Take a moment and look at the headlines from the past two years. The world is in the midst of one of the most accelerated, thrilling and turbulent periods in human history. Every day brings a new breakthrough: artificial intelligence reshaping how we think about creativity and work, chips powering thinking machines, green energy revolutions and the new space race.

Zoom out to the global innovation map and it looks like a loud, crowded party. On one side of the room stands the United States, the undisputed capitalist engine, churning out tech giants at breakneck speed. On the other side is China, with its sweeping technological ambitions and manufacturing power poised to upend the global order.

But if you listen closely, there's a deafening silence coming from the West. Where is Europe? Where is Europe’s Google? France’s OpenAI? Why doesn’t Germany have its own Tesla? How did the continent that gave the world the industrial revolution, the automobile and the printing press become irrelevant in shaping the future?

When fear wins out over boldness, you get the European story. This isn’t about a lack of talent—the engineers in Berlin, physicists in Paris and developers in Stockholm are among the best in the world. This is a tale of deliberate cultural and political choices. In recent decades, Europe has shifted from a continent of entrepreneurs to a continent of regulators.

This article is more than just economic analysis. It’s a journey into the decline of an empire. We’ll dive into the data showing how overregulation is choking innovation, explore why capital is fleeing to the U.S. and examine how Europe went from leading the world to becoming the most beautiful museum in history—a decorative relic.

State of play: anatomy of a vanishing act

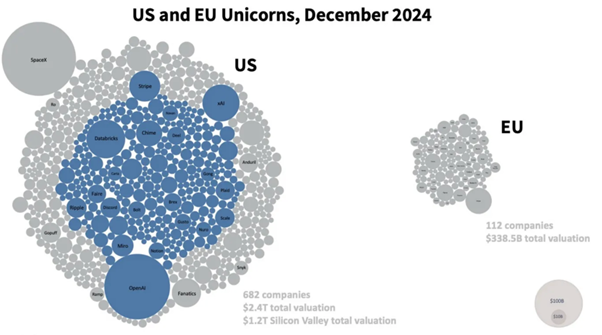

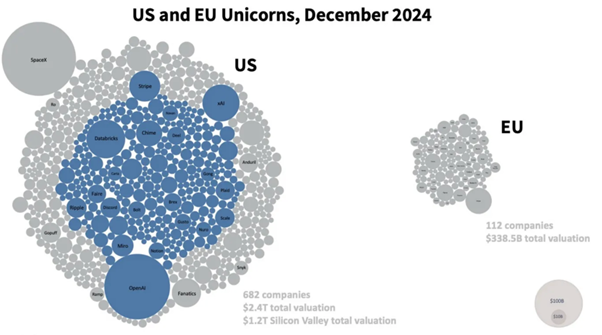

To understand why the global investment portfolio is overwhelmingly tilted toward the United States, you don’t need central bank speeches—you just need to look at the chart in front of you. The visual gap tells the whole story.

The massive block on the left represents the U.S., with a total of $2.4 trillion in unicorns—privately held companies valued at $1 billion or more, the startups reshaping the future. At the heart of this block is a dense blue core: companies born exclusively in Silicon Valley. The astonishing fact is that these blue bubbles alone are worth $1.2 trillion, nearly four times the combined value of all European unicorns, represented by the small, gray, compressed cluster on the right.

4 View gallery

Unicorns in the United States and the Europran Union

(Illustration: CB Insights 2024 Unicorn list)

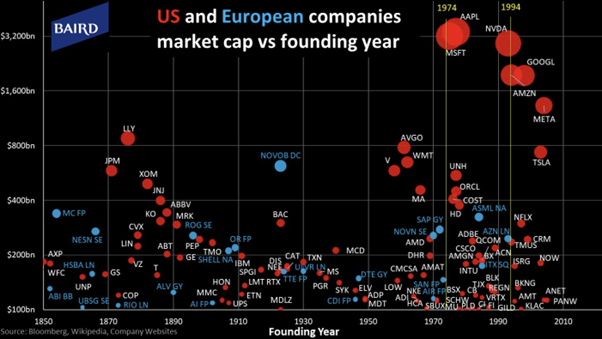

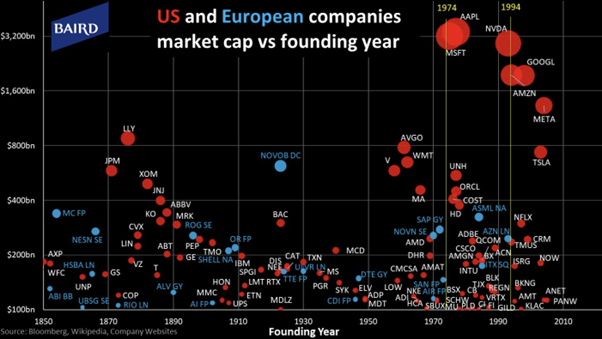

But the most alarming figure isn't the current state of Europe’s startup ecosystem; it's the long-term structural failure that led here. In the past 50 years, the European Union has not produced a single homegrown company that scaled from scratch to a market cap of over $100 billion. To grasp the full extent of the hole Europe has dug for itself, look at the next chart, which maps the world’s largest companies by founding year.

Focus on the right side of the graph, covering the digital era from the 1990s onward. This section is completely dominated by giant red bubbles—U.S. companies that built the digital age we live in today: Google (GOOG), Amazon (AMZN), Meta (META), Tesla (TSLA) and Nvidia (NVDA).

4 View gallery

In the past 50 years, the European Union has not produced a single homegrown company that scaled from scratch to a market cap of over $100 billion

(Illustration: Bloomberg, Wikipedia, Company Websites)

And where are Europe’s blue bubbles? They’ve vanished. Nearly all of Europe’s major firms were founded in the 19th or early 20th century, concentrated in the bottom-left quadrant of the chart. The continent is still coasting on legacy success in pharma, automotive and traditional industry.

While the U.S. has birthed multi-trillion-dollar tech titans in just two decades, Europe has failed to produce even a single breakout player in this arena. The chart is a stark reminder: Europe missed not only the internet revolution, but also the mobile wave, the cloud era and now the AI boom.

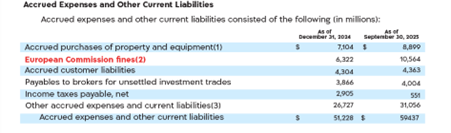

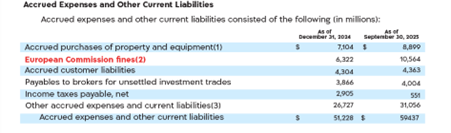

Fines outpace taxes

When value creation stalls, revenue has to come from somewhere else. And Europe has found an alternative: extracting value from others. The 2024 numbers paint a surreal but telling picture of the continent’s economic model.

4 View gallery

A line item in the profit and loss statement dedicated to EU fines

(Illustration: Alphabet Investor Relations)

In 2024, the European Union collected €3.8 billion in fines from U.S. tech giants, compared to just €3.2 billion in total income tax paid by all publicly traded European tech companies combined.

That gap lays bare Europe’s new financial dependency. Instead of cultivating its own high-growth firms to generate tax revenue through innovation and profits, the continent has become reliant on penalizing successful foreign players. If Europe can’t beat Google or Meta at the innovation game, it’ll charge them bureaucratic “usage fees” instead.

A tired work culture

Beyond the chokehold of overregulation lies something deeper: work culture. While the U.S. and much of East Asia embrace a grind mindset, celebrating hustle, ambition and 24/7 availability, Europe elevates “free time” as a cultural ideal. This isn’t just a matter of personal preference; it’s a legal and social norm. In France, for example, calling an employee or colleague at 5:01 p.m. borders on sacrilege. It’s seen as profoundly disrespectful.

In an environment where lifestyle consistently takes precedence over output, it’s nearly impossible to keep pace with Silicon Valley’s relentless tempo or the factory floors of China, where office lights are still burning at 2 a.m.

The 'Europe tax'

For American tech giants, EU fines have gone from rare setbacks to standard operating expense. In Google’s financial reports, penalties from the European Commission are no longer buried in the footnotes—they’ve earned their own dedicated line item on the P&L: a fixed expense under the heading “European Commission Fines,” right alongside utilities, servers and payroll.

When a company the size of Google budgets billions as a recurring line item, markets get the message: Europe is no longer a competitive player on the field. It’s the referee, charging hefty admission fees just to let others play on its turf.

The Apple case: punishment as policy

The clearest example of Europe’s current strategy is the astronomical €1.84 billion fine levied against Apple this past March. The official reason: anti-competitive behavior in the music streaming market, following a complaint by Spotify.

But the fine print reveals the deeper issue. The actual “damage” Apple was accused of causing was valued at roughly €40 million, a figure the EU’s competition commissioner herself likened to a parking ticket for a company of Apple’s size.

To “teach Apple a lesson,” the EU arbitrarily tacked on another €1.8 billion as a “deterrent.” That, in a nutshell, is the problem: rather than building the next Spotify (SPOT) through investment and innovation, Europe is protecting the last one by slapping massive penalties on outside competitors. It may be a legal and financial win in the short term, but it's an economic own goal in the long run.

Why did Europe fall out of the game?

If fines are the end product, the root causes run much deeper. Europe’s stagnation isn't bad luck; it’s the result of four structural anchors dragging the continent down and holding it back from competing with the U.S. and China.

The energy shock

For decades, Europe—especially Germany—built its industrial model on one core assumption: cheap Russian gas. That assumption shattered in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine, pipelines were shut off and prices spiked.

The fallout has been catastrophic. European firms now pay 2–3 times more for electricity and 4–5 times more for natural gas compared to their American counterparts. You can’t build a competitive AI ecosystem—reliant on power-hungry server farms—or maintain heavy industry when your energy costs are triple the global standard.

The demographic bomb

While the U.S. enjoys relatively healthy demographics, Europe is aging rapidly. The numbers are stark: by 2040, Europe’s workforce is projected to shrink by around 2 million people annually. Fewer workers and fewer young minds for innovation means a shrinking tax base, which must shoulder the growing cost of pensions and welfare for an aging population. It’s a vicious economic cycle.

Low productivity

A direct outcome of Europe’s innovation deficit is low productivity. Roughly 70% of the GDP-per-capita gap between Europe and the U.S. comes down to this: European workers produce less economic value per hour. Why? Because the tech isn’t there. Without local software and AI giants streamlining workflows and driving efficiency, Europe falls further behind.

Defense dependency

Europe’s economy was built on the assumption that the U.S.—through NATO—would always provide military cover. But the war in Ukraine and shifting political winds in Washington have shattered that illusion.

Now, Europe is being forced to divert hundreds of billions toward defense, a budget that could have gone to innovation and growth. The continent finds itself exposed, expensive to protect and lacking a unified, competitive defense industry of its own.

Where is the innovation?

The cultural and economic gap is glaring when comparing the top of the American market to that of Europe. While Wall Street is led by the “Magnificent 7”—tech giants like Nvidia (NVDA), Microsoft (MSFT) and Amazon (AMZN) that are redefining the boundaries of human capability—Europe’s leading indexes are dominated by companies that feel frozen in time.

The continent’s largest corporations—luxury empire LVMH, food giant Nestlé (NSRGY) and pharma heavyweight Novo Nordisk (NVO)—are overwhelmingly tied to the old economy. Europe may excel at selling handbags, pharmaceuticals and chocolate, but it’s missing entirely from the playing field where the future is being built. There is no European Google (GOOG), no European Nvidia, and under current conditions, the odds of one emerging are close to zero.

The tragedy isn’t a lack of talent or brilliance—it’s Europe’s inability to retain it. The data is clear: European founders who achieve technological breakthroughs are packing their bags and heading to the U.S. early on. They’re fleeing suffocating bureaucracy, punishing tax regimes and limited access to capital for the American ecosystem that enables rapid scaling.

The result is a steady brain drain. The most promising startups born in Paris, Berlin or Stockholm ultimately morph into American companies for all intents and purposes, leaving Europe as an incubator of ideas and profits for others.

The best example is Spotify, arguably Europe’s biggest tech success story of the past decade. Despite its headquarters remaining in Stockholm, when Spotify decided to go public, it skipped European exchanges entirely and headed straight for the New York Stock Exchange.

A grim outlook and the value trap

Is there a bright spot on the horizon? As of now, not really. There are glimmers of hope in sectors like defense—a standout being THEON, a drone company trading at an operating earnings multiple of 21, below market average.

But when the average investor scans European markets and sees low multiples, the instinct is to think: “It’s cheap.” In reality, it’s the textbook definition of a value trap. The stocks are cheap because there’s no growth. And there’s no growth because the engines have stalled.

Europe stands at a historic crossroads, and it’s currently choosing the wrong path. It’s prioritizing regulation over production, fines over innovation and preserving the past over building the future. Without a radical pivot, the continent is on track to end the next decade with a new and unfortunate identity: the world’s most beautiful museum. A lovely place to visit on vacation, but the last place you’d want to invest in building tomorrow.

The bottom line for investors

Given the bleak outlook, many investors’ gut reaction is to steer clear of Europe entirely. And indeed, European indices continue to trade at a significant discount to their U.S. counterparts, with markedly lower earnings multiples. But as we’ve seen, this discount is often a textbook “value trap”—stocks are cheap because growth has stalled.

Still, within the broader stagnation, there are opportunities for discerning investors who know how to be selective.

The key is extreme selectivity. Instead of buying the index (like the DAX or CAC), investors can focus on specific niches that benefit from the very structural shifts we’ve outlined:

Defense: This may be the most compelling growth story on the continent. As Europe is forced to rearm in the wake of a receding American security umbrella and mounting threats from Russia, European defense firms are seeing record order books. Governments have no choice but to open their wallets. It’s a sector driven by existential necessity.

Pharma and healthcare: With a collapsing demographic curve and an aging population, demand for medical care and pharmaceuticals is only accelerating. Giants like Novo Nordisk have shown that even from a small country like Denmark, it’s possible to conquer global markets, especially when your product is essential and not beholden to stifling digital regulation.

The lone diamonds: Some European companies have managed to become global juggernauts despite their local environment. The standout example is ASML (ASML) of the Netherlands, which holds a global monopoly on the machines needed to manufacture the world’s most advanced semiconductors.

Without ASML, there’s no Nvidia, and no AI. But even ASML, for all its strengths, is a big fish in a shrinking pond. The company recently crossed the $500 billion market cap milestone, an extraordinary feat that makes it just the third European firm ever to reach that level. And yet, across the Atlantic, Nvidia is nine times larger. The disparity is so vast that on a volatile trading day, Nvidia can gain or lose the equivalent of ASML’s entire market cap, built over decades of painstaking work.

For investors seeking high-growth tech and next-gen innovation, the clear destinations remain the U.S. and China.

Europe, by contrast, has become something else: a good place to find stable, undervalued traditional companies or sectors poised to benefit from crisis. But it is no longer the place to look for the next big thing.

Guy Natan is CEO and founder of Guy Natan Ltd., managing partner at Valley Hedge Fund and a financial columnist for ynet Capital, B’Sheva newspaper and the Sponsor website. He is also the host of the “Heat Map” podcast, a weekly panelist on Channel 10’s economics program “Tel Aviv–New York,” and a regular guest on Channel 13’s “The Day That Was.”

Yedioth Communication Ltd., Ynet, and Mivraka Communications Solutions Ltd. have no affiliation with this content and no financial or editorial interest in it. The content does not constitute investment advice or a substitute for professional consultation tailored to an individual’s specific needs. It should not be regarded as factual or exhaustive information, and readers should not rely on it as such.