The U.S. effort to exhaust negotiations with Iran has been driven in part by pressure from the Gulf states, Iran’s closest neighbors, which view a regional military confrontation as a direct threat to their security, infrastructure and economies.

At first glance, it might have been expected that Gulf states would push Washington toward military action against Iran, their primary strategic rival. Instead, they have largely avoided public statements, adopted a neutral posture and worked intensively behind the scenes to mediate between Washington and Tehran in an effort to prevent escalation.

1 View gallery

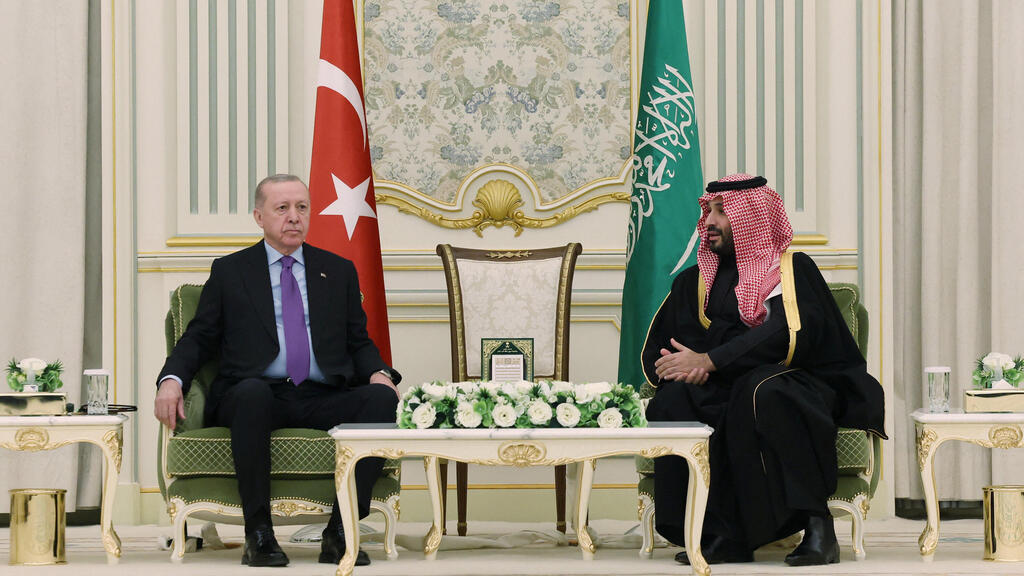

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh

(Photo: Murat Cetinmuhurdar/Turkish Presidential Press Office/Handout via Reuters)

For the Gulf states, the most immediate danger is an Iranian response directed at their territory. Energy infrastructure, desalination facilities, ports and, above all, U.S. military bases hosted on their soil would likely be prime targets. Memories remain fresh of the 2019 Iranian attack on Saudi Arabia’s Aramco facilities, Houthi missile fire at the United Arab Emirates in 2022 and Iran’s symbolic strike on the Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar in June 2025. This time, Gulf officials fear, the response could be far more severe.

At the same time, Gulf capitals are also anxious about what they describe as a U.S. strike that would be “too successful,” one that could lead to the rapid collapse of Iran’s Islamic Republic, now seen as historically weakened. From their perspective, the fall of the regime would not necessarily usher in stability, but rather chaos: internal power struggles, institutional collapse, the rise of extremist actors, refugee flows and, most critically, the loss of a clear address for managing crises.

Iran, despite its hostility, is a known quantity. Its patterns of behavior, red lines and internal constraints are familiar. For the Gulf states, the devil they know is preferable to prolonged instability.

This calculus underpins the current Gulf approach: mediation, neutrality and détente. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Oman are working to calm Washington, not out of identification with Tehran but out of a sober assessment that the risks outweigh the potential gains. At the same time, they are signaling to Iran that they will not allow their territory to be used as a launchpad for an attack and are seeking to reduce the likelihood that the Gulf becomes a theater for retaliation.

The détente is not based on illusions about the nature of the Iranian regime, but on an acknowledgment of power gaps and the Gulf states’ own vulnerabilities. Presenting themselves as actors trying to prevent a strike is also seen as a way to reduce the chances of an Iranian response against them.

Gulf leaders hope for a change in Iran’s behavior rather than the overthrow of its regime. They fear a strong, revolutionary Iran, but they also fear a rapidly collapsing one. From their perspective, a weakened, restrained and functioning Iran is preferable to a wounded, enraged and unpredictable state.

Dr. Yoel GuzanskyPhoto: INSS

Dr. Yoel GuzanskyPhoto: INSSThe best way to achieve that outcome, they argue, is through an agreement that curbs Iran’s nuclear program and, in particular, its missile development. Gulf officials frequently note that, unlike Israel, they face threats from Iran’s short-range missiles and lack Israel’s advanced missile defense systems.

Externally, this policy diverges sharply from Israel’s, which continues to push for decisive military action against Iran. Gulf states also remain uncertain about President Donald Trump’s ultimate intentions. Had they been convinced he was prepared to go all the way and topple the Iranian regime, their calculations might have been different.

Instead, they are pressing to give negotiations a chance, while buying time to strengthen their own defensive capabilities.

Dr. Yoel Guzansky is a senior researcher on Gulf affairs at the Institute for National Security Studies and a former official at Israel’s National Security Council