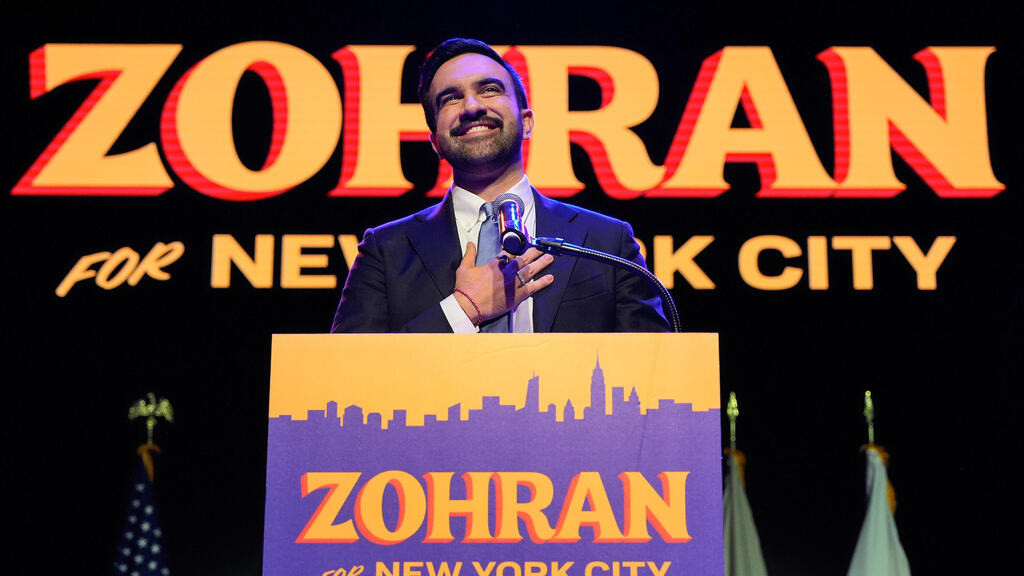

When will Jews understand that the Land of Israel is their place? At a time when we hear about Israelis considering moves to Europe or North America, the question becomes even sharper: what would convince them to change their minds? Do they need a sign from heaven? Would the election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor of New York signal to the city’s Jewish residents that it is time to pack their bags and return to the Promised Land?

This week’s Torah portion, Vayetze, touches this question directly. Jacob flees his family and homeland because his brother Esau wants to kill him. He arrives in Haran, marries Rachel and Leah, the daughters of his uncle Laban, and builds a strong family. After 20 years of work he finally receives wages. Life appears comfortable and hopeful. Jacob shows no sign of wanting to leave.

In fact, he is not meant to leave yet. Rebecca told him she would call him back once she knew that Esau had let go of his anger. She has not sent any message and Jacob has not asked. Life in Haran continues as usual. Time passes quickly when one enjoys stability. Yet just when everything seems to fall into place, familiar strains of antisemitism return, the same attitudes seen earlier in the stories of Abimelech and Pharaoh. This is a sickness that crosses borders and continents and does not depend on geography.

Jacob’s brothers-in-law know how hard he has worked for many years. Instead of appreciating his modest success, they speak loudly enough for Jacob to hear that he has taken what belonged to their father and that his prosperity came at Laban’s expense. In other words, they repeat a claim many nations have made throughout history: the Jews profit at our cost.

Laban, who once praised Jacob and credited him for bringing blessing to his home, no longer treats him with the same warmth. Jacob struggles to meet with him. At times Laban openly favors Jacob’s rivals.

Even this is not enough to push Jacob to act. Then he receives a clear divine message: return to the land of your fathers and to your birthplace. This command should be decisive. Jacob gathers his wives and begins a long explanation of why he must return to Israel. He describes their father’s changed attitude. He explains that God told him to go back. He recounts his years of labor, Laban’s attempts to cheat him and the protection he received, and again describes the angel who instructed him to return.

This raises a significant question. If God has given a clear command to return, why does Jacob feel the need for further arguments? And why must so many events accumulate, from the brothers-in-law to Laban to the divine message? Should one sign not be enough?

Some commentators teach that the portion reveals how hard it is for a person to leave a familiar environment. It is difficult to wake up one morning and say that after decades in one place the signs now show the situation will not end well. There is no need to wait for another 1939. The signs were visible in 1936 and 1938 as well. Yet people tend to believe, as Meir Ariel put it, that if we survived Pharaoh we will survive this too. Even when warning signs multiply, people often need an unmistakable command before they act.

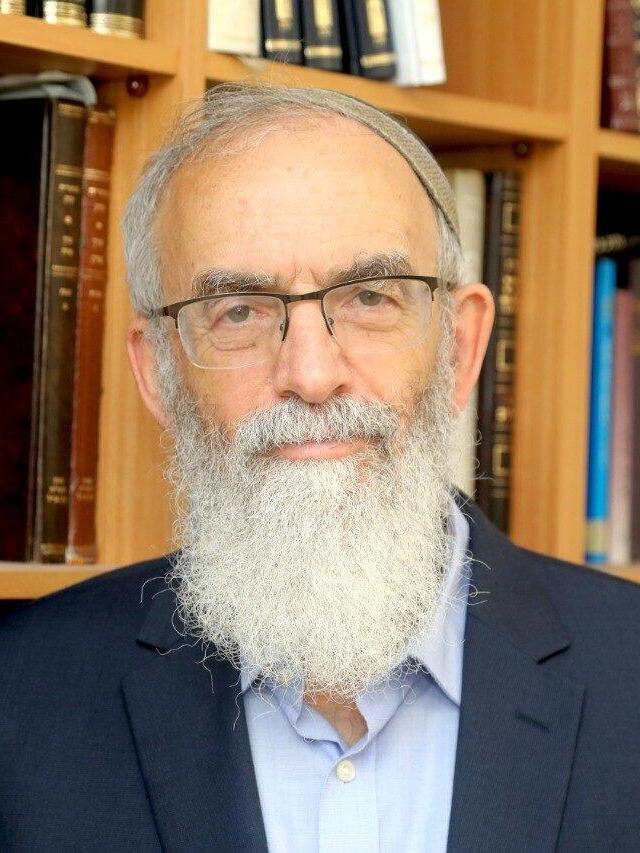

Rabbi David Stav

Rabbi David StavSince childhood, however, I have heard another interpretation. This view holds that the events Jacob described and the divine message were not separate but part of the same process. God spoke to Jacob through the political and social events around him. When Jacob tells his wives that God instructed him to return and then mentions their father’s changed attitude, he is showing them how he understands God’s guidance.

Jacob does not know whether Esau will be waiting for him in Israel. Later we learn that Esau is approaching with 400 men. None of this matters. Jacob cannot remain in Haran. In a place where a Jew must hide his identity out of fear, and in a place where prominent leaders hold openly or quietly antisemitic views, no additional signs are needed. Not in England, not in the Netherlands, not in France. This is how God speaks to us.

Does this mean Israel has no dangers? Certainly not. We face them daily. The descendants of Esau and Ishmael still stand at the doorstep. But this is our land, our place and our identity. In foreign lands Jews cannot fully belong as a people with a distinct identity.