We are told to fear an "axis of evil," a united front of rogue states marching in lockstep. But after the smoke has cleared from the recent "12-Day War," we are not looking at a united front at all. We are looking at the wreckage of a profoundly fragile partnership built on desperation and transactional gain.

The pact between Iran and North Korea was never forged in stability; it was an alliance between a cornered customer and a seller with nothing to lose. The war has exposed this truth for all to see.

That instability, laid bare by Iran's battlefield humiliation, is precisely what should keep us up at night.

The conflict starkly revealed the critical difference between the two regimes: North Korea possesses a mature and tested nuclear arsenal, while Iran does not. Pyongyang’s nuclear program provides Kim Jong Un a powerful deterrent against direct attack—a security guarantee Tehran can only envy. Iran, despite its aggressive rhetoric, was shown to have conventional forces that were vulnerable. This power imbalance fundamentally reframes the relationship. Iran is no longer just a partner; it is a dependent client, and its desperation has only deepened.

Now, watch how the great powers react. As the gears of a wider global conflict begin to grind, Russia and China are making a strategic shift. They are shifting their strategic weight away from the weakened Iran and toward the more formidable North Korea.

Russia's need for battlefield munitions has made Pyongyang an indispensable military depot, elevating their relationship to a "Comprehensive Strategic Partnership" with a mutual defense clause—a commitment far stronger than any offered to Tehran.

3 View gallery

Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un sign Comprehensive Strategic Partnership agreement

(Photo: Kristina Kormilitsyna, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, File)

China, ever the pragmatist, sees a nuclear-armed North Korea as a complicated but permanent buffer. Iran, however, is now viewed as a volatile actor that could drag Beijing into a Middle Eastern quagmire. For Beijing, which prioritizes stability, a weakened and reckless Iran is a liability.

At its heart, this relationship was destined to collapse. Two autocrats like Ali Khamenei and Kim Jong-un, who both desire to be king of their respective hills, do not make for lasting allies. They make for rivals in waiting. Their personal ambitions were always on a collision course, and the 12-Day War has slammed the accelerator.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Herein lies the true danger. As Alexey Likhachev, head of Russia's state nuclear corporation, Rosatom, recently warned, "A very dangerous line has been crossed... there are a few steps left before catastrophic decisions are made." The real threat is not a grand, coordinated war. It is the "black swan"—the one catastrophic mistake no one sees coming.

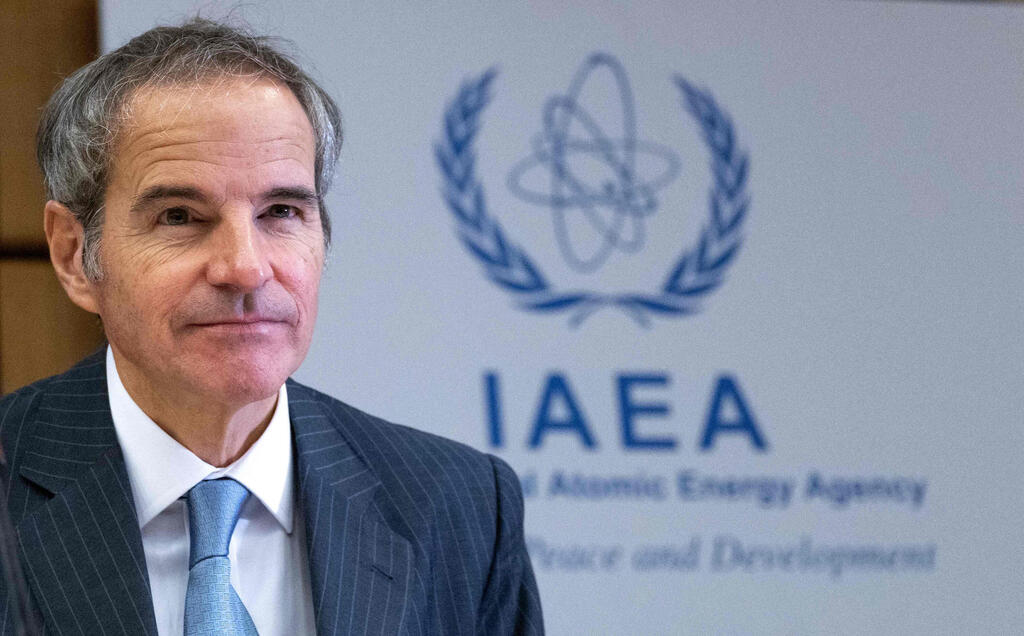

The destiny of the region may not be sealed by a deliberate act of war, but by a desperate miscalculation leading to what IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi warns could be a "Massive radioactive release similar to the 1986 Chernobyl disaster."

A regional war will not be ignited by a master plan. It will be sparked by the chaos of a global conflict that pushes a desperate regime too far. The flashpoint won't be a declaration of war, but the horrifying, uncontrolled fallout from a nuclear disaster at a facility like Bushehr. It would be a crisis that poisons the land and forces the world to react, with no clear aggressor and no simple solution.

When this house of cards finishes its collapse, the consequences won't be contained. They will land right on our doorstep, carried on the wind. We aren't facing a united front. We are facing a tumultuous pact where the final act isn't a strategic transaction, but a regional nightmare. The first step to protecting ourselves is to see the danger for what it is. The real threat isn't their alliance; it's the certainty that it will end in a catastrophe of their own making.

- Jeshurun Hight is an academic intern at the Moshe Dayan Center and a graduate student in government at Reichman University; he studied diplomacy at the University of Oxford.