Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on Tuesday reiterated his opposition to a nuclear-armed Iran, saying that while a diplomatic agreement is possible, “it must be a Libya-style deal.” His remarks come ahead of renewed talks between the U.S. and the Islamic Republic.

The “Libya model” refers to the 2003 disarmament agreement brokered between Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi and Western powers. In a surprise joint announcement that December, then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair and U.S. President George W. Bush revealed that Libya would dismantle all its weapons of mass destruction.

Netanyahu's statement in the U.S.

(Video: Roie Avraham/GPO)

Blair called it a “historic and brave” move that would allow Libya to rejoin the international community. Bush added, in a veiled message to Iran and North Korea, that “leaders who abandon weapons of mass destruction will find an open path to better relations with the U.S. and its allies.”

Gaddafi described his decision as “wise and courageous,” saying Libya aimed to lead the creation of a world free of weapons of mass destruction and terrorism.

At the time, Libya was one of the world’s most isolated regimes. Gaddafi’s announcement that he would unilaterally abandon all efforts to develop nuclear, chemical and biological weapons stunned the global community.

Since taking power in 1969, Gaddafi had pursued covert nuclear development, aided by countries like Pakistan and North Korea. Libya’s program included the purchase of uranium enrichment centrifuges, raw materials, technical know-how and infrastructure. While it had yet to achieve a viable nuclear capability, the West viewed its progress with growing concern.

The disarmament deal followed months of secret negotiations with the U.S. and UK, supported by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The broader global context was crucial: following the September 11 attacks and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, American military threats were perceived as more credible than ever.

3 View gallery

Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Muammar Gaddafi

(Photo: Moti Kimchi, Alex Kolomoisky, Yoav Dudkevitch, Sodel Vladyslav, Shutterstock, Amit Shabi, AFP)

Senior Bush administration officials later said Gaddafi was motivated by a desire to avoid becoming Washington’s next target.

Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv

As part of the agreement, Libya pledged full transparency, allowed unrestricted international inspections and committed to destroying all materials and equipment related to weapons of mass destruction.

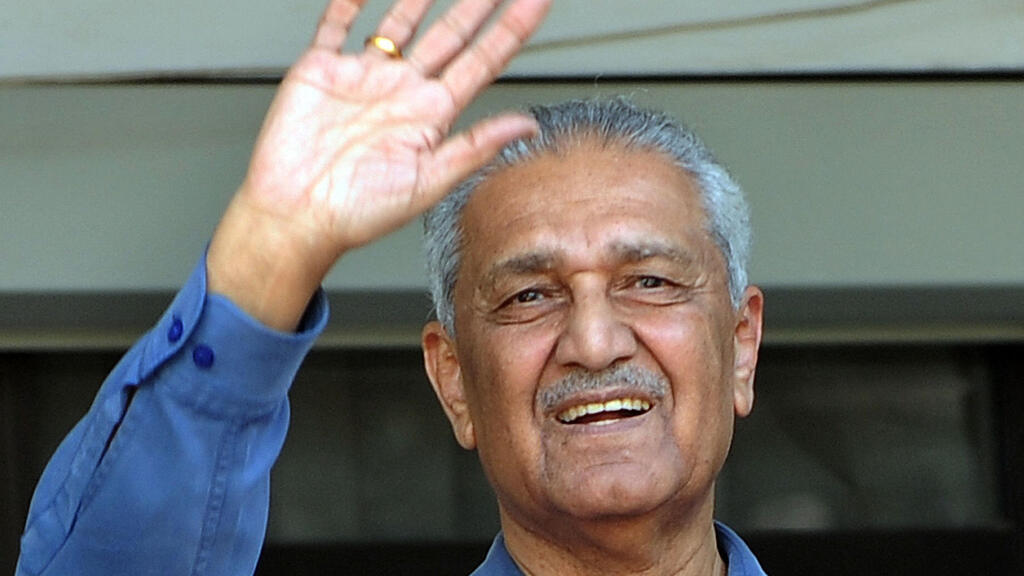

In return, the U.S. and UK promised to restore Libya’s international standing, lift sanctions, normalize relations with the West and grant renewed access to the global economy. Libya also provided intelligence on the nuclear black market led by Abdul Qadeer Khan, the Pakistani scientist known as the “father of the Pakistani bomb,” aiding efforts to curb nuclear proliferation worldwide.

In the years that followed, Libya saw an influx of Western investment in its oil sector and visits from European leaders. Gaddafi even addressed the UN General Assembly. Yet despite these developments, his regime remained politically isolated.

The outbreak of Libya’s civil war in 2011 — and NATO’s military intervention — revived questions about whether Gaddafi’s disarmament had ultimately weakened his regime.

For Iran and North Korea, Libya’s fate became a cautionary tale. Both regimes interpreted NATO’s support for the Libyan rebels as proof that relinquishing nuclear ambitions could lead to regime collapse. Iranian officials later cited the Libyan example as a reason not to abandon their nuclear program.

Iran now refers to its nuclear ambitions as a “security guarantee,” and comparisons to Libya are hard to ignore. Like Libya, Iran has been accused — and later admitted — to conducting secret nuclear development in violation of international commitments.

Both nations were linked to the A.Q. Khan network and relied on similar P-1 centrifuge technology. And in both cases, U.S. and allied leaders issued warnings — sometimes overt, sometimes implied — of military consequences if development continued.

However, analysts point out key differences. Gaddafi was a pragmatic dictator whose ideology, outlined in his “Green Book,” was secular and did not call for the destruction of other states. Iran’s leadership, by contrast, is a Shiite theocracy with a deeply ideological worldview that includes open hostility toward Israel and the West.

This fundamental difference makes Iran less likely to engage in a purely strategic compromise, as its nuclear ambitions are tied to core ideological values.

In 2003, Libya was isolated and lacked strong regional alliances. Iran today is a regional power with influence in Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen and Syria. Any significant nuclear concession by Tehran would require a broader recalibration of regional influence and power dynamics — not just a narrow arms-control agreement.

As a result, experts say the chances of Iran agreeing to a unilateral disarmament deal akin to Libya’s are extremely slim. For any deal to be viable, it would likely need to include immediate economic relief and robust international guarantees — assurances that Iran would not meet the same fate as Gaddafi’s Libya.