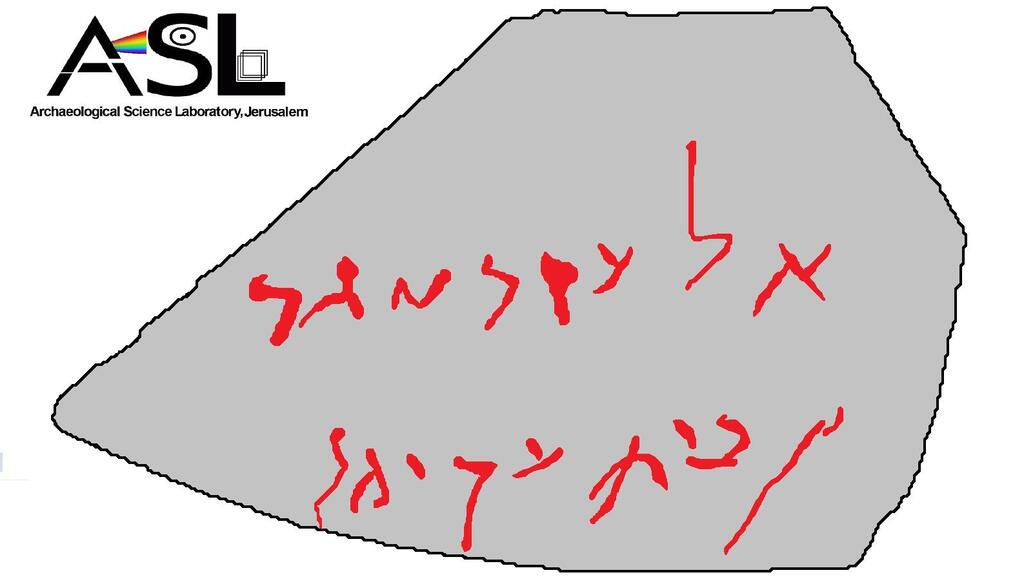

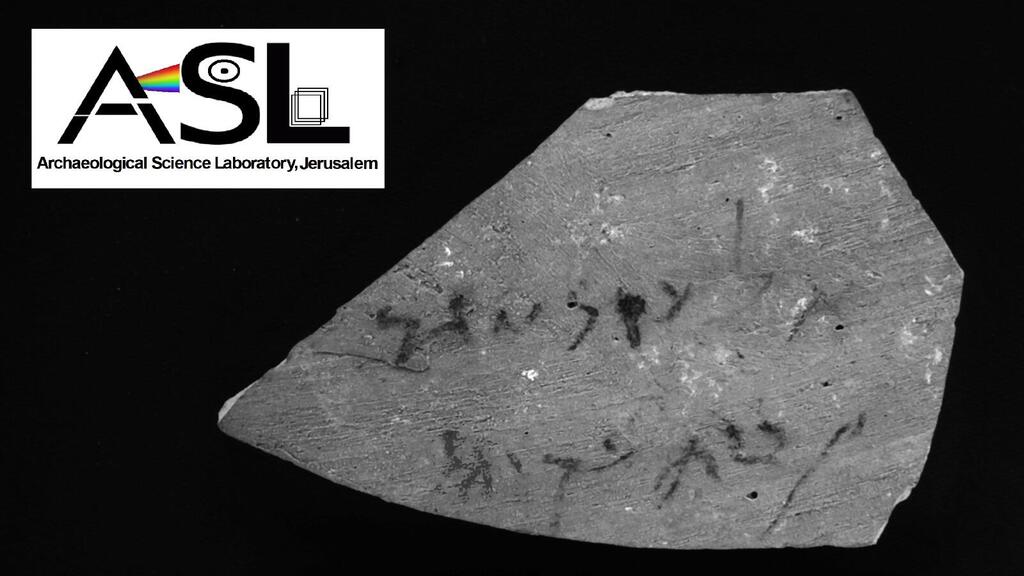

Researchers have deciphered a 2,000-year-old Aramaic inscription on a pottery shard discovered at the Alexandrium Fortress (Sartaba) in the Jordan Valley. The text reads: “Eleazar bar Ger… from Beit Akiman.” Bar-Ilan University scholars analyzed and deciphered the inscription using advanced imaging technology developed by Jerusalem’s Azrieli College of Engineering.

The shard, excavated in the 1980s by the late Hebrew University archaeologists Prof. Yoram Tsafrir and Yitzhak Magen but never fully published, is among 12 ostraca (inscribed pottery fragments) found at the site. These include texts in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek, now under study by Prof. Esther Eshel from Bar-Ilan University and Prof. Haggai Misgav from the Hebrew University.

5 View gallery

The ostrocon found in the Alexandrium Fortress

(Photo: Archeological Labratory Jerusalem)

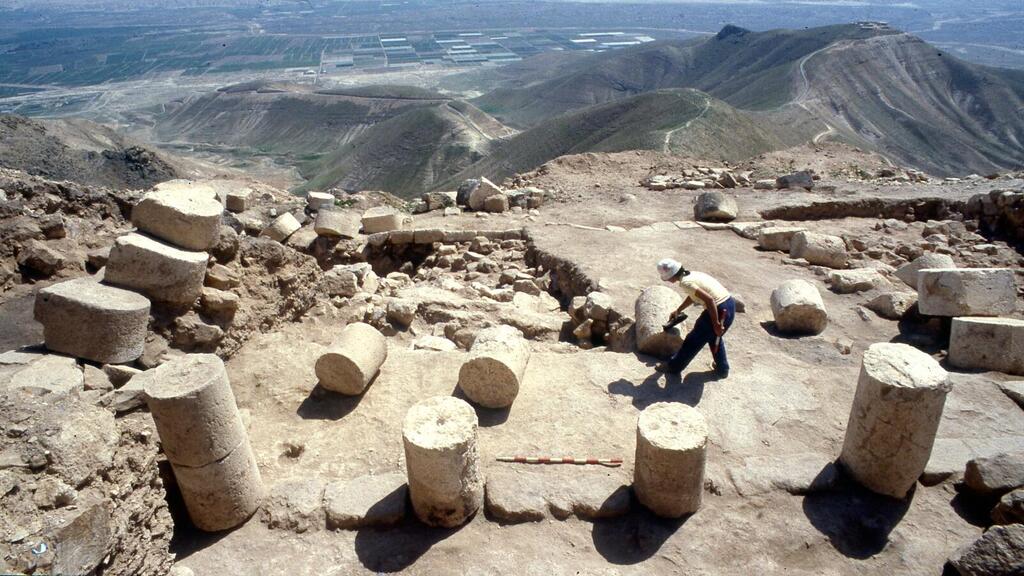

The Alexandrium Fortress, perched like an eagle’s nest atop Mount Sartaba overlooking the Jordan Valley, derives its name from the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus. A key Judean stronghold during the Second Temple period, it flourished in the first century BCE as a fortified palace for Hasmonean rulers and Herod the Great.

The site is noted as the burial place of the last Hasmonean royals, where Herod imprisoned the Hasmonean princess Mariamne and her mother Alexandra and as one of three fortresses where Herod hosted Marcus Agrippa (son-in-law of Roman Emperor Augustus) during his visit to Judea.

A limited Hebrew University excavation 40 years ago revealed remnants of a grand columned structure from the Hasmonean and Herodian periods, overlooking the Jordan Valley. Surveys also documented an advanced water supply system and Roman siege works.

Recent excavations revealed a rare Tiberius-era coin (circa 19–20 CE), likely minted in Syria, suggesting Roman activity during the First Jewish Revolt (66–73 CE). Ostraca bearing Jewish names, similar to those linked to rebels at Masada and Herodium, hint at possible insurgent use of the site.

A new imaging method — combining hyperspectral photography, artificial intelligence and image fusion — enabled researchers to recover faded texts invisible to the naked eye.

Prof. Eshel and Prof. Misgav noted that the name “Eleazar” — like other Hasmonean dynastic names (Judah, Jonathan, Simon, John) — was common among Jews in the late Second Temple-era Judea.

The term “bar Ger” (son of Ger) may indicate that Eleazar’s father was a convert (ger), akin to the name “bar Gira” found on a Jerusalem-area burial ossuary. Alternatively, it could be the beginning of a surname like “Geryon.”

The Talmud references a figure named “Judah ben Gerim” (Judah son of converts), who allegedly informed Romans about Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. Some scholars suggest his name might have been “ben Geris,” similar to “Hillel ben Geris” mentioned in Bar Kokhba Revolt-era documents from the Judean Desert.

Dr. Doron Sar-Avi of Herzog Academic College, a co-researcher on the inscriptions, noted: “‘Beit Akiman,’ cited as Eleazar’s origin, was previously unknown. It may correspond to sites near Wadi Khamuniyya, west of Sartaba, where Second Temple-era villages were documented.”

Dr. Dvir Raviv, leading renewed excavations at Sartaba, added, “These 2,000-year-old inscriptions shed light on the site’s history as a royal fortress for the Hasmoneans and Herod. Ostraca with Jewish names and parallels to rebel-linked texts at Masada support the possibility of insurgent activity here during the Great Jewish Revolt.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

Benny Har-Even, head of the Archaeology Staff Officer Corps, said, “Resuming work at Sartaba-Alexandrium after 40 years is a historic moment. This inscription’s decipherment highlights the site’s immense potential. We anticipate further discoveries illuminating the Hasmonean-Herodian fortress and ancient Jewish settlement in the region.”

“This finding reaffirms the Jewish people’s unbroken bond with Israel,” Heritage Ministry Director-General Itay Granek added. “Eleazar’s name, etched on a shard at a key Hasmonean site, joins a chain of evidence attesting to continuous Jewish presence across the land—from the Jordan Valley to Jerusalem.”