Frank O. Gehry, the award-winning architect whose work helped redefine contemporary design, has died at 96. Gehry, a Canadian-born Jewish American regarded as one of the most original and striking talents in the history of American architecture, died Friday at his home in Santa Monica, California. Meghan Lloyd, his chief of staff, confirmed the death, which followed a respiratory illness.

Gehry’s most widely celebrated popular success, and the building for which he will be remembered more than any other, is the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. Clad in titanium, the museum sits in an industrial city in northern Spain and became an international sensation when it opened in 1997. Its arrival helped spark the city’s revival and made Gehry the best known American architect since Frank Lloyd Wright. The building’s exuberant look, a composition of shimmering silver forms that seem to burst from the ground, signaled the rise of an emotionally charged architectural style. In Israel, he was involved in the planning of the Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem.

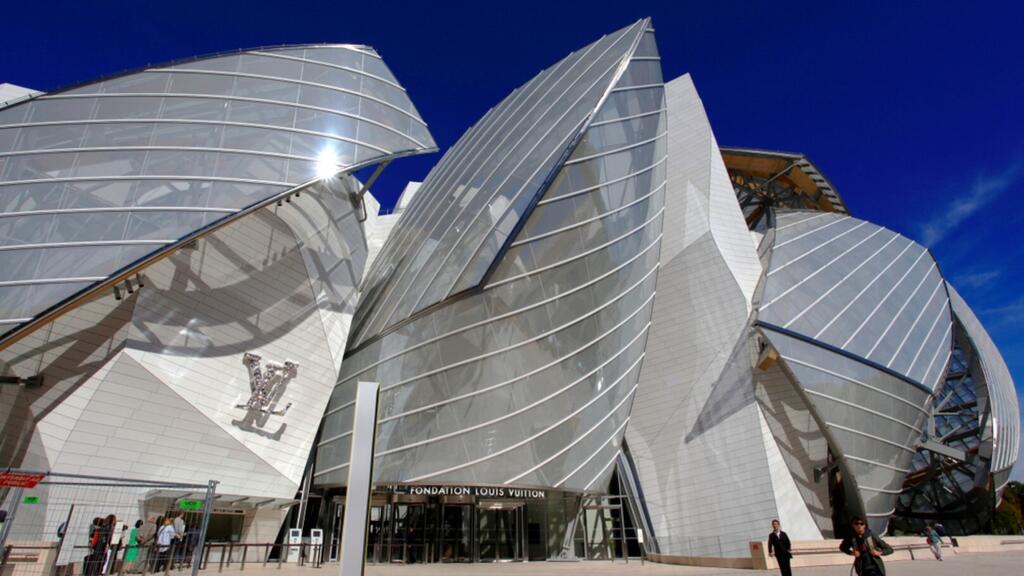

Among the first architects to grasp the liberating potential of computer-aided design, Gehry went on to create a string of critically acclaimed buildings, many widely considered masterpieces. Their sculptural boldness and visual force rivaled, and in some cases surpassed, the baroque architecture of the 17th century. Other notable works include the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles (2003), the New World Center in Miami (2011) and the Louis Vuitton Foundation museum in Paris (2014), which looks as if it were made of blown glass. Gehry received the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1989, but his reputation was established earlier.

In 1978, he completed the renovation of his Santa Monica home, a simple wooden cottage transformed into a fierce visual statement through cladding of timber beams, corrugated metal and chain-link fencing. Its raw, almost violent form reflected the political and generational rifts in American society since the 1960s and placed Gehry at the forefront of architectural debate. Over the following years, he designed additional houses with the rough aesthetic of structures that appear to be still under construction. Philip Johnson, one of America’s leading architects, said in 1982, “It is neither beauty nor ugliness, but a strange sense of satisfaction unlike any other space.”

Gehry explained in a 2012 interview that he rebelled against the architectural conventions of the period, including the modernist house associated with Mies van der Rohe. “I couldn’t live in a house like that,” he said. “I’d have to clean my clothes, hang them properly. It was pretentious. It didn’t feel like life.”

Over time, Gehry expanded his repertoire into even more sculptural designs, including the Vitra Design Museum in Germany (1989) and the Dancing House in Prague (1996), nicknamed “Ginger and Fred” after the American dance duo. Some viewed his work as closer to sculpture than architecture. Others argued it represented a global culture that turned architecture into a brand. Gehry, sometimes labeled a “starchitect,” sparked debate, but the emotional power of his buildings was seen as reviving architectural spirit after decades of dry functionalism and postmodern clichés.

A childhood among tools and materials

Gehry was born Frank (Ephraim) Owen Goldberg on February 28, 1929, in a middle-class neighborhood of Toronto. His father worked in a grocery store and sold pinball machines, and his mother was a homemaker. As a child, he worked in his grandfather’s hardware store, where he developed a fondness for everyday materials. His grandmother brought home a live carp from the market once a week, an experience that stirred images of fish that would return again and again in his work.

In the 1940s, the family moved to Los Angeles because of his father’s health problems. After short military service, Gehry enrolled at the University of Southern California. He initially studied ceramics but switched to architecture after being exposed to the work of architect Raphael Soriano. Around that time he changed his last name to Gehry in an effort to avoid antisemitism.

He opened his own firm in 1962. Early in his career he designed office buildings and stores for developers, but he drew inspiration from local Los Angeles artists who lived and worked in industrial structures. He sought to bring the openness and freedom of that artistic environment into architecture.

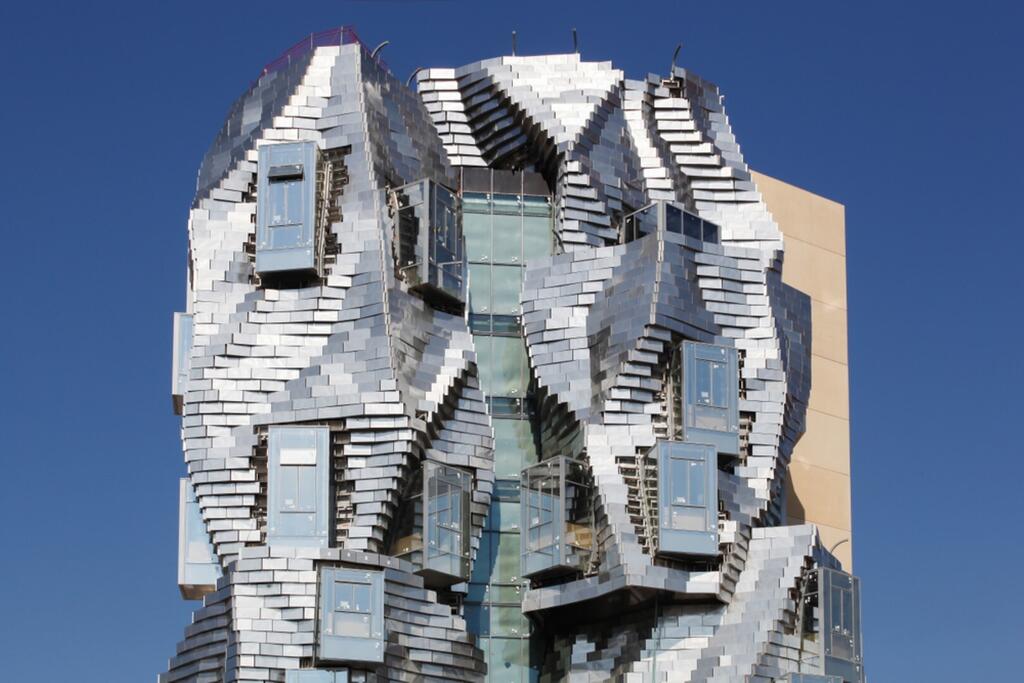

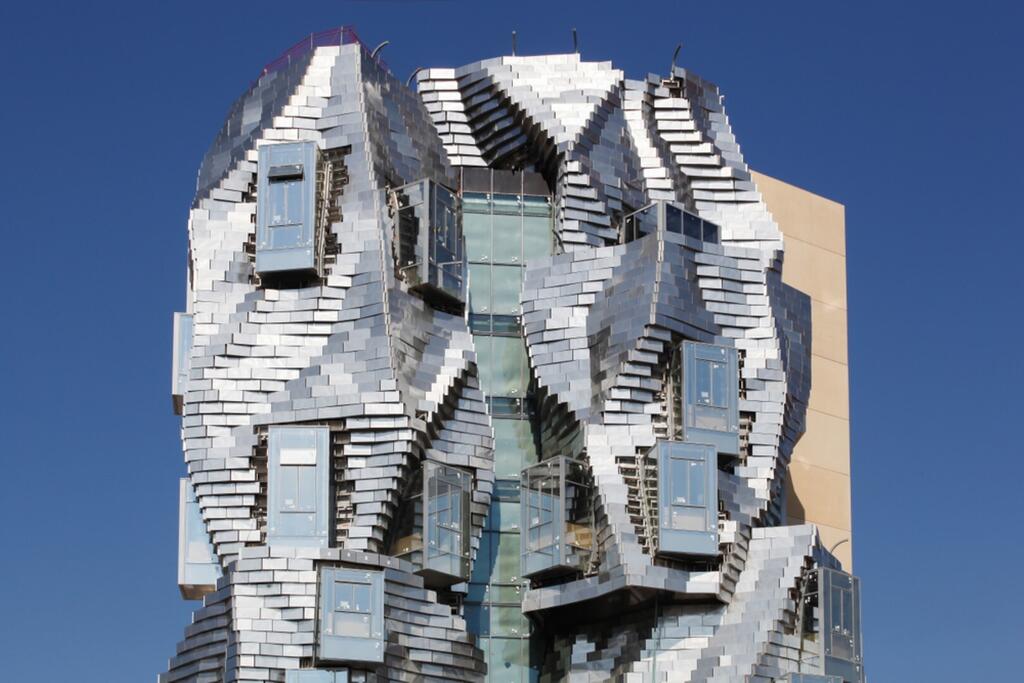

A new peak came in 1997 with the inauguration of the Guggenheim Bilbao. With its curving metallic facades, the building became a symbol of urban renewal and a defining example of how a single iconic structure can reshape a local economy, an influence later dubbed the “Bilbao effect.” Gehry set a precedent for cities around the world looking to attract attention through dazzling architecture. At times his buildings also drew criticism, including a project in Arles, in Provence, inaugurated about five years ago and covered with 11,000 gleaming aluminum panels that unsettled local residents.

6 View gallery

The Luma building in Arles, Provence, designed by Gehry, did not go over quietly

(Photo: ShutterStock)

The Walt Disney Concert Hall, completed in 2003, further cemented his standing. Other projects, including a Manhattan residential tower (2011) and the Pierre Boulez Saal in Berlin (2017), created in collaboration with conductor Daniel Barenboim, reflected his continuing search for creative freedom. In 2020, a controversial memorial to President Dwight Eisenhower opened in Washington, featuring a 24-meter-high metallic textile element, a nod to Gehry’s industrial aesthetic.

Until his final days, Gehry worked on high-profile projects, including a Louis Vuitton flagship store in Beverly Hills and a new concert center in Los Angeles. In a 2012 interview he said, “You go into architecture to make the world a better place. A better place to live and work. Not for ego.” He added, “Ego comes later. At first it’s pretty innocent.”