Nelly Prezma, 99, from Kibbutz Dorot, light a torch on the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day during a ceremony marking 80 years since the liberation of the Theresienstadt Ghetto. This year, her testimony — usually part of her lectures — included a new chapter about October 7.

She recounted how she survived Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, how she made aliyah to Israel after losing her entire family, settled in a kibbutz in the Negev and built a life believing in a better future — until reality struck again. Just as she survived the Holocaust, she narrowly escaped Hamas terrorists on October 7, who stopped near the kibbutz fence but did not reach her home.

"I couldn't believe it was happening again. I survived by a miracle twice," she said. "There is no difference between Hamas and the Nazis — the result and the evil are the same."

Although mentally sharp, Prezma's hearing has deteriorated and she did not wake when the kibbutz sirens warned of rocket fire and infiltrations. Even if she had heard them, she would not have had much to do.

Dorot does not qualify for fortified shelters, located 200 meters (656 feet) outside the designated protection zone and her home has no safe room — only external shelters, which are difficult for her to reach at her age.

Prezma recounts her story in detail, clearly practiced in telling it. During our meeting, she set the agenda: "Let's start with October 7," she quickly declared.

"A friend from the kibbutz called me and said, ‘Get up, there's a war, terrorists are invading. They've entered the neighboring kibbutzim, killing, burning, kidnapping people to Gaza, some murdered on the way," she recalled.

"Suddenly, I realized these people are me. Everything I went through is happening again. We were lucky they didn’t reach our kibbutz, but I know dear people who were killed — a kibbutz member was shot while trying to retrieve his dog from Nir Am and the parents of a friend were murdered in their kibbutz."

When did you evacuate?

"We waited until the roads were safer and evacuated on October 8. The kibbutz moved to Kibbutz Ramat Rachel near Jerusalem, but I preferred to stay with my husband’s sister in Ma’agan Michael, along with my caregiver. We stayed there for a few months until they said it was safe to return. Honestly, it wasn’t as hard as I expected to leave home at my age."

Is comparing the Holocaust to the October 7 massacre a stretch?

"Look, in both cases, they wanted to wipe us out because we're Jews. The difference is that during the Holocaust, no one helped us or fought for us. Here, even though the army delayed, it eventually came — and that's why the terrorists didn’t reach our kibbutz."

Prezma wears a pendant symbolizing the hostages, though she says she needs no reminder. "There’s no day or night when I don't think about them. It’s inside me every second," she said. "On one hand, I have no right to speak because I survived by miracles. On the other hand, as a Holocaust survivor, I understand their suffering.

“At least we had day and night. They’re underground, not knowing morning from evening. It pains me that the government is asleep — and worse, that it’s willing to sacrifice lives to stay in power. There's a choice here between the chair and life and they choose the chair. It makes me furious."

"I'll tell you something and I don’t care what people say: I wish every person blocking a hostage deal would spend one or two months in a tunnel, tied up, without food or water, with a gun to their head. Let’s see them talk the same way after that."

‘They put ears and a tail on my father’

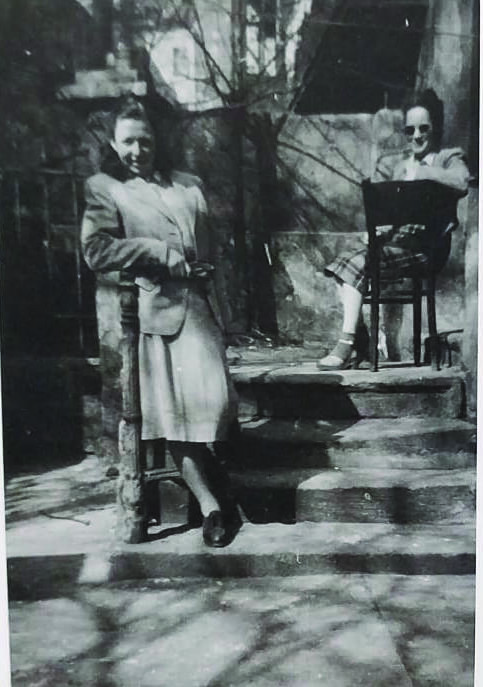

Prezma, a grandmother of six and great-grandmother of 11, ran the kibbutz dental clinic for decades, retiring at 90. She was born in Pcov, a small town in central Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), where most residents grew potatoes.

She always knew she was Jewish, but her Jewish identity was not particularly emphasized. Her father, Nathan Gutman, was the town rabbi and best friends with the local priest. Together, they led the community of 3,000 residents.

<< Get the Ynetnews app on your smartphone: Google Play: https://bit.ly/4eJ37pE | Apple App Store: https://bit.ly/3ZL7iNv >>

When the Nazis rose to power, news began filtering into town about the fate of Jews in Germany. "At first, we didn't take it seriously. People said an enlightened nation like the Germans couldn't possibly do such things," she recalled.

One day, a Jewish couple fleeing Germany arrived and asked for refuge. Prezma’s mother took them in, but after several months, townspeople pressured them to evict the couple. Since the Gutmans lived in the community’s house and her father was a public figure, her mother had no choice but to comply.

In 1939, when the Germans occupied Prague, 13-year-old Prezma had just started high school. Soon, a decree expelled all Jewish students. "We were shocked but there was nothing we could do," she said.

Further restrictions followed: Jews were banned from many stores, signs on shop doors read, "No entrance for dogs and Jews," and they faced curfews after 8 p.m. Jews were also forbidden to keep pets — Prezma had to give up her beloved cat.

"Before the war, if a student didn’t greet a teacher on the street, he was punished," she said. "After we were expelled, I once saw my teacher on the street. I didn’t know if I should greet her — it could endanger us both. As I hesitated, she approached and greeted me first. I still get emotional thinking about it."

When did the Germans come to your town?

"About a year after I was expelled from school. Two German officers came to our house and demanded that my father hand over Jews in exchange for an exemption from the curfew. He refused and from then on, they began to torture him."

They humiliated him publicly — forcing him to pull a cart, dressed with fake ears and a tail, carrying the local factory owner around the town square. "It was a show for the soldiers but the townspeople hated it. They closed their shutters and refused to watch," Prezma said.

At other times, her father was forced to clean the streets with his bare hands. Meanwhile, the women, including Prezma, were sent to nearby villages to manually dismantle Jewish-owned factories.

With no income, the family struggled to survive. Her mother foraged for berries and mushrooms to sell at the market. When that wasn’t enough, she tried to sell Prezma’s doll. "At first, I cried and refused — I was very attached to it. But eventually I understood — we were starving."

‘We said we would only leave Auschwitz through the chimney’

In 1942, the Jews of Prezma’s town were deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. "There were no beds. We slept on straw during a harsh winter. We wore everything we could fit into a single suitcase, and it wasn’t enough," she said.

Hunger was the greatest hardship: water for breakfast, a single potato for lunch and a slice of bread at night. Prezma’s mother, a trained nurse, worked in the ghetto infirmary but could do little without medicine.

Other women were forced into labor, and children, including those whose parents had already been murdered, were placed in daycare centers where Prezma worked. "We tried to lift their spirits as much as we could, organizing plays and Jewish holiday celebrations. I remember how we smuggled candles to light for Hanukkah."

Prezma’s older sister, Rosa, lived in Prague with her husband. After he was sent to a labor camp in Lodz, the family urged Rosa to join them in Theresienstadt but she stayed behind. When the ghetto evacuations began, the family learned Rosa had been deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Wanting to be together, they requested transfer.

The journey was brutal — packed into cattle cars for days without food, water, or toilets, only a bucket in the corner. Upon arrival, they learned Rosa had already been killed in a punitive transport to the gas chambers, a Nazi revenge after the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich.

Shortly after, Prezma’s father died. "He was old and sick — he simply couldn’t survive anymore," she said.

What do you remember from Auschwitz?

“I was in a group that had to fill a giant container with heavy stones, push it along a rail for a long distance, dump the stones out, then refill it and go back. A band accompanied us along the way, and of course, if someone collapsed, they were shot.

“Later, I was transferred to the kitchen, where I had to serve dirty water in the mornings and thin soup in the afternoons. After the soup ran out, a small layer of fat remained on the pot walls. They let me scrape it off and I gave it to my mother to keep her going — she was very weak.”

“They told us that every transport of Jews stayed in the camp for six months, after which they were sent to the gas chambers. One day, I ran into a close friend who had arrived there three months before me. After I had been there for three months, it was her turn,” she recounted.

“I saw her the morning she was meant to be sent to her death, saw the fear in her eyes and didn’t know what to say or how to comfort her. I just passed her by without saying a word, and I regret it to this day. I clearly remember that night. We heard their screams all night until everything went quiet and then we started to smell the burning bodies.”

“We had dark humor — kept joking that the only way out of here was through the chimney,” she said, laughing.

And yet, here you are with me. How did that happen?

“I managed to leave Auschwitz before the six months were up. There was a German man there who had been accused of murder. He wasn’t Jewish and wasn’t antisemitic, but was sent to Auschwitz as punishment and appointed to oversee us.

“He fell in love with one of our girls and wanted to save her. He went to his superiors and said, ‘There are strong women here who can work. There’s nothing for them to do here — maybe they’d be useful outside.’ That’s how he got hundreds of women out of the camp.

We had to strip completely so Dr. [Josef] Mengele could approve us. My mother’s hair was already gray, so he didn’t let her join us. That was the last time I saw her.”

Where were you sent?

“We were sent to Hamburg. The Allied bombings had already begun and we had to clear the rubble. Many girls were killed in those bombings. At some point, Hamburg was destroyed and those of us who survived were sent to Bergen-Belsen.

“Of course, the prisoners there didn’t exactly welcome us — they knew they’d have to share the little food they got with us. We were filthy, neglected, covered in boils, looked like ghosts. I was completely indifferent to what was happening around me — my mind was blank.

“There were times I told myself, ‘That’s it. I give up. I can’t go on.’ But there was always some voice in me that said, ‘I won’t give them that pleasure. If they don’t kill me, I’m going to keep going.’”

How were you finally freed?

“At some point, the Germans left and our guards were Hungarian collaborators. Then one day, a jeep appeared with a white star on it and suddenly over the loudspeaker we heard an angelic voice with a British accent: ‘Attention, attention — from this moment you are no longer prisoners. You are free.’

British soldiers had liberated us and we saw them as angels. Only when I arrived in Israel did I learn that I was supposed to hate them because they were the enemy and the occupiers.”

‘I built a proud family. That’s the true victory.’

After being freed from Bergen-Belsen, Nelly Prezma made her way to Prague, where she stayed briefly with a relative. She later studied dental technology while living in a dorm. After finishing her studies, the State of Israel was established in 1948 and she requested permission to immigrate.

But the Czechoslovakian authorities refused to issue her a passport, as her medical-related profession was considered vital. “In the end, I left with a fake identity. I had friends at the Israeli embassy in Prague and they gave me papers belonging to another girl,” she said.

“On the train, someone from Terezin recognized me and called out but I told her she was mistaken. Only after we crossed the border did I go up to her, admit that I was Nelly and explain what had happened.”

Her excitement and anticipation about reaching the Jewish homeland quickly turned into disappointment upon arrival. “Not only did no one welcome or help us — they judged us. They asked, ‘How did you walk like sheep to the slaughter and not resist?’ What a bizarre question. It’s like asking the hostages in Gaza why they didn’t resist. How can you resist when there’s a gun pointed at you?”

She ended up at Kibbutz Dorot, following friends from Czechoslovakia who had arrived before her. They visited her at the Sha’ar HaAliyah transit camp and invited her to join them.

“At the kibbutz, a young man named Zvi Prezma came up to me — he had immigrated from Latvia just before the war. He worked in immigrant absorption and came to meet the two girls from Prague, because on his list were two names: my real name and the fake identity. We always joked that he was the only man in the kibbutz who married two women.”

Nelly and Zvi, who passed away from illness about 40 years ago, had two sons: Ilan, who died 20 years ago of a sudden heart attack at age 60 and Elisha, 78, a kibbutz member who worked all his life at the kibbutz faucet factory. She also adopted Motti Shabat, who arrived as a boarding school child and still lives in the kibbutz with his three children.

“I built a proud family and that’s my true victory — over the Nazis and over Hamas,” she said with pride. “All those who rose against us to destroy us — they failed. That’s what matters. After surviving the Holocaust and October 7, the fact is: we’re still here.”