The scenario in which thousands of Hezbollah terrorists would pour into northern Israel in a coordinated ground assault is no longer considered far-fetched. Long before Hamas launched its surprise October 7 attack from Gaza, the IDF was aware of Hezbollah’s detailed plans to invade the Galilee—plans that had been partially published as early as 2011 in Lebanese media. Yet on that catastrophic Saturday, Israel’s northern front was unprepared.

While the military scrambled to respond to the unprecedented Hamas assault in the south, some 2,400 fighters from Hezbollah’s elite Radwan Force and 600 terrorists from Palestinian Islamic Jihad had been standing by with full gear and designated targets in the north, waiting for the green light.

7 View gallery

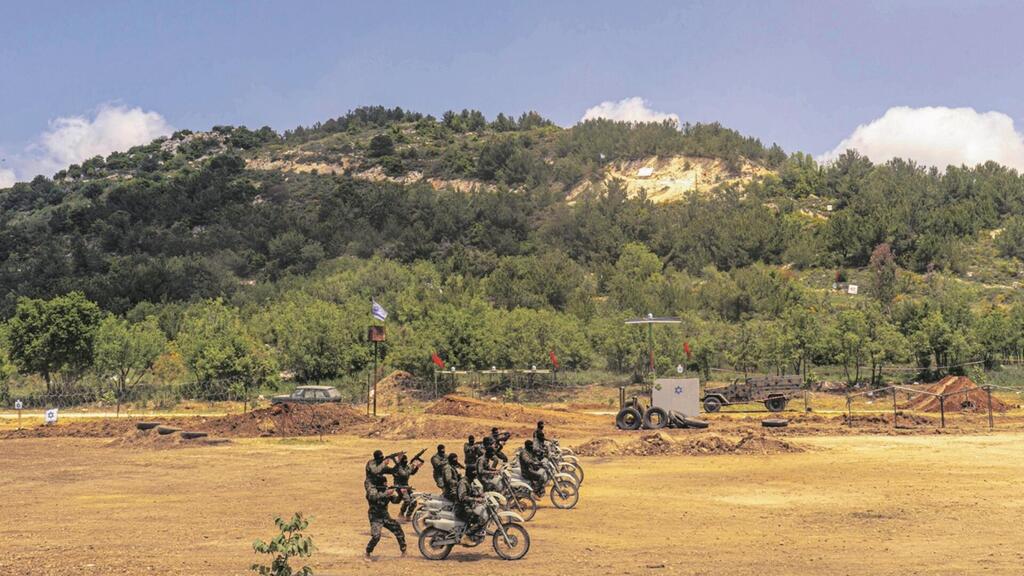

Hezbollah’s elite Radwan Force fighters drill invading northern Israel pre-October 7

(צילום: AFP)

A second wave—an estimated 5,300 additional Hezbollah fighters, both regular and reservists—was reportedly slated to follow. What may have prevented that scenario from becoming a dual-front nightmare, Israeli officials now believe, was a single phone call from Tehran.

More than two years have passed since that day, and while the Hezbollah assault never materialized, the northern front remains a source of deep concern. Unlike the widely analyzed intelligence failure in the south, the northern lapse has drawn little public scrutiny, although a surprise assault from Lebanon could have inflicted far greater damage.

No Israeli commanders were publicly held accountable for what military sources now call the “abandonment of the Galilee.” Investigations into the preparedness of Northern Command during that period under the leadership of Maj. Gen. Ori Gordin have not yet been released. “Everyone understood that if something started here, it would be a massacre,” a reserve officer told 7 Days, the weekend supplement of ynet's parent newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth. “We saw what Hezbollah had prepared. It was a miracle.”

A broader pattern of underestimation

In interviews with IDF officers, intelligence analysts and security officials conducted in recent weeks, the word “miracle” recurred—unironically. The failure to prepare came at a heavy cost: over 68,000 Israeli civilians were evacuated from northern communities, many of which remain empty today.

Hezbollah’s invasion plan, years in the making and reportedly guided by Iran, was ignored under what Israeli officials now admit was a “northern concept”—the belief that Hezbollah was deterred and that any attack would come with ample warning. Military planners wrongly assumed that limited communications infrastructure within Hezbollah would delay its ability to mobilize quickly. As in the south, the idea of a large-scale surprise assault—without prior intelligence—was not seriously considered.

But on October 7, a second front nearly opened when Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar launched the attack on Israel without coordinating with Hezbollah. Caught off guard, Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah responded with limited engagement. Had he chosen to activate the full invasion plan, Israel would have had minimal warning. Hezbollah’s weapons stockpiles—many just meters from Israeli towns along a border twice as long as Gaza’s—combined with the rugged, forested terrain, would have ensured mass casualties.

Even Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich later admitted that for hours after the Hamas attack began, the Security Cabinet was uncertain whether Hezbollah would invade as well, prompting the IDF to shift significant forces northward as a precaution.

A glimpse at what was waiting

When the IDF eventually entered southern Lebanon, it uncovered a vast network of prepared weapons caches and infrastructure. I saw Hezbollah’s readiness with my own eyes. I crossed the border nearly ten times with the IDF. In the village of Naqoura, there was hardly a house without weapons. Troops even found rockets and anti-tank missiles in a pharmacy.

The army estimates that around 85,000 weapons-related items have been seized—what officials describe as “just the tip of the iceberg.” Many of the weapons were located in residential areas, underscoring Hezbollah’s strategy of embedding assets among civilians.

Even in recent weeks, the IDF has continued locating and destroying weapons stockpiles near the border. Analysts warn that while the October 7 invasion was averted in the north, the danger has not passed, and Israel’s unpreparedness, they say, should not be forgotten.

'We got used to talking, not acting'

The IDF and former senior officers are offering sharply contrasting accounts of the military’s preparedness on Israel’s northern border ahead of the October 7 assault, with some describing a strategic blind spot that nearly resulted in a second, simultaneous invasion—this time from Hezbollah.

A senior Northern Command officer, who served before and during the war, strongly rejected allegations of prewar failures in Israel’s northern defense posture. “Contrary to the biased narrative being presented about supposed failures,” the officer told 7 Days, “the reality on the ground was very different.”

“There is no basis for talk of a ‘failure’ based on theoretical scenarios,” the officer insisted. “Before the war, the IDF built operational plans for both defense and offense based on intimate, high-quality intelligence on Hezbollah. These plans were tailored to the threat and the enemy’s capabilities, and they were rehearsed multiple times throughout 2023 and implemented successfully during combat.”

But that perspective is far from universally shared within the military. Repeated warnings about Israel’s vulnerability in the north came from Brig. Gen. (res.) Yuval Bazak, a former senior commander in the 91st Division, which is responsible for the Lebanese border.

For years, Bazak had circulated memos warning of what he described as the IDF’s “blindness” to the threat posed by Hezbollah. On October 7, he rushed to the 91st Division’s headquarters in Biranit, fully aware that if Hezbollah joined the war, his chances of survival were slim. Meanwhile, his son Guy was fighting Hamas special forces in southern Israel and was killed in action that day.

“There were IDF plans, yes,” Bazak acknowledged. “But not one of them was prepared for a surprise attack, just like in the south. And the situation in the north was even worse.”

According to Bazak, the military’s biggest mistake was its belief that it would have advance warning if Hezbollah, not Hamas, launched an attack. “But when an enemy wants to launch a surprise attack, there’s always a chance they’ll succeed,” he said. “History shows that again and again. What made the northern front even more dangerous was that Hezbollah, based on its positions along the border, didn’t need any real preparation to strike.”

Bazak claims that the military intelligence division, Aman, had committed to providing early warning ahead of any assault, just as it had done in 1973 before the Yom Kippur War. “In practice,” he said, “if there had been intelligence suggesting Hezbollah was about to attack, it would have been treated exactly like the warnings before October 7 in the south.”

Just one month before the Hamas attack, Northern Command held a special seminar titled “Preparing for War.” At the time, Hezbollah had already tested Israel’s patience with a series of provocations: an IED attack at the Megiddo Junction, the construction of outposts in Mount Dov and an alleged assassination attempt on former IDF chief of staff Moshe “Bogie” Ya’alon. Israel took no action in response, explaining that “Hezbollah is deterred.”

That was the prevailing sentiment at the seminar. Only a few voices raised concern. One of them was Col. Uri Daube, then commander of the 300th Brigade and now a brigadier general serving as chief of staff of Northern Command. He warned that if Hezbollah launched an invasion, it would break through all Israeli defense lines. Officers present at the seminar later told 7 Days that no one in the room was alarmed by his remarks or supported his call for a revised response plan.

Just months earlier, Military Intelligence chief Maj. Gen. Aharon Haliva had dismissed similar concerns from Galilee Division Commander Brig. Gen. Shai Kalper. Haliva reportedly responded, “If there’s no warning, the entire General Staff can resign.”

Lt. Col. (res.) Benjamin “Benny” Meir, who attended the seminar, said the military had fallen into a culture of complacency and avoidance.

Meir, a former head of home front defense in the 91st Division and a former special operations commander, described a command environment that “became calloused.” “We, as commanders, got used to saying things and not doing them,” he said. “If you see you can’t make an impact, either lie down on the fence and don’t move, or resign. The problem was that brigade and division commanders were operating under a mindset that said, ‘It won’t happen on your watch.’ They just kept passing the bluff along.”

A current officer in the 91st Division recalled his reaction after attending that seminar. “I left very shaken and told a colleague from command that we were screwed, that it looked very bad. The thinking was that there was no way we could handle what was waiting for us if Hezbollah acted, and therefore we had to do everything possible to avoid escalation.”

Warnings unheeded

Three months before the war, the State Comptroller’s Office was finalizing a critical audit. Comptroller Matanyahu Englman warned Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, then-defense minister Yoav Gallant and then-IDF chief Herzi Halevi about serious deficiencies in combat readiness and equipment at Lebanese border outposts. In a classified section of the report, Englman also criticized a lack of intelligence — yet this alarm went largely unaddressed.

Many in the military blame the government for restricting action against provocations such as the Hezbollah outposts on Mount Dov. But Meir countered that some responses did not require political approval.

“To remove a tent on Mount Dov,” he said, “you don’t need the political level. That’s an incident that ends at battalion or brigade command. But when you, as Northern Command commander and as a battalion commander, weaken and suppress and cause the timid to be up front, those battalion and brigade commanders won’t take initiative — they wait for someone from above to come and solve the problem.”

Thin forces, exposed towns

Against the manpower Hezbollah could have deployed, just four battalions were stationed along the northern border. That amounted to roughly 3,500 troops covering 130 kilometers (about 80 miles) of rugged terrain, compared with 59 kilometers (37 miles) of relatively flat border with Gaza. In practice, many of those troops were absent on Oct. 7 due to holiday leave.

Local alert squads — meant to hold the line until reinforcements arrived — faced additional handicaps. Unlike in the south, only a few northern towns had local access to weapons; due to a wave of thefts, many arms had been transferred back to brigade bases.

It is unclear how thoroughly these issues were examined after the war. Bazak, a member of a team led by Maj. Gen. (res.) Sami Turgeman that reviewed the IDF’s post‑Oct. 7 investigations, said his committee found that the official probes “hardly touched on the north — apart from saying we were ready in the north and not ready in the south, which is nonsense.”

Bazak argued that serious mistakes in the north require in‑depth scrutiny: “These problems are not symptomatic, they are deep, and the army has been dragging them along for many years. If it doesn’t look at them closely and fix them, they won’t be resolved. If you want to prepare for a war that will happen, you need to learn from the processes and errors you made, ask why you made them and how to make sure they don’t happen again.”

IDF response

“The pre‑October 7 policy on the Lebanon border was investigated professionally and rigorously. The operational and defensive concept on the border has been completely and dramatically changed. On October 7 the IDF failed in the south, and out of that failure—alongside the commitment to protect the country’s citizens—after‑action reviews were conducted across all theaters of operations that led to deep changes in the IDF. Today the IDF operates with an offensive, initiative‑driven approach to pre‑empt and disrupt enemy capabilities as they are forming, rather than trying to understand their intentions. The effort to analyze and learn lessons continues.

“Today the number of forces defending the northern border has more than doubled compared with the past, a new brigade has been added on the border, IDF forces operate in five fortified positions inside Lebanon, and additional outposts have been built along the border that reflect the approach of defending in front of the residents. In addition, more defensive components have been added along the border and in northern communities to increase observation, intelligence collection and strike capabilities that improve overall defense.

“In the field of home front defense there has been a substantive change and defensive elements in communities have been significantly expanded. Quick‑reaction squads were reorganized into local defense teams and the number of personnel in these teams in each community was increased, dozens of residents received improved weapons and combat equipment, resources for the defense teams and their readiness were expanded, the number of drills and exercises was doubled and new units were established with the purpose of defending the residents of the north.”