In honor of the great Exodus from Egypt, this Passover we’re setting out to track down traces of ancient Egypt: Where can you find a locally made pyramid? What exactly is Pharaoh Ramesses III wearing in the statue sculpted in his image? Which Israeli site has revealed remnants of an Egyptian palace, scarabs bearing the names of pharaohs, and even a “letter” documenting a major wheat deal? And in which city did they build a triumphal arch to console Pharaoh after a tough battle? Fill up your water bottles and let’s go.

Tel Afek: Pharaoh near Rosh HaAyin

Tel Afek, also known as Antipatris or Tel Rosh HaAyin, is located at the source of the Yarkon River, just about 3 km east of Petah Tikva. This was once the site of ancient Afek, a city mentioned in archaeological records as far back as the second millennium BCE. Over the centuries, Afek and its surroundings played host to a parade of regional superpowers. Egyptians, Philistines, Canaanites, Hittites, Hellenists, Romans, Ottomans, and even the British—each left their mark here in the form of inscriptions, artefacts, and ruins.

Tel Afek also appears in a series of ancient Egyptian sources—papyrus scrolls, inscriptions and magical texts written on pottery shards and figurines. These so-called “execration texts” were used to cast curses on the names they listed. In the Bible, however, the site is mentioned only from a later period, as a Philistine city: “Now the Philistines gathered all their armies to Aphek” (I Samuel 29:1).

Excavations at the site have uncovered a treasure trove of Egyptian relics, including the remains of a governor’s palace believed to have been built during the reign of Ramesses II—whom some identify as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Other finds include a scarab bearing his name, a small hieroglyphic tablet, and an Egyptian seal ring inscribed with a blessing to the god Amun.

One of the site’s most remarkable finds is a complete 41-line letter written in Akkadian, describing a major wheat sale—on the scale of a full cargo ship. The letter was sent by a governor of a city in northern Syria to a senior Egyptian official, and the writer notes that he included a gift for the official: valuable dyed wool. Both the sender and the recipient are known from other sources as active figures during the reign of Ramesses II in the 13th century BCE.

The Egyptian governor’s palace is not the large fortress that towers above the tel. That current fortress was built during the Ottoman period, in the 16th century CE, atop the ruins of much older structures. Many mistakenly call it “Antipatris Fortress,” after the city King Herod built here and named in honor of his father—but its actual name is Binar Bashi, which means “Rosh HaAyin” in Turkish. Remains of the earlier buildings were uncovered beneath it in archaeological excavations, and reconstructions of them can be seen at the site.

For more information and visitor guidelines for Tel Afek, visit the Israel Nature and Parks Authority website.

Horvat Midras: A pyramid, Israeli style

Who says you need to travel to Giza to see a pyramid? All it takes is a drive to the Adullam region. In Adullam Park, just south of the community of Tzafririm, lie the remains of an ancient settlement known as Horvat Midras. Thought to have been founded during the Persian period (around 500 BCE), the site reached its peak as a Jewish village between the 1st century BCE and the 2nd century CE.

6 View gallery

remains of an ancientRemains of the ancient settlement of Horvat Midras

(Photo: Dr. Yaron Zafern)

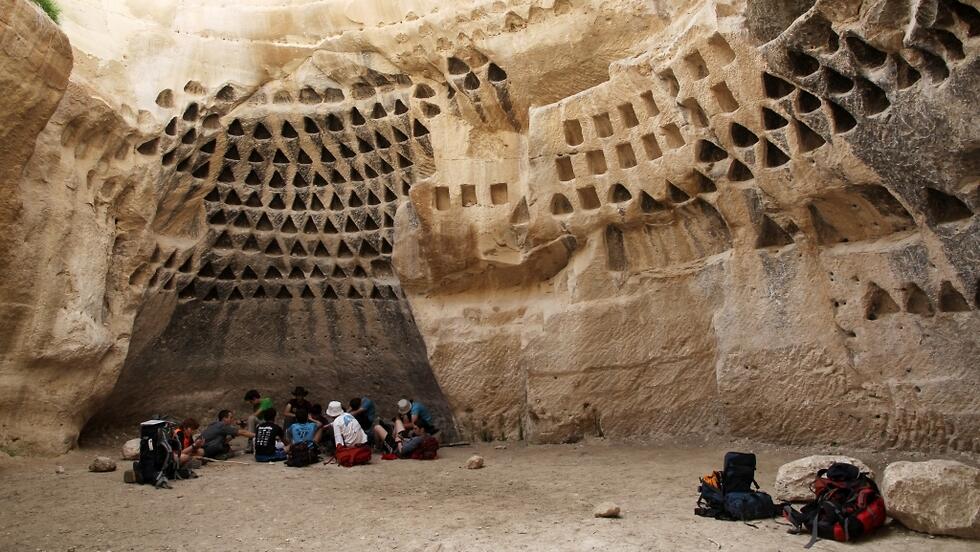

Spanning roughly 250 dunams, the site includes an impressive 56 underground caves and cisterns, as well as ritual baths, columbarium installations, burial complexes, agricultural facilities—and a network of hidden tunnels likely used by Jewish fighters in their revolt against the Romans. Today, visitors can crawl through these very tunnels by flashlight (safety measures required, of course) and get a real feel for the past beneath their feet.

The site also features a striking burial monument in the shape of a pyramid, likely inspired by the iconic structures of ancient Egypt. Researchers believe it was built for a Jewish family, and there may be a burial chamber hidden beneath it.

Constructed from massive, precisely cut stones quarried from the surrounding rock, the pyramid once stood taller—three upper levels are now missing. Even so, it was once tall enough to serve as a lookout point. Today, it reaches a height of about 3.5 meters, with each side measuring roughly 10 meters in length, earning it the Arabic name El Montar—“The Lookout.”

The Jewish settlement at the site was destroyed during the Bar Kokhba revolt. Centuries later, a church with elaborate, colorful mosaics was built atop the ruins—but it too was lost, brought down by an earthquake in 749 CE. The church was uncovered in excavations in 2011.

For more information and hiking tips for Horvat Midras, visit the Israel Nature and Parks Authority website.

Jaffa: Triumphal arch as a consolation prize

That same Pharaoh whose traces were found at Tel Afek—Ramesses II—visited Jaffa more than once, back when it was under Egyptian control, just like many other Canaanite cities at the time. But one visit stood out above the rest: it came after the bloody Battle of Kadesh, fought around 1274 BCE in what is now western Syria. In that legendary clash, the Egyptian and Hittite empires—two giants of the ancient world—went head-to-head.

The battle ended without a clear victor, but Ramesses II, who barely escaped with his life, emerged battered and bruised. On his way south back to Egypt, he passed through Jaffa—where locals, eager to lift the spirits of the humbled Pharaoh, had built him a grand triumphal arch in his honor.

The arch was built from kurkar, the coastal sandstone typical of the region, and was originally painted in vivid colors. Hieroglyphic inscriptions carved into the stone listed the names and titles of Ramesses II. Near the reconstructed pillars, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a pharaonic fortress that was destroyed in a great fire—today, only one large wall survives. The original pillars of the arch are now on display at the Old Jaffa Museum, just a short walk south on Jaffa Port Street.

In Ramesses’s time, the arch stood proudly at the city’s entrance. Today, it finds itself right in the heart of the city, within Gan HaPisga—literally, “Summit Garden”—a high vantage point with sweeping views of the coastline. The garden is also home to cannons from Napoleon’s time, and the sculpture The Gate of Faith by artist Daniel Kafri, which was inspired by the ancient Egyptian arch. The artwork depicts the promise of the land to the three Patriarchs, represented through three pivotal moments: the Binding of Isaac, Jacob’s dream, and the conquest of Jericho.

The period of Egyptian rule in Jaffa is also recounted in the Harris 500 Papyrus, which tells of the city’s clever conquest by the army of Pharaoh Thutmose III. According to the story, Egypt had laid siege to Jaffa but failed to breach its defenses—so the Egyptian general resorted to trickery. He invited the city’s governor to a feast outside the walls, claiming he wished to defect with his family. Once the unsuspecting governor arrived, the general struck him down and bound him. Then, 200 large baskets were sent into the city, supposedly as a grand gift—but hidden inside were Egyptian soldiers. Once inside the gates, they leapt out and took the city from within.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The tale echoes the legend of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves from One Thousand and One Nights, and the Greek myth of the Trojan Horse. Whether it actually happened that way is up for debate—but one thing’s certain: Pharaoh was eager to boast of Jaffa’s capture, even if it took a little creative storytelling to seal the glory.

Beit She’an: Ruler of the Empire in sandals

Ancient Beit She’an, one of the most impressive archaeological sites in Israel, is best known for its grand Roman-era remains—bathhouses, temples, a colonnaded theatre, and sophisticated water systems that have stood the test of time. The city also appears several times in the Bible, including in the story of the Israelites entering the land, where it is listed as part of the territory of the tribe of Manasseh (Joshua 17:11). But the history of Beit She’an goes back much further—at least to the prehistoric era. Among the many layers uncovered at the site are remains from the time when the city was under Egyptian rule.

The city was conquered by the Egyptians in the 15th century BCE, and they turned it into a regional center of their rule. Archaeologists uncovered the remains of a large structure whose high-quality construction and finds suggest it served as the residence of the Egyptian governor—likely housing a succession of officials over time. Among the rare treasures from the Egyptian period discovered at the site are a statue of Ramesses III and two stelae from the reign of King Seti I.

6 View gallery

Antiquities at Tel Beit She’an

(Photo: German-Israeli Tell Izṭabba ̣Excavation Project)

The statue portrays Ramesses III life-sized, seated on a throne, wearing a short kilt and a wig adorned with the royal cobra. Around his neck is a beaded necklace, sandals on his feet, and several of his royal names carved into his shoulders. The statue is made from local basalt, and researchers believe it was created in Canaan by Egyptian sculptors. Though badly damaged—both by the destruction of the temple in which it once stood and by deliberate defacement—it still radiates unmistakable royal grandeur.

The two victory stelae recount the triumphs of Seti I—father of Ramesses II—over his Canaanite enemies in the Beit She’an region. One of the inscriptions describes the king’s foes as those “who do not recognize the ruler, strong as a falcon, like a mighty bull, wide of stride, sharp-horned, wings outstretched, his limbs as firm as bronze, with the power to destroy all of Canaan.”

These remnants from the Egyptian period were uncovered at Tel Beit She’an, located within the national park. For directions and more information about Beit She’an National Park, visit the Israel Nature and Parks Authority website.

Ancient Shiloh: Site of the Tabernacle after the Exodus

After the Israelites entered the Promised Land following the Exodus from Egypt, their spiritual and religious center was at ancient Shiloh. Perched on a gentle hill, this was the site of the Tabernacle and the Ark of the Covenant for 369 years, according to Jewish tradition—spanning the eras of Joshua and the Judges. Here, Joshua divided the land among the tribes of Israel. Here, Hannah, barren and brokenhearted, prayed for a child. And here, young Samuel grew up and rose to become a leader of the nation.

Over the years, numerous archaeological excavations have been carried out at ancient Shiloh. Among the discoveries was a figurine bearing an Egyptian inscription from the Iron Age—evidence of ties with the Egyptian kingdom—and a 3,000-year-old scarab, a type of Egyptian seal, that resonates with the biblical account of the Israelites' arrival in Canaan after the Exodus.

Today, the site is a well-maintained archaeological park, complete with an observation tower and a museum showcasing artifacts that reflect continuous settlement from the Bronze Age through the early Arab period (7th century CE). Visitors can explore intricate mosaics, the remains of two churches—one of them among the earliest ever discovered in Israel—as well as a mosque and a synagogue. The site also has family-friendly activities during Passover.

So what are you waiting for? Pack your bags and hit the road!

This article is courtesy of Mashav Channel – What's Jewish in Israel. Click here for a survey about Jewish content in Israel