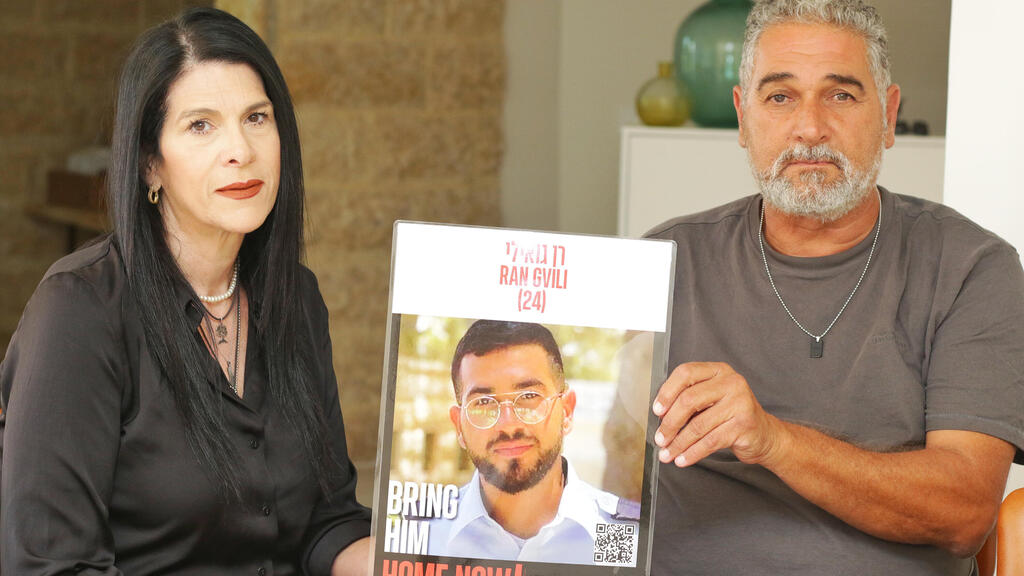

For the second time, families of hostages are marking Rosh Hashanah without their loved ones, with the parents of Ran Gvili, Bar Kupershtein, and Matan Angrest sharing the altered meaning of the holiday and their hopes for the new year.

“When everyone celebrates, we face our hardest hours,” they said. Talik and Itzik Gvili, Ran’s parents, recall a home once filled with life, large family gatherings and parties. Since Ran’s abduction, the holiday has taken on a different weight.

“We’re a big family on both sides,” Talik said. “Our home was always open, everyone felt welcome. Since October 7, we decided to keep living because Ran would want that. He was vibrant, a dancer who loved parties. Now there’s a huge void. Every day is tough but filled with hope.”

Itzik added, “Ran was the most sensitive soul—tough and strong, yet gentle. His absence is felt every moment.” Despite fears for the future, they believe military action is key to bringing hostages home. “We don’t think Hamas will negotiate. They’re inhuman.

“Maybe this operation will push them to raise a white flag,” Talik suggested, with Itzik agreeing, “Hostages could be harmed in any scenario, even without a maneuver. Their only leverage is the hostages. It’s a brutal situation.”

In January 2024, it was reported that Sergeant First Class Ran Gvili, a 24-year-old Israel Police counter-terror officer, fell in battle at Kibbutz Alumim on October 7, 2023, with his body taken to Gaza.

Yet, his parents cling to hope. “We can’t accept the report that Ran isn’t alive. We hope it’s a mistake. The odds aren’t in our favor, but we still hope he’ll return,” Talik said. Their New Year wish is simple: “That he’s alive. That he returns and laughs with us about this horrific time.”

A father’s resolve to walk again

Tal Kupershtein, Bar’s father, lost his ability to speak for years after a car accident left him bedridden, but since Bar’s abduction, he relearned to talk, driven by one goal: to voice his son’s plea. With a trembling voice and tears, he persists, awaiting the day Bar hears him.

“He hasn’t heard me speak yet. It’s important he knows I’m talking,” he said. For two years, Tal has envisioned reuniting with his son. “The first thing I’ll do is hug him. I’ll walk to him on my own legs.” Memories of Bar sustain him, like a photo of them with falafel from Tal’s pre-accident shop, which Bar managed during his hospital stay.

“We worked together for a month or two. We were very close. I volunteered with the police, taught shooting. He followed me, learned from me. I was a medic on a motorcycle and he’d help with the wounded. It fascinated him.”

Tal draws strength from Bar’s care, noting, “When my caregiver took weekends off, Bar looked after me. He was born at Wolfson Hospital, and I delivered him. He was sweet from the start, didn’t study much but always aced tests.”

This year, he and his wife Julie, who is religious, will host the holiday eve at home with Bar’s younger siblings and possibly his grandparents. “We celebrate because Julie is religious,” he explained. His New Year wish for Bar is direct: “That Bar returns.”

A holiday lost in grief

Anat and Chagai Angrest, Matan’s parents, remember vibrant holidays filled with family until two years ago. “We love having as many people as possible—nuclear family, extended relatives, anyone alone for the holiday.

Everyone’s invited, the door’s open. Matan loved the togetherness; by afternoon, we’d clear the living room, set up tables, and by evening, the house was full. People brought dishes, and Matan adored my beef roast, fish and veggies,” Anat recalled. But since that dark day, everything changed. “We’re stuck on October 7,” Chagai said.

“We have no holiday. No dates for happiness. When others celebrate, we’re at our lowest. People ask where we’ll be for the holiday, and it just highlights how much Matan is missing. Last year, we were in the square, wandering the streets. That black Saturday, Matan defended the country; since then, he’s been defending the government.”

This Rosh Hashanah eve, Anat and Chagai will spend outside their home. “As a mother, I’ll be as close as possible to the prime minister to underscore the disconnect. He could have ensured Matan was here for the holiday. How can he sit with his family while the hostages are there?” Anat said.

They sharply criticize the stalled negotiations. “Every war ends with an agreement. This is our longest war. If the prime minister wants it, Matan will be here,” Chagai emphasized, with Anat adding, “When I heard ministers say hostages can be sacrificed, I broke. He’s my son. I’ll do everything for his return.”

Their sole New Year wish is “that Matan and the other hostages return as soon as possible, ideally before Rosh Hashanah. Without them, we have no new year. May Matan not lose hope, knowing this is what the people want, giving him strength.”