Over the past two years—and especially since the war with Iran began—Israelis have come to a renewed understanding of just how critical bomb shelters, fortified rooms (Mamad), communal shelters, and protective spaces are.

Once regarded as marginal, rarely used structures, they’ve suddenly become an inseparable part of daily life. Whereas during previous emergencies many people would only stay in a shelter for a few short minutes, recent days have seen countless civilians forced to remain in them for extended periods, even overnight.

11 View gallery

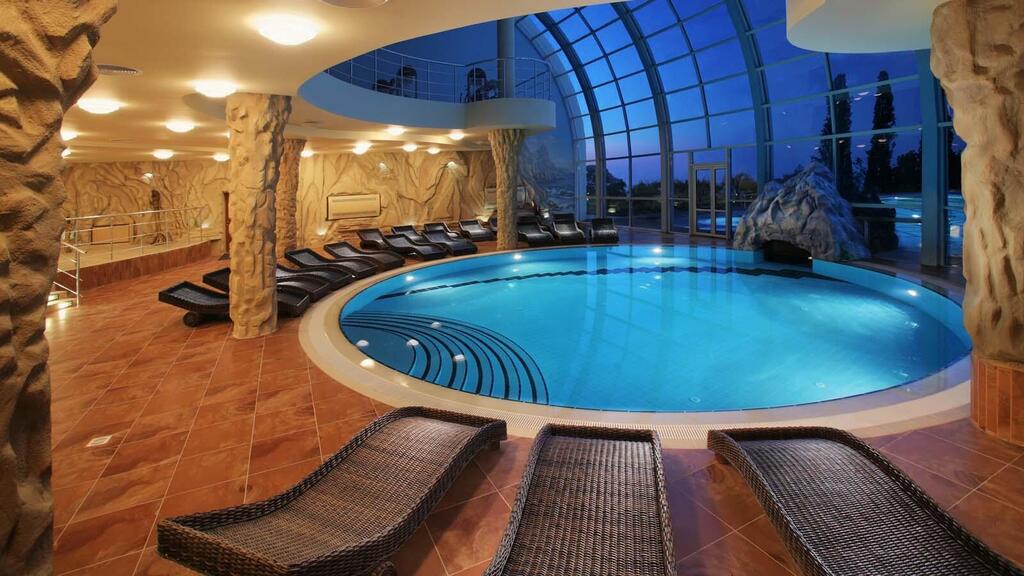

Descending to a luxury bomb shelter in West Virginia

(Photo: Andriy Blokhin/Shutterstock)

This reality has exposed the deteriorating condition of many shelters across the country. Numerous facilities are outdated, neglected, and used during peacetime as storage rooms—or worse, illegally converted into residential or business spaces.

Israel isn’t alone in its shelter infrastructure. Civilian bomb shelters—known internationally as shelters or fallout shelters—exist in many countries, particularly those with histories of war, ongoing security threats, or risks of natural disasters. Switzerland stands out as the only nation where, by law, every citizen must have access to a shelter. All new homes are required to include a private shelter or have access to a public one. As of the last decade, Switzerland had roughly 360,000 shelters—public and private—scattered throughout its mountains and cities, enough to house 100% of the population, complete with water, food, and ventilation systems for long-term stays.

Finland is another notable example: approximately 85% of its urban population is covered by shelter access, with around 50,000 shelters nationwide. The country employs advanced multi-purpose planning, with many spaces easily convertible into shelters in emergencies. Sweden boasts 65,000 public shelters, offering protection to roughly 70% of its population, and has ramped up civil defense infrastructure in response to Russian aggression. South Korea, under constant threat from the North, maintains about 17,000 shelters, many built into its subway system, and frequently tests its alert and guidance systems.

Japan—having suffered the atomic bombings of 1945—prioritizes natural disaster preparedness with shelters designed primarily for earthquakes and tsunamis, though recent discourse has emerged about the need for missile defense due to the threat from North Korea. In the U.S., most remaining shelters date back to the Cold War era. Many have since fallen into disrepair, though shelters still exist in government buildings, military facilities, and tornado-prone regions. A small subculture of survivalists has built modern fallout shelters in anticipation of apocalyptic scenarios.

In recent years, a radically different global approach has emerged: shelters are no longer conceived solely as emergency spaces. Many now serve dual purposes—functioning daily as swimming pools, basketball and squash courts, community libraries, hotels, or even cafés. When needed, they can swiftly convert back into life-saving havens. This fusion of everyday utility and emergency readiness raises important questions about Israel’s own approach. Can protected spaces be reimagined not only as temporary solutions but as thoughtfully designed, integrated parts of public life?

A leading example comes from Helsinki, Finland. Beneath the city lies one of the most impressive shelter facilities in the world: the Itäkeskus Swimming Hall. Carved deep into solid granite and opened in 1993, it houses four swimming pools, saunas, a gym, and a spa—serving hundreds of residents each day. In an emergency, it can be transformed within 72 hours into a sealed shelter capable of protecting hundreds of people. The natural rock provides thermal insulation, allowing for consistent temperatures year-round and significantly lowering energy and operating costs.

This facility reflects Finland’s broader civil defense strategy. With over 50,000 shelters capable of housing nearly the entire population, many are designed to support routine public use—housing gyms, water purification systems, even data centers. The underlying philosophy is clear: infrastructure should serve society today while remaining prepared for the worst.

The Itäkeskus center offers an inspiring vision—one where shelters are not grim bunkers but functional, aesthetic, and even inviting community hubs. It stands as a symbol of resilience: blending daily life, public investment, and civil protection into one harmonious space.

Luxury bunkers for the wealthy only

In recent decades, amid growing global uncertainty, a curious phenomenon has taken root: luxury survival bunkers. Aimed primarily at the global elite, these projects offer not only state-of-the-art protection during emergencies but also meticulously designed, high-comfort living environments.

11 View gallery

A bomb shelter that's also a country club in Finland

(Photo: City of Helsinki / Merja Huovinen)

One of the most striking examples is the Vivos xPoint project in South Dakota, developed on a former U.S. Army site used to store nuclear ammunition. It includes 575 reinforced concrete bunkers spread across more than 7,000 acres. Each bunker is intended for one family and starts at around $55,000—excluding renovations and customization, which can transform them into modern, luxurious living quarters. The company has even expanded its operations to Germany.

But Vivos’ vision goes beyond business. The goal is to create a fortified community for “chosen” individuals who can survive together through catastrophic events—nuclear war, climate disaster, pandemic, or global economic collapse.

11 View gallery

The entrance to a luxury, nightclub-style bunker in Beirut

(Photo: Bernard Khoury architects)

These bunkers emphasize not only safety but also lifestyle, with private libraries, advanced air filtration systems, entertainment consoles, smart kitchens, and sealed food and water supplies to last for years. Public criticism of such projects is widespread; many view them as status symbols for the ultra-privileged, enabling the few to escape global crises while the vast majority remain exposed and unprotected.

From Cold War relic to Airbnb

Ever spent your vacation inside an atomic shelter? If not, you might reconsider. In southern England, not far from the scenic Jurassic Coast—a UNESCO World Heritage Site—stands one of Europe’s most unusual vacation homes: a former underground military bunker, now repurposed as a luxury Airbnb rental.

Called The Transmitter Bunker, it was once a Royal Air Force radar station during World War II, protecting Britain from air raids. After decades of disuse, the structure was thoroughly renovated and now serves as a boutique lodging experience that draws history buffs, architecture enthusiasts, and curious travelers alike.

The transformation was led by the British architectural firm Corstorphine & Wright, who preserved the building’s historic integrity—retaining exposed concrete walls, low ceilings, visible wiring, and even a blast-shaped glass opening that brings in natural light and panoramic views. While the look remains authentic, it now includes modern amenities: a full kitchen, bathroom with shower, underfloor heating, smart TV, internet, and a wood-burning fireplace. The blend of industrial history with modern comfort creates a striking and memorable stay.

Shelters reborn in Chongqing

In Chongqing, a city in southwest China, dozens of air-raid shelters built during the Second Sino-Japanese War have been repurposed into cultural hotspots. Once grim, utilitarian spaces meant for emergency protection, many have been transformed by a government initiative into thriving venues—cafés, restaurants, art galleries, theaters, and bars.

A standout example is a bunker-turned-café in the heart of Chongqing. Retaining its raw, concrete aesthetic, it merges the shelter’s original structure with stylish, industrial design touches. Visitors sip lattes in vintage armchairs, surrounded by a backdrop of war-era architecture—and naturally, many snap photos for Instagram.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The project consciously balances preservation and modernization, improving ventilation, lighting, and accessibility while incorporating contemporary artworks. The result is a vibrant public space that bridges collective memory with the everyday lives of a younger, curious generation.

B018: Beirut's version of a German nightclub

In the Karantina district of Beirut—once an industrial zone devastated during Lebanon’s civil war—a bold vision rose from the rubble. Built in the late 1990s, B018 is a subterranean nightclub designed by Lebanese architect Bernard Khoury. Its bunker-like appearance and coffin-themed interiors reflect what Khoury calls “war architecture”: a confrontation with the past that also expresses resilience and rebirth.

11 View gallery

Air-raid shelter-a stone house in Jiulongpo District, Chongqing, China

(Photo: dyl0807, shutterstock)

By day, B018 looks like a sealed, forgotten shelter. But by night, a hydraulic metal roof opens to the sky, inviting hundreds of partygoers to a starlit underground rave. The venue quickly became a cultural landmark and a cornerstone of Lebanon’s electronic music scene.

Fusing industrial aesthetics with ritualistic space, B018 hosts up to 500 guests a night. Its design includes coffin-shaped furnishings, high-end sound systems, and unique climate infrastructure—all of which foster an immersive, cathartic experience. For many, music became a form of collective healing, a way to reclaim joy from the shadows of war.

In March 2024, the club temporarily shut down—not due to war, but because of a dispute between the Jabran family, who own the land, and the club’s operators. Its closure was felt as more than a pause in nightlife—it marked the silencing of a post-war heartbeat in the heart of Beirut.