Hong Kong’s skyline is known as one of the most striking symbols of urban density in the world. It is a landscape packed with concrete towers, glass walls and air conditioners, where nature seems to have no space at all. Yet a new photography series reveals another side of the city and shows that there is beauty even in its neglect.

Between rooftops, balconies and residential high-rises lies a living system of trees, birds and people who have made their way upward, alongside elements that are familiar to anyone who walks through an Israeli city: hanging and protruding air conditioners, exposed piping, cracks, patches of construction work, peeling plaster, soot, frayed electrical wires and weathered awnings.

Despite its reputation as a cold urban jungle, Hong Kong appears in these images as a place where nature quietly survives and even thrives. Vegetation climbs onto balconies, rooftops and window ledges. Perhaps from above, where the city can look almost inhuman, a new sense of harmony emerges. It raises the question of who adapts to whom: people to nature, or nature to people.

Anyone who has visited Hong Kong knows how extremely dense and vertical it is. The city grew upward because of limited space, a large population and high land prices. According to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, Hong Kong has more than 9,000 buildings that rise over 100 meters. This makes it one of the cities with the highest number of tall towers in the world. Between its high-rises and busy streets stretches a near-endless network of elevated walkways, highways and underground passages. The streets pulse almost every hour of the day, lights flash from every direction and the scenery is that of a lively metropolis. Perhaps too lively. There seems to be almost no corner free of human touch, planning or neglect.

Moments of pause within a dense city

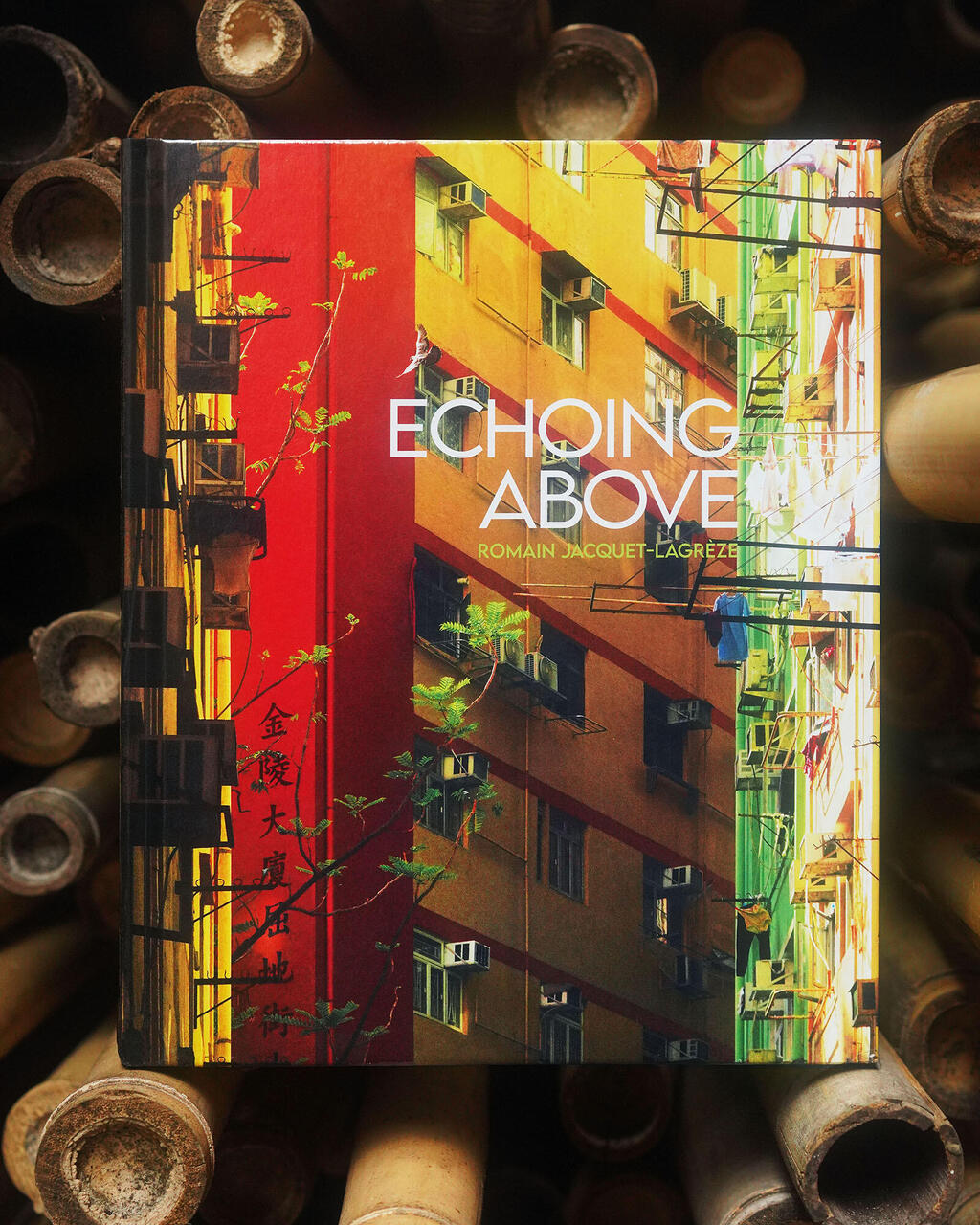

Within this unending urban fabric, sometimes reminiscent of large Israeli cities, French photographer Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze captures moments when the city seems to stop its fast pulse. In these brief pauses a quieter and more restrained side appears. In his new book, Echoing Above, published recently, Jacquet-Lagrèze documents what happens in Hong Kong’s skyward dimension. He photographs trees, birds and the facades of tall buildings that fill the city’s shifting heights. Through his lens he offers another perspective on the urban environment and highlights the ongoing dialogue between people, buildings and the nature woven between them.

“The unique density of Hong Kong has pushed the city to grow vertically,” Jacquet-Lagrèze said in an interview. “I was fascinated by how this density affects not only architecture but also the relationships between people and nature in this urban space.”

Bamboo scaffolding and a tree sprouting from a high gutter

Unlike cities in Israel and elsewhere, one of Hong Kong’s defining features, as shown in the book, is its traditional bamboo scaffolding. This centuries-old craft shaped the city’s urban character for generations. Hong Kong is one of the last major cities in the world where bamboo scaffolding is still used to construct and repair buildings. Built by skilled workers, the scaffolds are made of light, flexible bamboo poles grown in the region and bound into a system that is surprisingly strong and efficient. This traditional technique has been passed down through generations and supports everything from air conditioner repairs to cleaning or removing vegetation from building facades.

The scaffolding is attached directly to building exteriors, sometimes hanging at great heights with only a few anchoring points. Workers move across narrow planks and supports while gripping long bamboo poles with one hand. In recent years, however, safety regulations and concerns about flammability and material wear have reduced its use in public projects, gradually replacing bamboo with metal scaffolding. A significant chapter in the city’s architectural and cultural identity is slowly drawing to a close. The photographs capture different moments within the assembly process and reveal the material logic and simple beauty of these traditional construction techniques.

The book also highlights the remarkable resilience of the city’s trees. Some grow in seemingly impossible conditions, sprouting from thin cracks in gutters, walls and concrete facades. Between skyscrapers and within carefully planned human environments, these trees appear as persistent acts of nature that refuse to yield. Their roots coil around pipes, their trunks push between concrete blocks and their leaves spread across office windows. In Jacquet-Lagrèze’s images they become poetic symbols of life that insists on continuing, even in the densest places.

9 View gallery

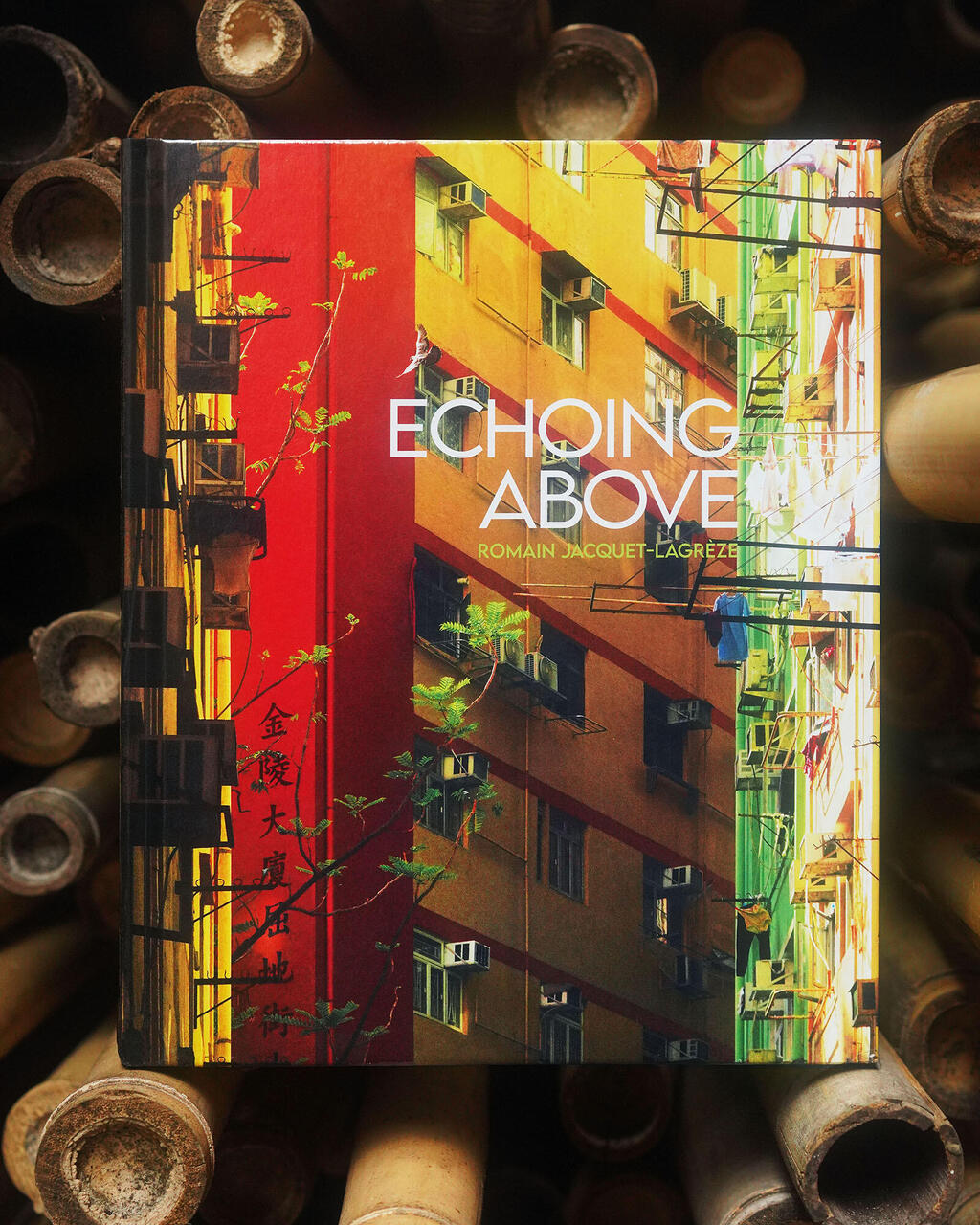

Finding beauty in decay. French photographer Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze

(Photo: Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze)

Nature woven into density and vertical construction

Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze, a French photographer who has lived in Hong Kong for 16 years, has closely followed the city’s transformations. He focuses on the relationship between people, architecture and the environment. His work documents the layers of urban space, from the street to the skyline, and examines how nature, density and vertical construction merge into Hong Kong’s unique texture. For him, photography is both a critical and aesthetic tool that makes it possible to understand a city through visual imagery rather than only through physical space.

9 View gallery

the book cover showcasing hong kong’s less polished sides

(Photo: Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze)

Perhaps, by looking at his work, we might learn to notice the unexpected beauty within Israeli cities as well.