During a recent visit to the renewed and beautiful Shiloh Winery, I heard from the owner about a visit he made to a colleague in the Upper Galilee, and how stunned he was to see that the northern farm had turned into a fortified compound, complete with high fences, cameras and floodlights.

His son, home for a 48-hour leave from Gaza, was standing night watch—because there's no other choice. This stands in stark contrast to the past, when everything was so open that people would leave the keys in their farming equipment’s ignition in case a neighbor needed it.

What changed? Protection money. Gangs, most of them Arab, are making life miserable for business owners who refuse to go along and pay extortion fees. Those of us who’ve been around long enough remember a time when you could go hiking, leave your car behind and walk to a spring without fearing it would be stolen or broken into. There was a time you could pitch a tent in nature and sleep in peace.

But for many years now, personal security in Israel has faded. Cars are stolen, Arab gangs engage in shootouts in broad daylight, the area is saturated with weapons—and that’s just on the criminal side, not to mention the terrorism that leads people to walk around Tel Aviv with handguns.

Shiloh Winery buys most of its grapes from farms in Samaria that grow some of the finest wine grapes in the world. These farms are unfenced, and the low fences surrounding the vineyards are meant to keep out deer herds and other animals. From time to time, you might see a girl, even just 14, walking confidently through the area with a flock of sheep—in a region where no one’s even heard of protection money.

What’s going on here? Is this even in Israel? Is this the Israel of fences and walls? Well, this safe bubble is just a few miles from Nablus, and not far from the terror black hole created by the “disengagement” in northern Samaria—an area that has become the West Bank’s terror hub, a twin to the monster that is Gaza.

This reality is not the result of a sudden upgrade in police and army capabilities. It was shaped by the idealistic population living there, determined to hold on to the Land of Israel without fear—what some call “hilltop youth,” though most of them are not youth at all but families who have established farms in remote areas.

Most moved there with full coordination from the IDF, settling on state land that was on the verge of being taken over by a coalition that includes the Palestinian Authority, far-left hate groups, foreign anarchists and Bedouins—with massive involvement and funding from the European Union.

A family that moves to a new farm knows full well that they will live in danger and won’t get much sleep at night, because someone has to keep watch. The modest farm is not economically viable, at least not in the early years, and in most cases, one of the adults has to work outside the farm to make a living. Their only real advantage is knowing they are protecting a piece of the homeland from falling into enemy hands, because through grazing, they can control thousands of acres.

Anarchist visits

Some of the farms receive visits from anarchists who drive herds onto their land, sabotage equipment, support Arab harassment, spread lies and libels and even assault the shepherds. As soon as a new farm is established, it becomes the front line, and the previous farm behind it becomes a rear, safer position—gradually expanding the overall area of safety.

The Fayyad Plan aims at surrounding Jewish communities, IDF bases and main roads with Arab settlement, in order to sever them in the future. The response to this plan is the farms. This is the real game: a struggle over every acre—and in truth, over existence itself.

When the Labor movement’s pioneering settlements did the same at the beginning of the last century, they were rightly celebrated in songs and praised across the political spectrum. But today’s pioneers look a bit different—they wear kippahs and have long curled sidelocks, and for that reason, they’ve been vilified in parts of the media, even though they invented nothing and are simply repeating the methods of their predecessors from Mapai and Hashomer Hatzair.

The Bedouin encampments understood very clearly who they were dealing with. Sent by the Palestinian Authority and funded by the European Union, these encampments were established to seize Area C—territory under full Israeli control—under the “Fayyad Plan.” This is a strategic program aimed at surrounding Jewish communities, IDF bases and main roads with Arab settlement, in order to sever them in the future.

The response to this plan is the farms. And when a new farm is established, the Bedouins quickly grasp the reality and move elsewhere. This is the real game: a struggle over every acre—and in truth, over existence itself. All the well-funded campaigns are aimed at fighting and thwarting this rescue effort, in order to salvage the failing Palestinian state project.

For example, during Sukkot 2023, a new farm was founded. By Simchat Torah, the war had already broken out. The husband, a reservist company commander in the Paratroopers, rushed to the fighting in Kfar Aza near the Gaza border. The wife remained at the farm with three small children, a few teenage boys and some security personnel. They lived in tents through the winter mud, fending off assault attempts from Arabs in a nearby village. Five months later, the husband returned from reserve duty to find a farm well into its development, built by the teens who lived there.

This farm alone safeguards 2,500 acres adjacent to Rosh Ha’ayin, a region once overrun by intentional and strategic land takeovers along the Green Line, east of the security barrier. Shortly after it was established, antiquities theft at a nearby archaeological site ceased. The trash fires that had choked residents inside the Green Line stopped. The illegal land grabs ended, and the area returned to serving as IDF training grounds—after the army had previously given up and withdrawn.

Much of the burden on the IDF has simply disappeared

In another case, a farmer in the northern Jordan Valley passed away, and there were concerns that the nearby village—known as a protection-racket stronghold—would seize the land. The area is notoriously tough, so a farmer from Samaria was approached and accepted the challenge, placing a suitable family there. Within weeks, they were greeted with bursts of gunfire whistling past them, but they did not back down. Today, the farm is thriving, and the land remains in Jewish hands.

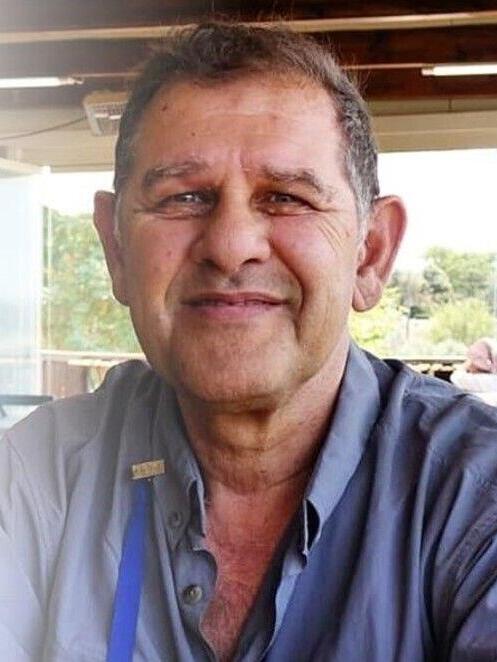

Boaz Haetzni Photo: Forestrain

Boaz Haetzni Photo: ForestrainThe IDF, for its part, has noticed that farms translate into security. Much of the burden of missions that had been placed on the military has simply disappeared in areas where such farms were established. Drivers on Judea and Samaria roads, who had grown accustomed to anxiously scanning areas from which they were often pelted with rocks, now see Israeli flags waving. Stone-throwing incidents have declined, as have land seizures and severe environmental damage. In many cases, it turns out to be more efficient and cost-effective to assign a few soldiers to protect a farm that, in turn, secures a vast area.

“The New Anarchists,” screamed newspaper headlines last week, describing serious allegations of attacks on Arabs, soldiers and even fellow settlers by a violent fringe group known as “hilltop barbarians.” How many people are we talking about? By my estimate, a few dozen. Even if the number is higher, the law enforcement authorities ought to start doing their job and address the issue—for everyone’s sake. Otherwise, one might begin to suspect that someone prefers to let them run wild in order to smear the vast majority of extraordinary pioneering farmers settling the land.

And if we’re cracking down on anarchists, it wouldn’t hurt to start taking seriously those on the left who come into the area, incite tensions and receive almost no attention from the media or the law.