In Bhutan, a tiny, magical Buddhist kingdom tucked between Tibet and India, spirituality isn't a relic of the past—it is the nation's beating heart. Tradition is woven into everyday life across the country, which was isolated from the rest of the world until just a few decades ago. Colorful prayer flags flutter in the wind, daily rituals unfold in every corner, monks in orange robes walk the streets, every home includes a shrine room, and the scent of purifying incense rises each morning from village houses.

Thanks to its deep Buddhist roots, Bhutan is the only country in the world whose constitution prioritizes GNH—Gross National Happiness—over GDP. This guiding principle was introduced in the 1970s by the fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, who famously declared, “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross Domestic Product.” Since then, Bhutan has committed to an approach where economic growth serves as a means to a wiser, better life for individuals, communities, nature, and cultural heritage.

Bhutan’s constitution, drafted about 20 years ago when the king initiated a transition to democracy as a balance to the inherited monarchy, reflects this philosophy. Inspired by a wide review of global constitutions, it includes a clause requiring public servants—including the prime minister and the king—to retire by age 65. The former king himself voluntarily stepped down at 51, handing the crown to his son, the current monarch.

The philosophy of GNH is rooted in balance—honoring the past while cautiously shaping the future. Modernity exists in Bhutan, but it arrives slowly, by choice. There isn’t a single traffic light in the country. Television and the internet were introduced only in 2000. High-rise buildings are prohibited, and the national highway speed limit is 60 km/h. Tourism follows a “low volume, high value” model, with a $100 daily tourist fee designed to improve services while preventing overcrowding in a country of just 700,000 people.

At the heart of Bhutan’s spiritual tradition stands Guru Rinpoche, also known as Padmasambhava or the “Second Buddha.” A revered 8th-century teacher, he brought Vajrayana Buddhism to Bhutan and Tibet after being summoned by a local ruler seeking healing. More than a historical figure, Guru Rinpoche is celebrated in Bhutanese mythology as a spiritual master, mystical healer, dance creator, and sacred treasure revealer. His serene face, thin mustache, and piercing eyes appear in nearly every temple and monastery, surrounded by silk scarves, incense smoke, and flickering butter lamps.

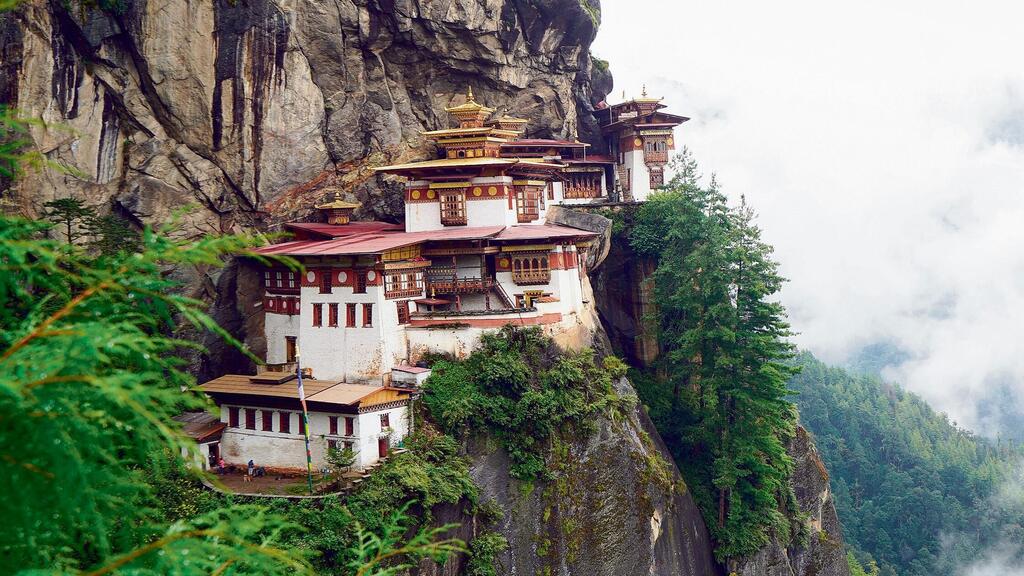

The most iconic site associated with him is Paro Taktsang—Tiger’s Nest Monastery—perched dramatically on a cliff 900 meters above the Paro Valley. Built in the 17th century around the cave where Guru Rinpoche meditated, the monastery defies gravity and logic. According to local lore, he arrived here on the back of a flying tigress to subdue a malevolent spirit.

Guru Rinpoche brought to Bhutan a distinct way of life that still resonates today. Core values of Vajrayana Buddhism—generosity, compassion, and the alleviation of suffering—are deeply felt in every journey through the country. Encounters with hotel servers, market vendors, fortress guards, temple monks, and senior officials are often marked by uncommon warmth and kindness.

His legacy is especially alive during Bhutan’s spiritual festivals, held year-round across the kingdom. Each festival—usually lasting three days—features dazzling performances in elaborate costumes and ancient masks, hypnotic dances, cymbal crashes and booming drums, folk troupes, sacred clowns, and crowds in festive attire. Festivals always fall on the 10th of the Bhutanese lunar month—a date believed to mark Guru Rinpoche’s significant appearances as he fought dark forces and spread Buddhism.

These festivals, known as “Tsechus” (literally “Tenth Day”), began in the 17th century under Bhutan’s unifier, Zhabdrung, and are still celebrated in much the same way today, sometimes simultaneously in different regions. The most popular Tsechus—drawing large audiences—are held in Thimphu (September/October), Punakha (February/March), and Paro (April). Smaller festivals, however, offer more intimate experiences: meeting masked dancers, chatting with musicians, and joining locals for picnic-style lunches.

Bhutanese families often travel long distances on foot to attend, arriving in their most elegant traditional attire—men in ghos and women in kiras. Elderly women wear heirloom gemstones and silver jewelry, while children run about, friends reunite, young women pose for photos, and cheerful volunteers in orange tunics help keep order.

At the center of every festival are the sacred mask dances, or “Cham,” performed by monks or trained locals in vibrant robes and dramatic masks. Each dance follows a precise choreography passed down orally for generations, originating from spiritual masters centuries ago. For Bhutanese, Cham is not just a performance—it’s a spiritual practice, cultural preservation, and communal bonding. Every mask, garment, and movement carries layered meaning, and watching the dances is believed to be both cleansing and liberating for performers and viewers alike.

Dozens of dances dramatize Buddhist myths, with names like “Dance of the Heroes,” “Dance of the Stags,” “Drum Dance,” “Black Hat Dance,” “Dance of the Wrathful Deities,” “Dance of Judgment Day,” and “Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche.” Each one conveys Buddhist messages about the impermanence of life, protective forces, the power of compassion, the need to prepare for death, and the triumph of good over evil.

Among the most striking is the Black Hat Dance, performed by monks wearing tall black hats adorned with mystical symbols. This dance symbolizes the protection of Buddhism and the subjugation of evil. According to tradition, Guru Rinpoche himself danced it when consecrating Himalayan temples, using precise movements to purify the ground and sanctify the site.

One of the most elaborate performances is the “Eight Manifestations of Guru Rinpoche,” portraying the master’s eight different incarnations as he taught the Dharma. Each is represented by a unique masked dancer, illustrating the Buddhist belief that spiritual teachers adapt to their audience’s needs.

Amid all the solemnity, Bhutanese clowns—called “Atsaras”—frequently burst onto the scene. Wearing comical outfits, red wooden masks, and carrying wooden phalluses, they parody the dancers, perform skits, collect donations, and remind spectators that humor also has a place on the path to enlightenment. Despite their silliness, the Atsaras play a vital traditional role: blending entertainment with teaching and using laughter to make complex Buddhist ideas more accessible. Their presence offers joyful pauses in the ceremonial atmosphere and strengthens the community’s bond with its heritage.

Visiting Bhutan feels like stepping into a legend. It’s a journey through living history, full of smiling Bhutanese people who radiate warmth and calm. It's also an invitation to slow down—to adopt a mindset of reverence and attentiveness, in a place where not only time moves differently, but so does the heart.

In an era of global acceleration toward modernity, competition, and consumerism, Bhutan stands out as a place where slowness is a treasured asset. Whether you're attending a Tsechu festival, spinning massive prayer wheels, or hiking along a quiet mountain path, the feeling is not just of observing a landscape, but of entering a way of life.

The local guides, required for every visitor (see details below), serve not only as narrators but as living bridges to a different worldview, offering not just facts but the beliefs and emotions that shape Bhutanese life. As one smiling Bhutanese guide put it: “As a tourist, you don’t just pass through Bhutan. You let Bhutan pass through you.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

How to visit: Bhutan can be visited on a group tour or as an independent traveler. In both cases, travelers must book through a licensed local tour operator and be accompanied by a local guide and driver, with an itinerary set in advance.

Visa: A visa is required and must be arranged in advance, along with a $40 fee and a $100 per-person, per-day sustainable tourism fee.

Getting there: Flights to Bhutan are offered by the national airline, Druk Air, and the private Bhutan Airlines. Departures are available from Delhi, Bangkok, Kathmandu, Dubai, and more (each plane holds around 120 passengers). With prior coordination, overland entry is possible via border crossings from northern India.

When to go: The best times to visit are in the fall (September–November) and spring (March–June). Winter (December–February) is cold and dry, and also a possible travel window. The monsoon months of July and August are less recommended.

Dr. Nimrod Sheinman is a pioneer of mind-body medicine in Israel and a mindfulness-in-education expert. Over the past decade, he has developed a deep connection to the people, sites, and traditions of Bhutan