In the remote reaches of northeastern Mongolia—far from the grand courts and bustling cities of medieval East Asia—archaeological discoveries buried beneath the earth are shedding light on a hidden chapter of empire: a story of survival, adaptation and daily life on the margins.

A new study led by doctoral candidate Tikvah Steiner from the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, under the supervision of Prof. Gideon Shelach Lavi and Prof. Rivka Rabinovich, has unearthed a remarkably rich zooarchaeological assemblage at “Site 23.”

5 View gallery

Some of the findings in the expedition in Mongolia

(Photo: Tal Rogovsky, Hebrew University)

The site, a guard post along a 4,000-kilometer (2,485-mile) wall system marking the boundaries of the Liao Empire (916–1125 CE), offers a rare glimpse into the lives of those who defended the empire’s edges.

Published in Archaeological Research in Asia, the findings come from a broader ERC-funded project titled " The Wall: People and Ecology in Medieval Mongolia and China ", directed by Prof. Shelach Lavi of the Hebrew University’s Department of Asian Studies.

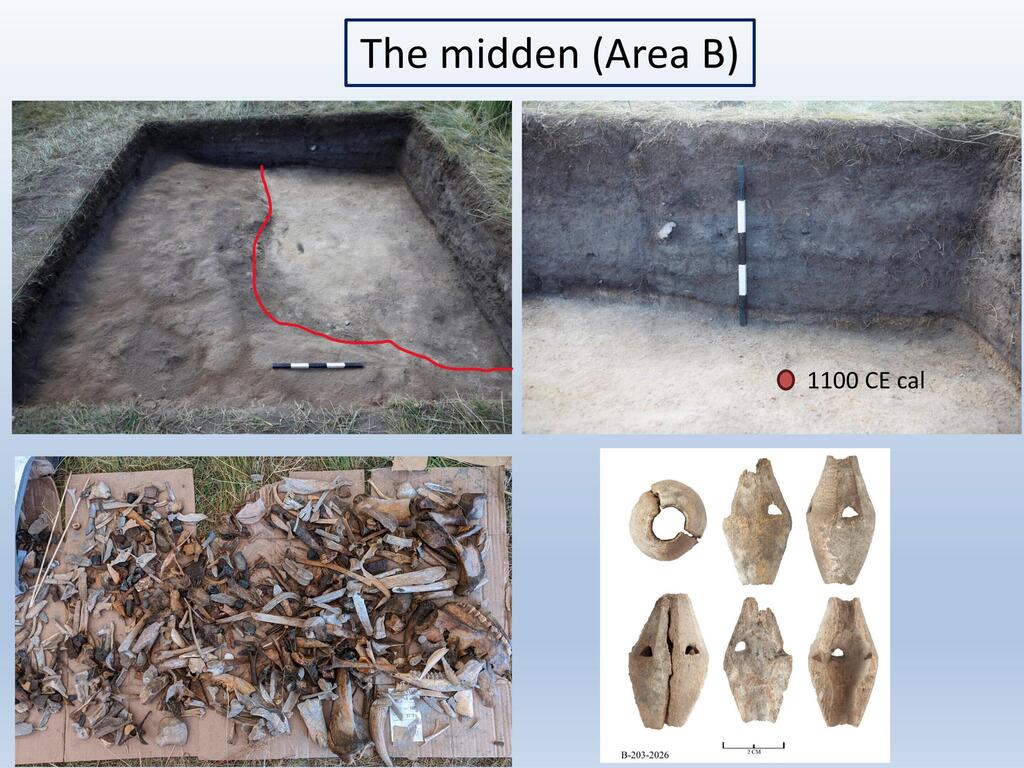

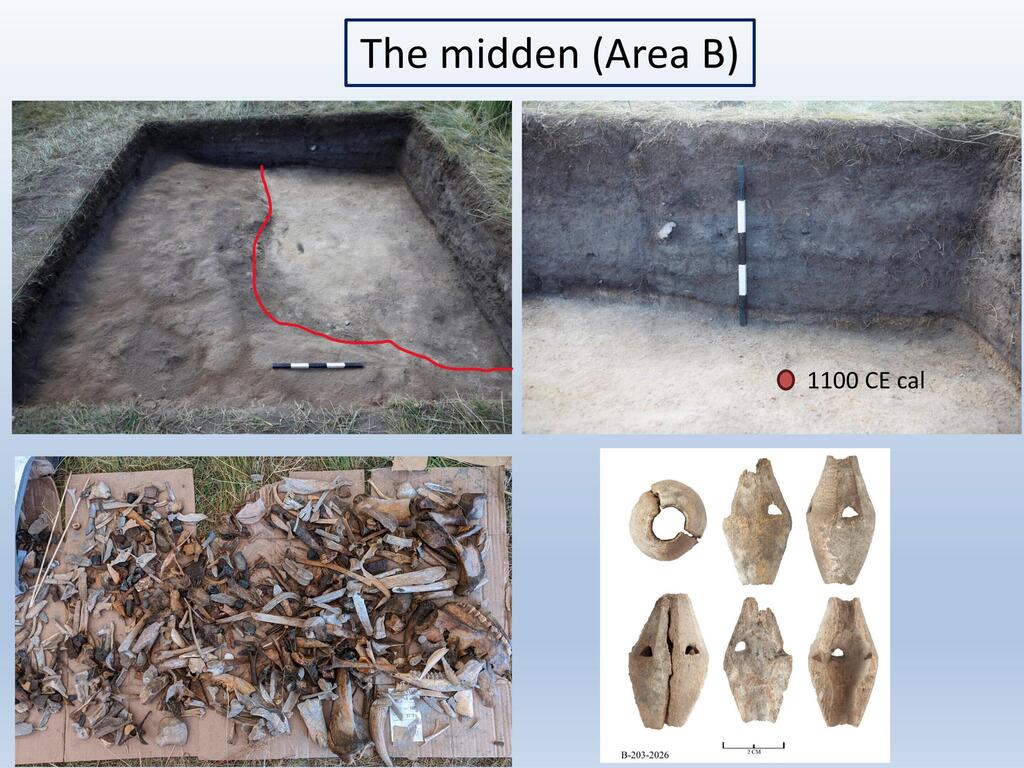

The remains uncovered—over 7,000 animal bones, many in exceptional condition—paint a vivid portrait of life along the empire's frontier: not just soldiers, but likely their families and support staff, who raised livestock, hunted and fished while coping with harsh environmental conditions. These people, long absent from historical records, played a crucial role in the empire’s day-to-day survival.

The wall system, built by the Khitan-led Liao dynasty—semi-nomadic rulers of a vast empire—remains poorly understood, especially in terms of its function and use in what is now Mongolia and northern China. Despite its massive scale, the structure and the people who lived along it are barely mentioned in contemporary historical texts.

Dating to around 1050 CE, Site 23 provides an unusually intimate look at this neglected frontier. Animal remains include sheep, goats, horses, dogs, deer and even catfish. Burn marks and butchering traces on the bones hint at complex survival strategies.

“What we found wasn't just a military checkpoint supplied by the imperial center,” said Steiner. “It was a largely self-sufficient group—possibly soldiers, possibly civilians—raising livestock, making tools from bone, hunting, fishing and making localized decisions about slaughter and resource use in a harsh, isolated environment.”

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

The team’s analysis points to a mostly independent economy, with extensive evidence of sheep and goat herding, horse rearing, some deer and mustelid hunting and seasonal fishing.

A high number of very young animal bones—especially lambs and pups—suggest the community may have faced a climate-related crisis, such as a late spring frost, matching historical accounts of environmental stresses that plagued the Liao Empire in its later years.

5 View gallery

Aerial view to square-shaped structures in Mongolia

(Photo: Tal Rogovsky, Hebrew University)

In contrast to imperial chronicles that describe grand hunting expeditions and tribute missions, the bones of Site 23 reveal the quiet negotiations of life and death on the empire’s edge.

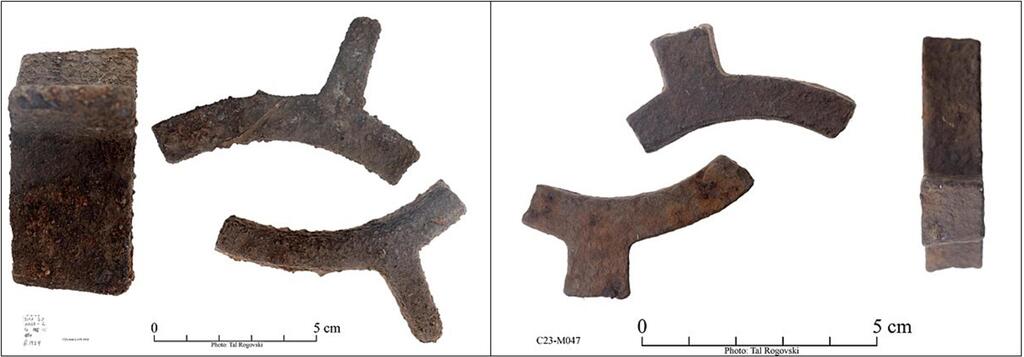

Evidence of marrow extraction from cattle bones, modified bones used as tools and ornaments and even a rare bone “whistling arrow” (a pierced arrowhead that whistled in flight) point to a resourceful and resilient population that adapted imperial policy to local reality.

“Historical texts focus on emperors, not outposts,” Prof. Rabinovich said. “But archaeology lets us hear the voices of those who lived, worked and died far from the palace.”

The study offers a significant contribution to the interdisciplinary understanding of medieval Central Asia, bridging the gap between written sources and material culture. It also provides a valuable comparative dataset for understanding frontier life in other empires—from the Roman "limes" to the Great Wall of China.