When Isiah Thomas appeared Jan. 8 on the sports talk show “Run It Back,” he did not set out to revisit one of the longest and most personal rivalries in NBA history. But when the panel casually referred to the 1980s and 1990s as the league’s “golden generation,” Thomas bristled.

Sitting alongside host Michelle Beadle and former players Chandler Parsons and DeMarcus Cousins, the former Detroit Pistons star reacted sharply. Instead of celebrating the era in which he starred, Thomas turned his frustration toward how basketball history is framed — and toward Michael Jordan in particular.

“That’s what I don’t understand about your generation,” Thomas said. “You’re playing with what is probably the greatest basketball player ever, and you treat him like he’s nothing.”

Thomas argued that while Jordan is routinely labeled the greatest player of all time, LeBron James leads or ranks near the top in nearly every major statistical category. He pointed to Kevin Durant and Stephen Curry as further examples of modern greatness being overlooked.

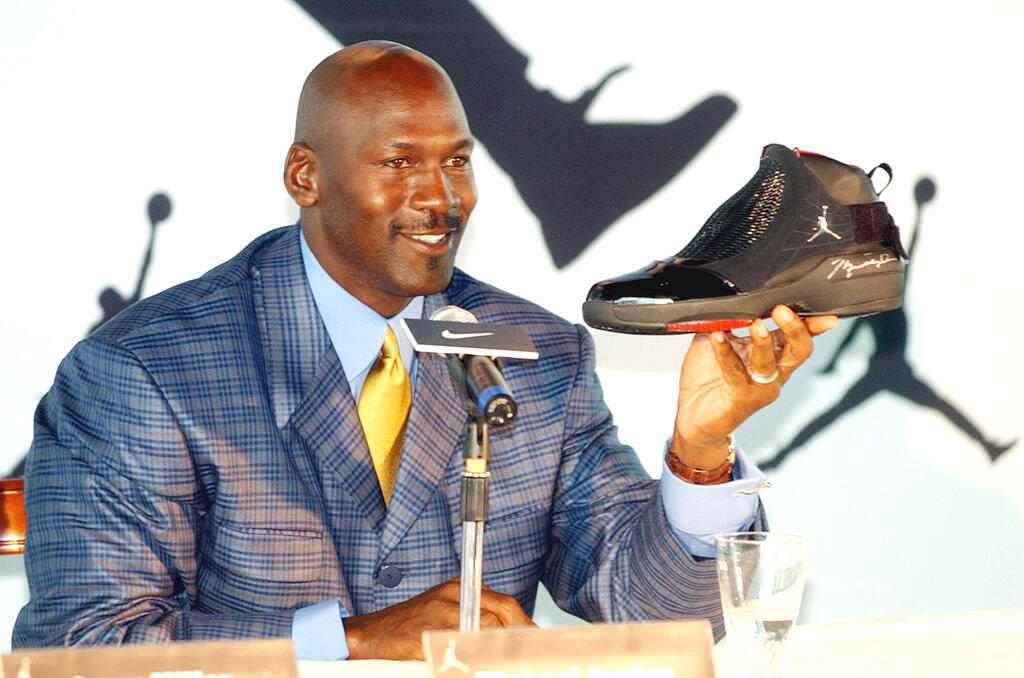

“And instead of uplifting your generation,” Thomas said, “you keep going back to our generation. You keep talking about the guy who brought you sneakers and tracksuits.”

The comment stunned the other panelists and quickly spread online. While debates over Jordan versus LeBron are common, Thomas’ framing — reducing Jordan’s impact to marketing — struck a nerve and reopened a feud that has defined both men’s legacies for nearly four decades.

Thomas’ resentment did not begin with television punditry. Its roots trace back to Chicago.

Born in 1961, Thomas grew up on the city’s West Side, the youngest of nine children. His father left early, and the neighborhood, shaped by white flight, poverty and crime, offered few safe paths. Basketball became his refuge. Thomas began playing at age 3 and emerged as one of the most gifted high school players the city had produced.

At his mother’s urging, he left Chicago to attend Indiana University, believing coach Bob Knight would provide structure and discipline. Thomas played two seasons, winning an NCAA championship in his second year. Knight famously bent his rigid coaching philosophy for Thomas, a rarity. In the 1981 NBA draft, Thomas was selected second overall by the Detroit Pistons, one pick after fellow West Side native Mark Aguirre.

Thomas transformed Detroit almost immediately. He became an All-Star as a rookie, dazzling crowds with his ball control, scoring ability and fearless competitiveness. Beyond the numbers, he embodied the Pistons’ identity.

Detroit built a team that rejected finesse in favor of confrontation. With Bill Laimbeer, Vinnie Johnson, Joe Dumars, Rick Mahorn and later Dennis Rodman, and under coach Chuck Daly, the Pistons became the “Bad Boys” — a team defined by suffocating defense and an “us against everyone” mentality. Thomas was the unquestioned leader, charismatic and ruthless, the engine of a group that thrived on hostility.

At the time, the NBA’s dominant narrative belonged to Magic Johnson and Larry Bird. Thomas wanted more than individual accolades. He wanted to take control of the league’s center stage.

That pursuit collided with Michael Jordan’s arrival.

Jordan entered the NBA in 1984, drafted by the Chicago Bulls. The symbolism was immediate and unavoidable. Jordan played his home games in the same city, and near the same neighborhoods, where Thomas had grown up.

But the rivalry went deeper than geography. Jordan arrived with unprecedented hype, becoming a global sports, cultural and fashion phenomenon almost instantly. Before he had won anything, he was already anointed as the league’s future. Thomas, steeped in old-school ideas of earning respect on the court, bristled at the attention.

According to NBA lore, tensions surfaced early. At the 1985 All-Star Game in Indianapolis, players led by Thomas allegedly froze Jordan out of the offense. Thomas has always denied orchestrating such a move. Years later, Jordan thanked Thomas during his Hall of Fame induction, saying the experience fueled his motivation.

The first game after that All-Star break came in Chicago. Jordan scored 49 points, with 15 rebounds, five assists and four steals. Legend or not, the rivalry was sealed.

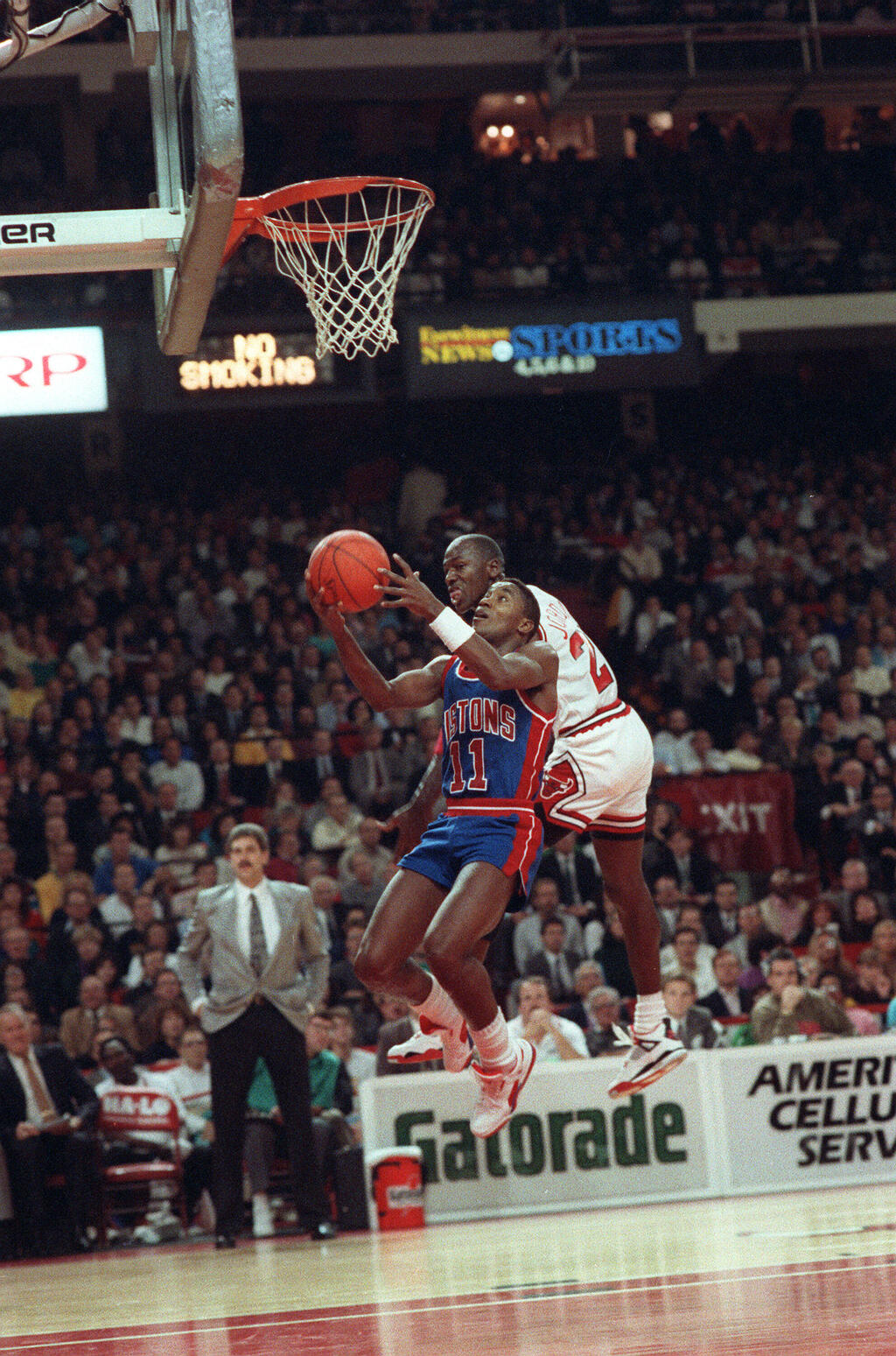

Detroit’s response was calculated and physical. The Pistons developed the “Jordan Rules,” a defensive scheme designed to force the ball out of Jordan’s hands and punish him whenever he attacked the basket. The playoff battles that followed were brutal, filled with hard fouls, bruises and lingering animosity.

Detroit eliminated Chicago from the playoffs three straight years before breaking through to win back-to-back championships in 1989 and 1990. Thomas had reached the pinnacle of the sport. By any measure, he belonged among the game’s greats.

The bitterness, however, never dissipated.

In 1991, when the Bulls swept Detroit in the Eastern Conference finals on their way to Jordan’s first title, Thomas led the Pistons off the court with seconds remaining, refusing to shake hands. It was a violation of an unwritten NBA code. The moment was replayed endlessly decades later in ESPN’s “The Last Dance,” released during the COVID-19 pandemic. Watching the footage, Jordan called Thomas an “idiot” and an “asshole.”

Later that year, Thomas drew further condemnation when he suggested that Magic Johnson’s HIV diagnosis was linked to Johnson’s lifestyle — a remark widely viewed as insensitive and cruel, especially given their prior friendship.

When USA Basketball assembled the Dream Team for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, Thomas’ fate was sealed. Jordan made clear he would not participate if Thomas were included. Other stars — including Scottie Pippen, Charles Barkley, Karl Malone, Bird and Johnson — reportedly shared that position. Thomas, still among the best point guards in the world, was left off the roster. The final sting came from the fact that the team was coached by Chuck Daly, his longtime Pistons mentor.

After injuries ended his playing career, Thomas’ post-NBA path proved turbulent. He clashed with ownership in Toronto, was fired in Indiana and worked as a television analyst for NBC. He bought the Continental Basketball Association in 1999 and watched it collapse within two years. His tenure as president of basketball operations for the New York Knicks produced some of the franchise’s worst seasons despite massive payrolls. In 2007, the Knicks paid $11.5 million to settle a sexual harassment lawsuit brought by a senior executive.

Thomas later failed as a college coach, returned to broadcasting and, in 2015, was controversially appointed president of the WNBA’s New York Liberty.

Despite the setbacks, Thomas insists his criticism of Jordan is not rooted in jealousy.

“I’m not a hater,” he said during the recent broadcast. “I’m a historian of the game. I’m talking facts. In every sport, the greatest player usually holds the records. Kareem does. LeBron does. Jordan doesn’t.”

The claim remains contested. Jordan still holds the highest career scoring average in NBA history, in both the regular season and the playoffs, and won a record six NBA Finals MVP awards.

Decades after their final game against each other, the rivalry between Thomas and Jordan shows no sign of fading — not because of championships or statistics, but because for Thomas, Jordan represents the moment when history chose someone else.