A pair of cave researchers were stunned to discover that what initially appeared to be a pile of modern garbage in a remote Mexican cave was actually sacred objects used in fertility rituals more than 500 years ago.

The cave, called Tlayócoc—meaning Badger Cave in the native Nahuatl language—is located in Mexico’s Guerrero state at an altitude of about 2,380 meters (7,800 feet) above sea level. It is known as a source of water and bat guano.

In September 2023, professional cave mapper and explorer Ekaterina Katya Pavlova and local guide Adrián Beltrán Dimas ventured into the cave—likely the first people to enter it in roughly half a millennium.

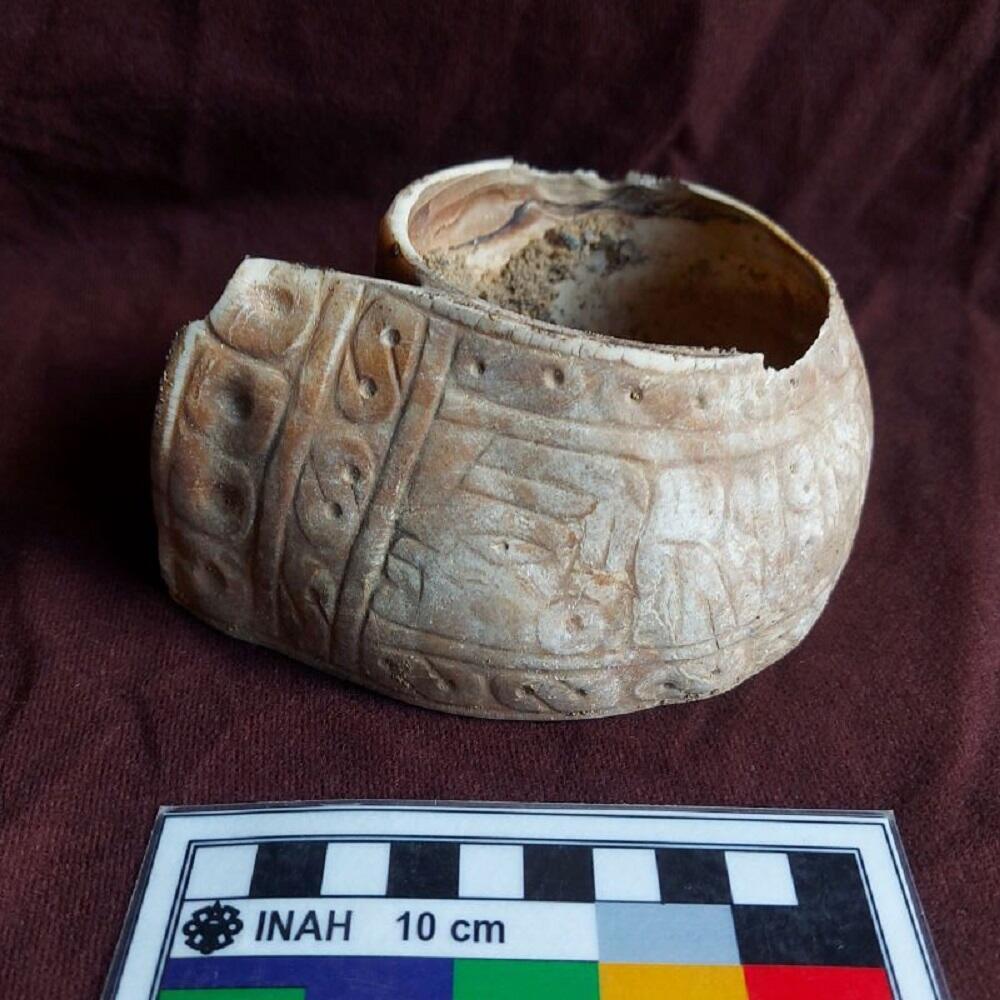

At about 150 meters in, the two explorers were forced to navigate a flooded passage, with only 15 centimeters (6 inches) of air space between the water and the cave ceiling. While pausing to look around, Pavlova and Beltrán made a startling discovery: 14 mysterious objects. Among the findings were four shell bracelets, a large and elaborately decorated sea snail shell from the Strombus family, two intact stone discs and six disc fragments, and a piece of charred wood.

The pair contacted Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), which dispatched a team of archaeologists to the site. Based on the placement of the bracelets—draped over small, rounded stalactites that archaeologists said have “phallic connotations”—researchers believe fertility rituals were likely performed in the Tlayócoc cave.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

“For pre-Hispanic cultures, caves were sacred places associated with the underworld and regarded as the womb of the Earth,” explained archaeologist Professor Miguel Pérez Negrete of INAH in an interview with Live Science.

Three of the bracelets feature engraved markings, including an “S”-shaped symbol known as the xonecuilli, which is associated with the planet Venus and timekeeping. One of the engravings appears to depict a human-like figure that may represent Quetzalcoatl, one of the most important deities in the Aztec pantheon.

Pérez dated the artifacts to the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history, between A.D. 950 and 1521, and suggested they may have been created by the lesser-known Tlacotepehua culture that once inhabited the region. “The objects were preserved thanks to the cave’s stable humidity, despite the centuries that have passed,” he said.