Pigeon's Blood', the film by Chaya Moshayev and Hod Adler

(Illustration: Hod Adler)

Since then, I haven’t gone back to wigs. It requires me to constantly explain alopecia to every new person I meet. Often, I see frightened eyes. Some people think I’m ill, and the explanation reassures them.

After studying social work, I studied screenwriting at the Sam Spiegel Film School. Later, I learned that in Uzbekistan, my father and grandparents had worked at a movie theater. My first film, Puffs, was about two siblings from a traditional Bukharan family who come home to find their father dead — dressed in women’s clothing.

Recently, my second film, In Pigeon's Blood, was released. It’s a six-minute animated short telling the story of two women living with alopecia. I created it with the talented animator Hod Adler. The film screened at the Jerusalem Film Festival and is heading to festivals in Kyiv, Baku and Argentina.”

Bottom line: “Even though I grew up in a home that hid things and kept emotions inside, I try not to live that way. Today I share what’s happening in my life — emotionally and mentally — with my parents, hoping they will share back.”